Introduction

Major litigation regarding property rights—and involving billions of dollars—which for several years has been in the federal courts may soon be resolved. By suspending through fiat the right of landlords to evict tenants for non-payment of the rents to which they were legally entitled, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention deprived them of their private property (the income stream foregone), without compensation and without due process. It was, in fact, a “taking.” The United Sates Supreme Court has already determined this act to have been without legal basis and beyond the agency’s authority. After reviewing the facts and legal issues, this paper examines the nature and magnitude of the so-far uncompensated losses to property owners. CPAs and other professionals dealing with real estate and condemnation proceedings should be aware of these issues.

While it might seem that in deciding Alabama Association of Realtors[1] on August 26, 2021 the United States Supreme Court closed the book on issues relating to federal eviction moratoria, only one chapter was closed. The question of whether the executive branch (rather than Congress) may impose such measures was answered decisively. However, the actions that were taken have financial (and possibly constitutional) consequences not yet resolved. While they were in effect, the moratoria deprived landlords of legally contracted income streams, as a result of which the values of their properties were diminished. In effect, the federal government confiscated private property by fiat without due process and without just compensation. This is a taking by inverse condemnation.

Background

During the COVID-19 pandemic, much controversy arose over whether and to what degree the federal government had the authority to interfere with contracts by suspending renters’ obligations to pay landlords for their housing services, in effect, to unilaterally and arbitrarily renegotiate their leases. The legality of Congressional actions, such as the CARES Act, [2] passed in early 2020 was not at issue. However, subsequent, similar policies issued by federal Executive branch agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) were not grounded in legislation.

The economic justification for this policy was that renter-residents who were prohibited from working (“locked down”) could not be expected to meet their rent obligations out of non-existent income. At the same time, however, programs such as the Paycheck Protection Program (established by the CARES Act and paid through employers), Emergency Rental Assistance programs[3] (paid through state, local, territorial and tribal governments) and Economic Impact Payments[4] (paid to individuals) were intended to supplement renters’ incomes and, presumably, their capacities to pay.

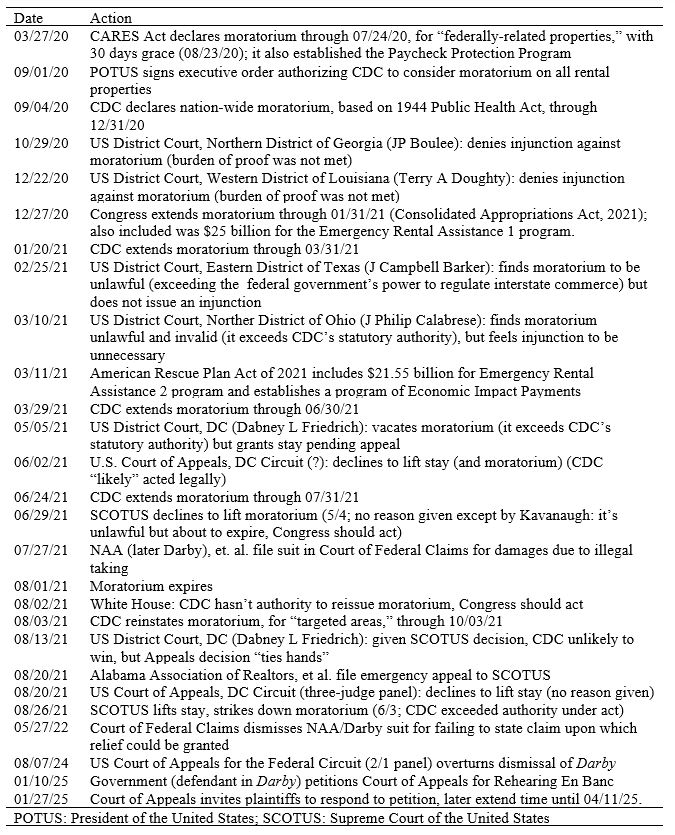

The legal justification for the moratorium was Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act of 1944[5], which authorizes such actions as “inspection, fumigation, disinfection, sanitation, pest extermination, and destruction of animals or articles believed to be sources of infection.” Notably, it does not preclude state, local, territorial or tribal authorities from imposing their own (possibly more restrictive) requirements. In the end, the United States Supreme Court struck down the moratorium, finding that the CDC had exceeded its authority under the act. In order to reduce confusion due to the multiplicity of legal and legislative actors, actions, venues and details involved, Table 1 provides a simplified chronology.

