Introduction

Amidst an ensuing cost of living crisis in many geographies, a higher for longer interest rate environment, and the sustained shocks of inflation resulting from the pandemic years and the return of interstate war in Europe, a feeling of economic insecurity pervades many societies today. Remarkably, in an economy which is expanding over 3% per annum—and with rising wages, and multi-decade low unemployment—the feeling of financial insecurity amongst Americans is at its highest level in over a decade.[1]

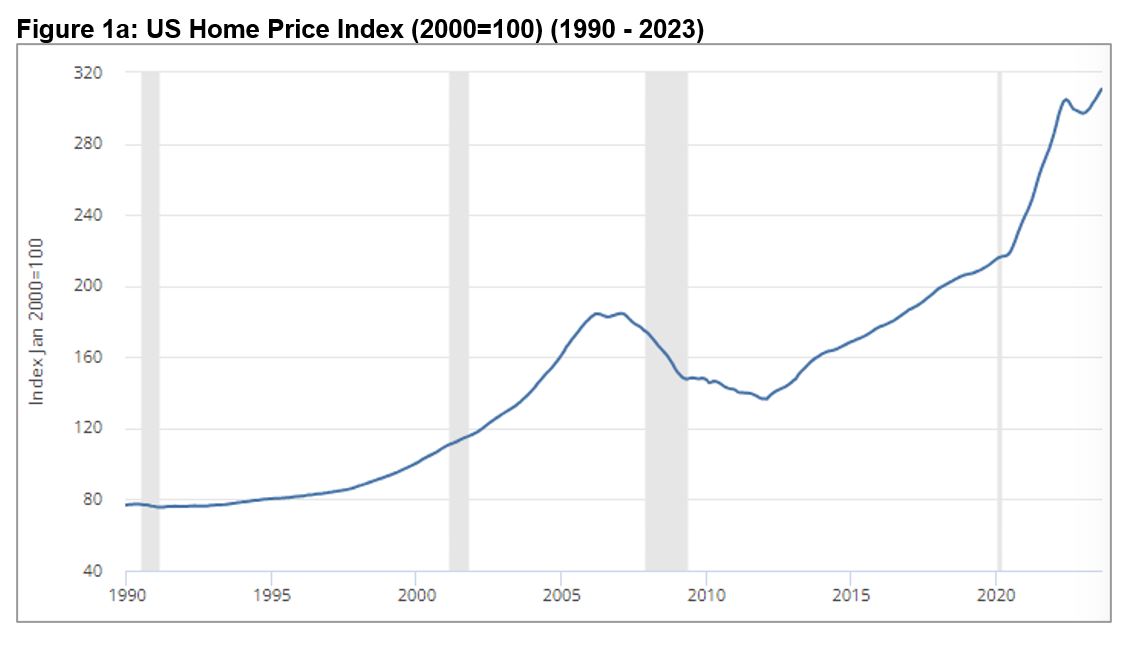

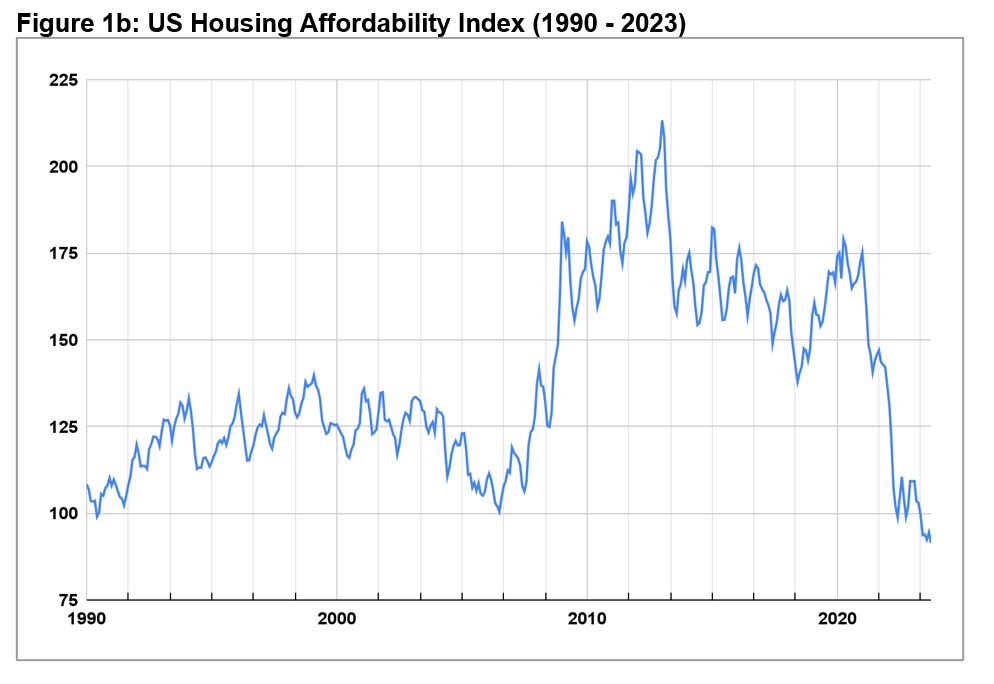

A central contributing factor to these negative ‘vibes’[2] is housing. Even despite a rapid monetary tightening cycle, house prices continue to hit historic highs—and one measure of housing affordability in the US hit a historic low in late 2023.[3] Rents continue to climb, and one recent measure posits that a record one half of renters in the US are cost burdened.[4]

Source: St. Louis Fed

Source: National Association of Realtors

Moreover, the affordability crisis is also a contributing factor to sticky inflation: over one third of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Consumer Price Index (or CPI, the Fed’s preferred measure) is weighted toward shelter costs.[1]

This problem, of course, is not unique to the US. Many advanced and emerging market / developing economies alike face a housing crisis: including Australia, France, Germany, New Zealand, Malaysia, and the Philippines.[2] In continental Europe,by one estimate, some 80 million people are cost burdened,[3] and spend more than 40% of their income on housing. And, arguably, even when prices fall in a specific market—such as a recent dip in Canada, the prolonged crisis of affordability and stubbornly high prices—can have serious knock-on effects for economic growth. Given the historical correlation between innovation and urbanization,[4] the lack of provision of affordable shelter in key gateway cities (typically areas of high demand) can have a detrimental impact on the generation