Table 1. Selected Chronology

Federal Protection for Renters

Under authority of Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued an order prohibiting landlords in the United States from evicting tenants for non-payment of rent, effective September 4, 2020 through (as extended) June 30, 2021.[6] In order to qualify, tenants had to meet certain requirements concerning housing and income (all applicable). They were required to declare, under penalty of perjury, that they:

- had used their best efforts to obtain government assistance for housing,

- (i) expected to earn no more than $99,000 ($198,000 jointly) during 2020, or (ii) were not required to report any income in 2019, or (iii) received an Economic Impact Payment (stimulus check),

- were unable to pay their full rent due to a substantial loss of income or extraordinary out-of-pocket medical expenses,

- were making their best efforts to make timely partial payments of rent, and

- if evicted, would likely become homeless or have to move into a shared living setting.

The CDC’s moratorium was, in some respects, more far-reaching than the original CARES version:[7] It:

- applied to all residential properties nationwide, and not just to those participating in federal financing programs,

- included criminal penalties for violators, and

- allowed landlords to charge “fees, penalties and interest” for non-payment (but, of course, did not allow them to enforce collection through eviction).

In late December, 2020, the Consolidated Appropriations Act in effect ratified the moratorium by extending it through the following month.[8]

Federal Protection for Landlords

The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) provided partial relief for landlords in the form of forbearance to owners of multifamily properties financed with Fannie Mae- or Freddie Mac-backed mortgages through (as extended) September 30, 2021. While the property was in forbearance, owners were required to inform tenants in writing about protections available to them during both the forbearance and repayment periods and to agree not to evict tenants solely for non-payment of rent. During the repayment period, owners also had to give tenants notice of at least 30 days to vacate, not charge late fees or penalties for non-payment of rent and allow tenants flexibility in payment of back-rent.[9]

While this policy reduced landlords’ periodic expenses, it did nothing to replace their missing income. For that, landlords could apply for the Treasury’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program. In December, 2020, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, mentioned above, appropriated $25 billion in Emergency Rental Assistance for landlords, and in March 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021appropriated another $21.55 billion. However, these funds were funneled through state and local governments, which have moved slowly.

Value

For a taking to occur, something of value must be taken. We employ one method for estimating value: the Time Value formula. While that this is a staple of the academic introductory Finance course, it is not limited to that role. It is applied every day (sometimes formally, sometimes just subliminally) by individuals and institutions, by amateurs and professionals and by consumers and investors to make millions of real-world decisions moving billions (possibly trillions) of dollars around the world. More to the point, it is employed in litigation every day by expert witnesses.

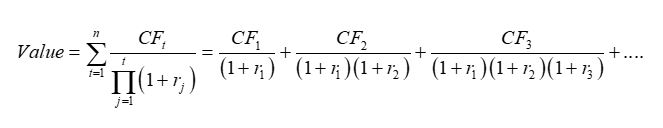

This approach views the economic or intrinsic value of an asset as the sum of the present values of all of the cash flows expected to accrue from owning it. Formally, for each unit in each property

where CFt represents the after-tax net rent expected in period t. The discount rate, rt, depends upon prevailing interest rates for loans of similar maturity and risk and can vary from period to period.

The Time Value formula is not the only method to estimate value, but is the one that can be applied most conveniently in this context. The inputs to the calculation are not merely hypothetical. The cash flows (numerators) are rents contracted by lease, which are known; the discount rates (denominators) are based on interest rates, which are observable or may be inferred from futures markets. It is also applicable quite generally. In contrast, the method of comparables is too granular for this purpose, requiring individualized data for similar properties that is less easily obtainable (and may be subject to dispute).

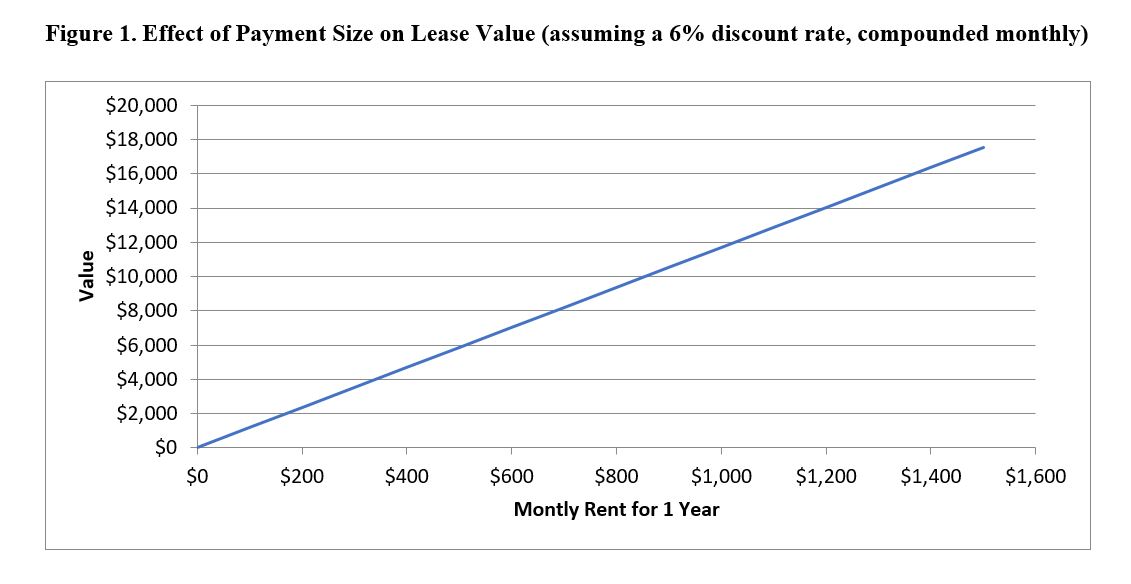

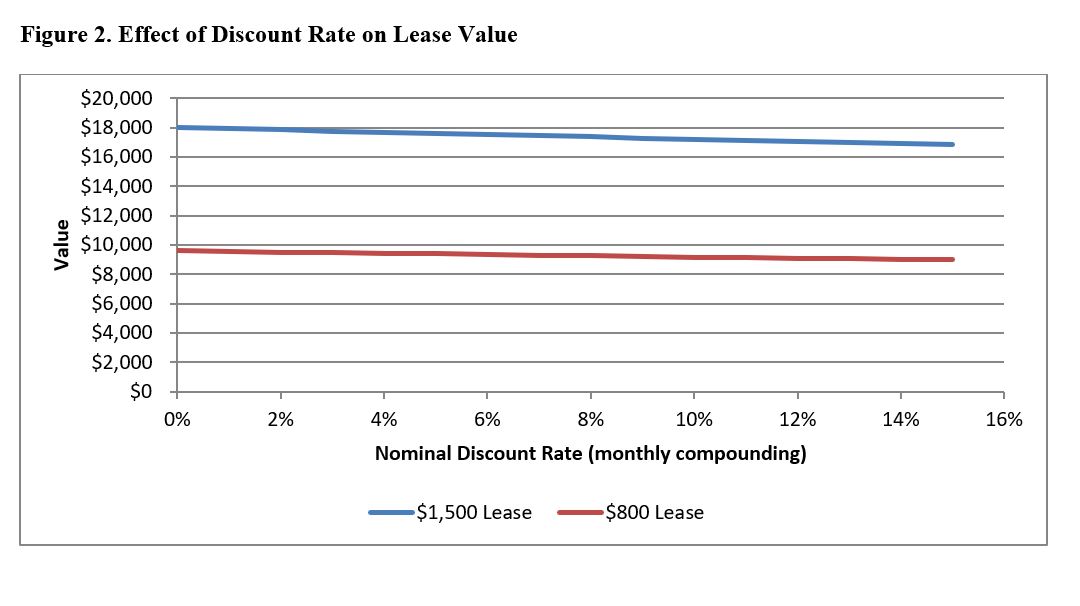

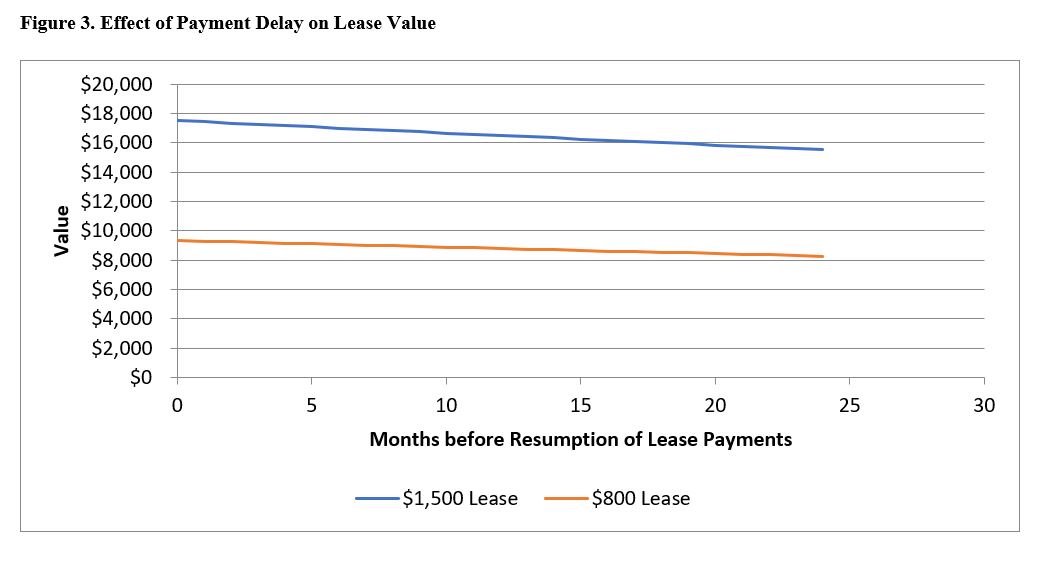

Clearly, value is directly related to the size of the expected future cash flows, CFt, and inversely related to the prevailing discount (interest) rate, rt, and the time until receipt of the expected cash flow, t. For example:

- A one-year lease paying $800 per month (one month in advance) is worth $9,341.62 when the interest rate is 6 percent per year (compounded monthly). Under the same conditions, a lease yielding $1,500 per month is worth $17,515.54. Of course, a lease that pays zero is worth nothing, beyond, possibly, its option value.

- At an interest rate of 3 percent per year (compounded monthly), the same two leases are worth $9,469.42 and $17,755.16, respectively.

- At the 6 percent interest rate, if the payment of these leases is delayed for three months, their respective values drop to $9,202.89 and $17,255.41, but to $8,798.92 and $16,497.98 if the delay stretches to one year.