of innovation—with ripple effects felt far beyond the city. And, in our increasingly services-oriented economies, the amenities which bolster the quality of life (thus enhancing metrics beyond GDP) are often dependent upon essential workers living near their jobs. In high cost jurisdictions—often the locus of demand for such amenities—this means that mixed income and affordable housing are also an essential part of urban life.

A disjointed array of policy levers—implemented as a reaction to the sharp rise in residential property prices—can also have a deleterious knock-on effect on economic growth. As we explore below, amidst our globalized capital markets landscape, foreign capital flows can often be a contributing factor to an acceleration in house prices—especially in global gateway cities. While some policy officials have introduced a variety of measures designed to restrict foreign purchases (such as implementing a a hefty stamp duty; or outright ban on foreign purchases of residential property[5]), others have resorted to restricting immigration, in the name of curbing the rise in house prices. Given the reality that many skilled immigrants may not yet have the capacity to purchase such a home, such a backlash on immigration may not only be ineffective, but, crucially, it has the potential to create a structural drag on growth—especially amidst labor shortages and aging demographics, which currently plague many advanced economies.

Looking beyond the interrelationship between housing and economic growth, it is important to point out that shelter is an essential component of the means to live a dignified life. As we explore below, some societies address this better than others: for example, in Paris, where salaried but essential workers may not have the means to live near their place of work in one of the most expensive cities in the world. Accordingly, the government and the private sector have stepped in to supplement and support housing needs for such workers, which is one method of supporting small local (and essential!) businesses.