The last point, regarding interest rates is particularly relevant, in two respects. First, in its long-standing effort to simultaneously support asset values and shield the U.S. Treasury from the cost of servicing its multi-trillion dollar debt by driving and holding interest rates close to zero (“Quantitative Easing”), the Federal Reserve also magnified the property owners’ potential losses and, hence, the Treasury’s potential liability. That is, by artificially depressing interest rates—and thus, artificially increasing asset values—the Fed set up anyone who invested at the then-inflated prices for a future capital loss, when rates eventually revert. Although interest rates have risen since that time (thus reducing present values), the losses had already been incurred. (By the same token, it can be argued that anyone who sold assets under these conditions enjoyed the same undeserved windfall gain as those who sold Enron shares before the facts came out.) Second, the opportunity losses of landlords might be even greater than this suggests, since—had landlords received the rents when they were due—they would have been able to invest them at the subsequent higher interest rates.

While the eviction moratorium was in effect, expected net rents dropped to zero for the expected duration of the policy. The loss in value—the size of the taking—equals the present value of the incomes forgone or delayed. In the aggregate, the taking equals the missed rent on thousands of properties multiplied by the number of months for which the rent of each was in abeyance. The total must amount to tens, if not hundreds, of billions of dollars. This represents a colossal—and unlawful—transfer of wealth from owners to renters. The Urban Institute estimated on June 24, 2021 that, with 4.2 million potential evictions during the following two months, landlords could lose $8.0–$50 billion in rent and repairs, on top of $2.6–$6.6 billion in legal expenses.[10]

Litigation

The Court of Federal Claims

The National Apartment Association filed suit on July 27, 2021 in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, claiming that more than 10 million delinquent tenants owed $57 billion in back rent by the end of 2020, and that a further $17 billion had accrued since then. The suit is “open to all rental housing providers who have been damaged.” The 38 original plaintiffs ranged from “mom-and-pop” owners of single-family homes to corporate owners of complexes with over 3,000 apartments. According to the filing, the CDC order abrogated several Constitutional rights: “the right to access the courts, the freedom to contract with others absent government interference, the right to demand compensation when property is taken by government action and the limits of federal government power.”[11]

The claims for relief in the National Apartment Association complaint involve (1) taking without compensation and (2) illegal exaction by the CDC because it exceeded and infringed upon its statutory and regulatory authority under Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act.

The “Takings” Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution is brief yet clear: “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” Privately owned rental properties are obviously private property. The just compensation is typically determined in an eminent domain hearing, before the act of taking. (It should at least resemble “fair market value.”) However, there was no such proceeding before the act and the expropriated parties never had a chance to argue their cases. Private property was simply confiscated. The matter of compensation is yet to be decided, after the act.

The Court of Claims dismissed the suit on May 17, 2022, noting that legislative relief already had been appropriated (whether or not it was actually received). The Court ruled that the CDC’s moratorium did not constitute a taking—and that the government could not be held liable—because it was not an official act, since (a) it had not been authorized explicitly by Congress and (b) the Supreme Court had subsequently vacated it. The ratification of the moratorium contained in the Consolidated Appropriations Act was simply brushed aside, as was the fact that this was all executed under color of law.

The Court also found the moratorium not to be an illegal exaction since landlords had not actually paid anything to the government, although the government had, in effect, shifted public costs to private parties. Recall that the moratorium permitted the assessment of rent, interest and penalties— but not their collection.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

This decision was appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (Appeal No. 22-1929), with oral arguments heard on September 7, 2023.[12] Regarding the $50 billion-plus appropriated for their relief, the appellants claimed that it could have compensated landlords only if they had actually received it. (The government admitted that it was still unclear whether the states had actually distributed the funds.)