In such a way, set against the backdrop of an elevated awareness around sustainability and impact investing, the ability to provide affordable housing for those in need (which includes workforce as well as middle income housing) constitutes a verifiable way of fulfilling the ‘S’ or social components within ESG investing. Especially in jurisdictions with forward-looking and balanced policies, private capital can thus be increasingly relied upon to be part of the solution. Although the returns on affordable housing might be more bond-like in nature (as opposed to high growth equity plays), the ability to deploy investment to address one of the most pressing social issues of our time gives investors the opportunity to be true stewards of the built environment. As such, directing capital toward affordable housing can be seen as a true form of infrastructure investment, as the provision of housing as a basic human need has the potential to support productivity—and the means to live a dignified life—thus enhancing all parts of society and economy.

- Macro and micro factors: what’s behind the sustained rise in house prices, and the prolonged crisis of affordability?

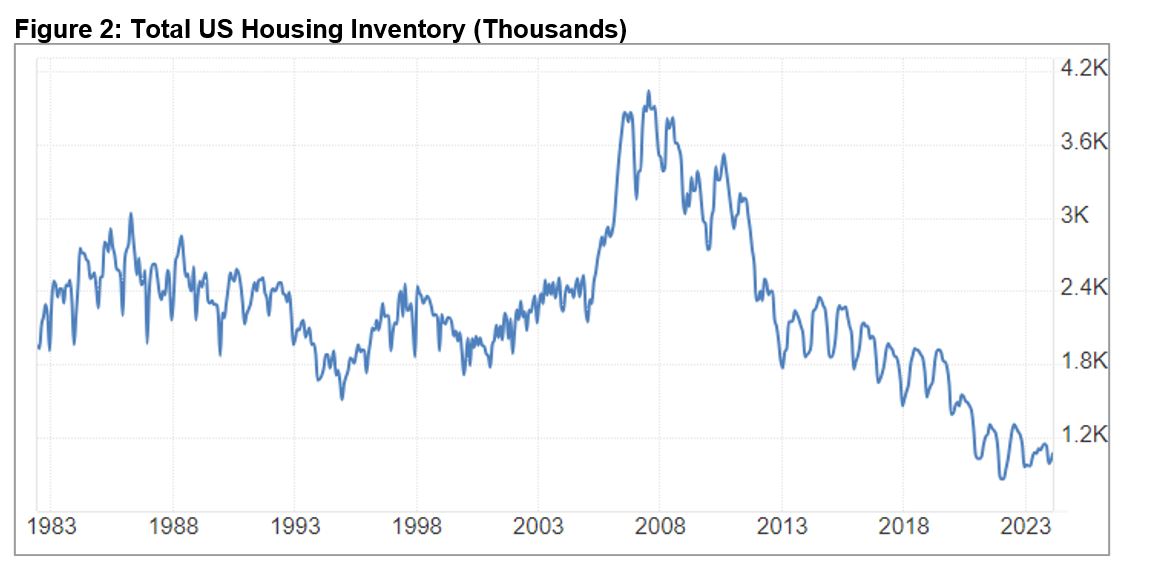

The number of factors which have contributed to a sustained crisis of affordability in the US are unlikely to vanish any time soon, even despite a time of heightened uncertainty in the interest rate, asset price, and real estate environments. Firstly, on the supply side, we’ve faced a chronic shortage of housing stock in the US since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). As we can see in Figure 2, total housing inventory in the US has reached a multi-decade low.

Source: National Association of Realtors (accessed via Trading Economics)

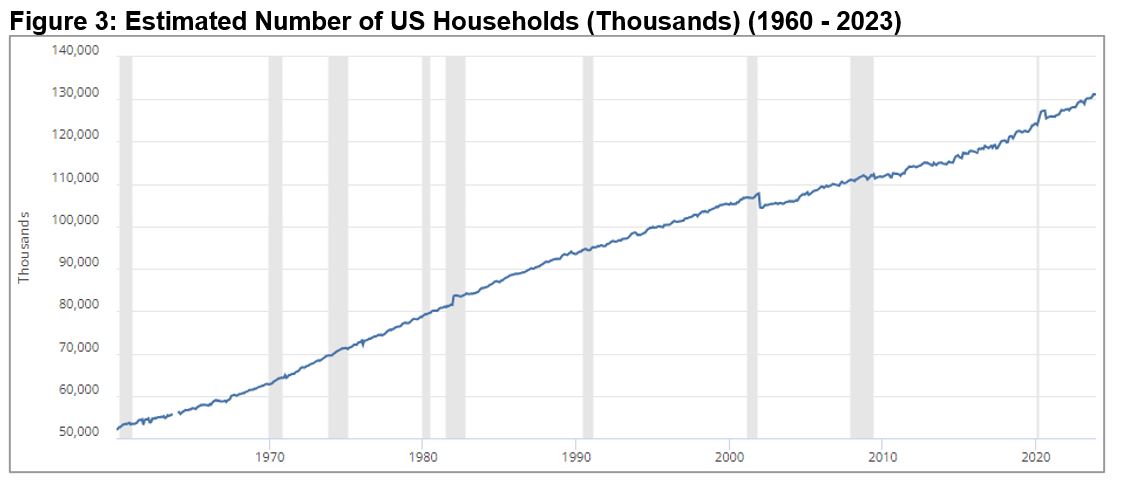

And, on the demand side, despite aging demographics, housing formation needs in America have not slowed (ref Figure 3).

Source: FRED

Partly, this is due to cultural factors: even though a growing number of retirees might opt to downsize, they still need a roof over their heads, thus resulting in perhaps smaller square footage, but often, a single home nonetheless.

More recently, amidst multiple inflation shocks, and a sharp increase in the incidence of climate-related events and natural disasters, development, operating, and insurance costs have skyrocketed. The sharp rise in insurance costs has led some investors to turn in the keys for certain properties or entire portfolios, from hotels to the (already beleaguered) office space, and from market rate multifamily rentals to affordable housing.[1] [2] Labor shortages in the construction space prior to the pandemic—and the sustained rise in wages—have further contributed to elevated operating and construction costs, both in the US and in other jurisdictions such as Canada.[3]

Monetary policy has also been a contributing factor to the affordability crisis in housing: both by stoking demand, and also by curtailing supply (although perhaps inadvertently). The low to negative interest rate policies (ZIRP and NIRP) enacted by central banks in the wake of the global financial crisis (GFC) meant that yields on traditional safe haven assets—such as government bonds—were altogether unimpressive (or indeed negative yielding). Consequently, large pools of institutional capital rotated out of fixed income assets, and into real estate as an asset class—in fact, one can argue that this shift is one of the contributing factors to the explosive growth of private credit markets in recent years. As a result, prices of residential property and rents have skyrocketed: in key markets such as Atlanta, retail investors have been a contributing factor to some of the fastest rising rents in the US, and also pushing home ownership out of reach for many[4] with the median list price for homes in Atlanta increasing by 65% between 2018 – 2023.[5]

Central bankers have also been taken to task for curtailing the supply of housing amidst a ‘higher for longer’ interest rate environment. As is the case across the real estate landscape, higher rates have crippled development, and also pushed developers into the arms of potentially riskier lenders, such as private credit.

Looking beyond monetary policy, the globalization of capital flows—tinged with geopolitical dynamics—has been another key causal factor of the crisis of affordability. Investment from Asian households into the Canadian residential market has led to frothy pricing in key gateway cities such as Vancouver and Atlanta—and indeed, at the height of the US-China trade war, many Chinese households diverted capital from the US housing market to the Canadian market, further stoking demand. And, amidst regional uncertainty, Singapore’s status as the main gateway city to Asia has meant that the city continues to magnetize flows of foreign capital into its residential property market. The rapid influx of foreign capital into both of these markets have prompted local officials to restrict foreign purchases of residential property, in efforts to manage the sharp rise in affordability.

Policy levers in the US

LIHTC

So what are some of the solutions? In the US, the main policy mechanism for affordable housing has been the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). Initiated as part of the 1986 Tax Reform, the LIHTC works by the federal government allocating a certain amount of tax credits to state governments. Authorities then award these credits to developers in an RFP process, who then might sell the credits to investors. Various reforms and amendments have been made with LIHTC over the last few decades, such as establishing a floor rate of 4% for LIHTC credits.[6]

Over the decades, the policy has provided a rare avenue in which a deeply divided political body within the US somehow manages to coalesce: indeed, despite sharp polarization, Republicans and Democrats have often come together on addressing the housing issue. Most recently, bipartisan support in the House passed new measures and proposed legislative changes for LIHTC, which could result in the development of 200,000 new affordable units over the next few years.[7] As the bill sits before a closely divided Senate (and thus might be jeopardized by entrenched debates on spending), it is important to note that regardless of the political outcome in November 2024, we can likely forecast that the provision of low to middle income housing will be one of the issues on which both parties will try to seek agreement. Thus, can also posit that as LIHTC approaches the 40 year mark, it actually remains fit for purpose, especially in light of the waves of amendments which have unlocked new supply.