The Court of Federal Claims had denied that the moratorium constituted a taking because it was not “authorized” by Congress (and was later declared to be illegal). The appellants argued that “the important distinction . . . is whether the act was undertaken by the Government (regardless of whether the act is later deemed to have been a lawful exercise of authority) or by a rogue government official . . . .” Moreover, they contended that, even if no taking had occurred, an illegal exaction had occurred, because landlords could neither collect rents nor replace non-paying tenants with paying tenants. “The Government wanted non-rent-paying tenants to be housed . . . . The costs . . . are an obligation of the Government and not the landlords.”[13]

Three organizations submitted amicus briefs: the New Civil Liberties Alliance, the National Association of Home Builders and the National Association of Realtors. All observed that the dismissal could “incentivize” or “embolden” governmental overreach, but the Realtors’ brief made the strongest argument, quoting two recent Supreme Court decisions:

- “[P]reventing [landlords] from evicting tenants who breach their leases intrudes on one of the most fundamental elements of property ownership—the right to exclude.” Alabama Association of Realtors, op. cit.

- “[A]n abrogation of the right to exclude . . . constitutes a per se physical taking.” Cedar Point Nursery.[14]

A three-judge panel of the Court on August 7, 2024, reversed the dismissal by the Court of Federal Claims and remanded the case back to it.[15] While the Appeals Court agreed that the CDC lacked authority to issue such an order, it nevertheless found the action to be “authorized for takings-claim purposes.” For this, it relied on two tests:[16]

- “[E]ven if an action by a government agent is unlawful, it will likely be deemed authorized for takings claim purposes if it was done within the normal scope of the agent’s duties—for example, if it was done ‘pursuant to the good faith implementation of a congressional act.’”

- “If instead the action was outside the normal scope of the government agent’s duties—or, despite being within that scope, it contravened an explicit prohibition or other positively expressed congressional intent—it will likely be deemed unauthorized.”

The Appeals Court found the CDC’s action to within the normal scope of its duties, since as a “national public health agency,” it may ‘make and enforce such regulations . . . necessary to prevent the . . . spread of communicable diseases . . . .’” At the same time, the Court held it to represent a good-faith implementation of the Public Health Services Act. Neither did the CDC’s order violate any explicit prohibition or congressional intent.

Finally, the Appeals Court found that the property owners had advanced a claim of a physical taking (which requires just compensation), rather than a regulatory taking. Referring explicitly to Cedar Point Nursery, the Court found that “we cannot reconcile how forcing property owners to occasionally let union organizers on their property infringes their right to exclude, while forcing them to house non-rent-paying tenants (by removing their ability to evict) would not.”[17]

At the time of writing, this issue is still unsettled. On January 10, 2025, the government filed a Petition for Rehearing En Banc. On January 27, 2025, the Appeals Court invited the property owners to respond to the Petition; on February 4, 2025, the Court extended the time for their response until April 11, 2025.

Darby Development et. al. seem not to be the only parties seeking compensation for a taking. On January 8, 2025, Rebecca Shaffer, a small landlord in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania also filed suit in the Court of Federal Claims.[18] She claims that for ten months she was unable to evict a non-paying tenant and is seeking reimbursement for lost rental income, compensation of any damage to her property, as well as legal fees and related costs. An answer is due by March 10, 2025.

Conclusion

The question of whether “forced forbearance” and related policies actually benefited the public on net may never be settled to broad satisfaction. In any case, it is still too early to draw conclusions regarding one element of the private costs: while the Supreme Court has settled the legality of the administrative moratoria, the landlords’ and owners’ suits have yet to run their courses. Nevertheless, private property was taken arbitrarily, so far as can be observed, without either due process or compensation.

References

42 CFR 70.2, Measures in the event of inadequate local control. Available at https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-42/chapter-I/subchapter-F/part-70/section-70.2

Batko, S. and Rogin, A., “The End of the National Eviction Moratorium will be Costly for everyone,” , June 24, 2021. Available at https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/end-national-eviction-moratorium-will-be-costly-everyone

Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. 116-260, 134 Stat. 2078-79 (2021). Available at https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ260/PLAW-116publ260.pdf

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, 2020. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ136/pdf/PLAW-116publ136.pdf

Federal Housing Finance Agency, FHFA Extends COVID-19 Multifamily Forbearance through September 30, 2021. Available at https://www.fhfa.gov/Media/PublicAffairs/Pages/FHFA-Extends-COVID-19-Multifamily-Forbearance-through-September-30-2021.aspx

Federal Register, Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions to Prevent the Further Spread of COVID‑19. Available at www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/04/2020-19654/temporary-halt-in-residential-evictions-to-prevent-the-further-spread-of-covid-19

National Apartment Association, “NAA Sues Federal Government to Recover Industry’s Losses under Nationwide Eviction Moratorium,” July 27, 2021. Available at https://www.naahq.org/naa-sues-federal-government-recover-industrys-losses-under-nationwide-eviction-moratorium

National Association of Realtors, Appellants’ Corrected Brief in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellants and Reversal. Available at https://fedcircuitblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/APPELANT-169-MODIFIED-ENTRY-CORRECTED-OPENING-BRIEF-1.pdf

Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. 264. Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2019-title42/pdf/USCODE-2019-title42-chap6A-subchapII-partG-sec264.pdf

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, Darby Development Company, et. al. v. United States, No. 22-1929, oral argument (mp3). Available at https://oralarguments.cafc.uscourts.gov/default.aspx?fl=22-1929_09072023.mp3

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, Darby Development Company, et. al. v. United States, No. 22-1929, opinion. Available at https://www.cafc.uscourts.gov/opinions-orders/22-1929.OPINION.8-7-2024_2363309.pdf

United States Court of Federal Claims, Darby Development Company, Inc., et. al. v. United States, No. 21-1621L (2022), CFC. Available at https://fedcircuitblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Opinion-Below-1.pdf

United States Court of Federal Claims, Shaffer v .United States, 1:25-cv-00015.

United States Supreme Court, Alabama Association of Realtors, et al. v. Department of Health and Human Services, et al., 594 U.S. ___ (2021). Available at https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/20pdf/21a23_ap6c.pdf

United States Supreme Court, Cedar Point Nursery et. al. v. Hassid et. al., 594 U. S. ____ (2021). Available at https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/20pdf/594us1r53_0pm1.pdf

United States Treasury, Economic Impact Payments. Available at https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-american-families-and-workers/economic-impact-payments

United States Treasury, Emergency Rental Assistance Program. Available at https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-state-local-and-tribal-governments/emergency-rental-assistance-program

Notes

[1] Alabama Association of Realtors, et al. v. Department of Health and Human Services, et al., 594 U.S. ___ (2021).

[2] Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, [CARES Act], 2020.

[3] U.S. Treasury, Emergency Rental Assistance Program.

[4] U.S. Treasury, Economic Impact Payments.

[5] Public Health Service Act, 42 U.S.C. 264 and 42 CFR 70.2, Measures in the event of inadequate local control.

[6] Federal Register, Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions to Prevent the Further Spread of COVID‑19.

[7] Darby Development Company, Inc., et. al. v.United States, No. 21-1621L (2022), CFC, p. 3.

[8] Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. 116-260, 134 Stat. 2078-79 (2021).

[9] Federal Housing Finance Agency, FHFA Extends COVID-19 Multifamily Forbearance through September 30, 2021.

[10] Batko, S. and Rogin, A., “The End of the National Eviction Moratorium will be Costly for everyone,” June 24, 2021.

[11] “NAA Sues Federal Government to Recover Industry’s Losses under Nationwide Eviction Moratorium,” July 27, 2021.

[12] Darby Development Company, Inc., et. al. v. United States (audio recording)

[13] Corrected Brief for Amicus Curiae National Association of Realtors, p. 3.

[14] Cedar Point Nursery et. al. v. Hassid et. al., 594 U. S. ____ (2021), Slip Opinion, p. 1.

[15] Darby Development Company, Inc. et. al., v. United States, 22-1929.Opinion.8-7-2024.

[16] Id., p.16ff.

[17] Id. P. 31.

[18] Shaffer v. United States, 1:2025-cv-00015.

@N Universe/Shutterstock.com

@N Universe/Shutterstock.com