At the local level: and whither office-to-resi conversions?

Looking beyond the federal and state level, where are innovative policies being implemented in cities in the US? After all, so much of housing policy comes down to an acutely local level. Often (and this is the case in many cities—even ‘progressive’ ones—across the globe) even the most seemingly efficient solutions to address the affordability crisis can fall prey to ‘NIMBYism’: that is, ‘not in my backyard.’ Indeed, in one of the most expensive cities in the world—Sydney, Australia—one researcher points to a ‘NIMBY paradox’: according to which residents decry the development of affordable housing in their neighbourhood, but then bemoan the scarcity of workers to service local amenities.[8] Thus, updates to zoning policies can often be a way of unlocking new supply in cities. New York City Mayor Eric Adams’ recent proposals to lift the FAR cap[9]—or existing floor to area ratios which determine the size of lot developments in the city—present one way of updating legislature in light of density changes in Manhattan.[10]

Another change at the local level currently piloted in New York and Chicago is the much hyped focus on office-to-resi conversions. In light of the ‘WFH’ phenomenon—and the somewhat dinosaur-like edifices of empty office buildings in central business districts (CBDs)—some forward-thinking policymakers have looked to convert vacant office buildings into residential accommodation, with the potential to unlock new supply in the lower to middle income segment.[11] In Chicago, previous and present mayors have shepherded several immense conversion projects within the Chicago business district, with a plan to convert vacant office buildings into mixed use developments. The residential components target at least 30% of units to be designated for affordable housing.[12] Overall, the projects represent a $528mn investment, and have the potential to offer $150mn in tax incentives to developers.[13] It should be noted the success of adaptive reuse developments are likely to vary project to project, and from sub-market to sub-market. The floor plans of many NYC skyscrapers, for example, can often render conversion to residential units nearly impossible, and such caveats need to be taken into account, as the conversion story is often touted as a panacea to address demand problems with commercial real estate and the office segment.

Global solutions: Vive la France

Looking around the world, which countries or cities get housing policies right? Accordingly, what solutions have been piloted in other markets and might be applicable to alleviating the crisis of affordability in the US? France actually presents a standout example of a country where changing regulations—and nimble private capital—have aligned to create sustainable, long-term solutions for low to middle income housing. In fact, between 2001 and 2019, approximately 1.8 million social housing units were developed in France (roughly 100,000 per year).[14] This stands in contrast to the supply of affordable housing in other European markets, such as the UK, which has markedly declined since the 1970s.[15]

Crucially, in a country in which micro, small, and medium enterprises constitute 99.9% of all businesses, policymakers in France connect the provision of housing in high cost jurisdictions such as Paris with economic policy to support growth and entrepreneurship. Essential workers—including firefighters, teachers, and bakers—are among those receiving an allocation of affordable housing to be near their place of work in the City of Light.[16] The provision of housing is just one aspect of <<la mixité sociale>>, a policy of urban renovation designed to reshuffle stubborn class rigidities in France (which also includes a rejigging of lycées, or secondary education schools)[17].

In the real estate landscape in Paris, this is evidenced in the increase of mixed use developments and the provision of affordable housing in the heart of the city (in contrast with policies of old and past segregation instilled in les banlieues). Indeed, in one much vaunted recent project, la Samaritaine, the redevelopment of an iconic department store also incorporates 96 social housing dwellings.[18] The development—and the bolstering of mixed use and mixed income housing projects overall—illustrate the extent to which changing regulations have actually culminated in a progressive alignment between local policymakers and private capital on housing,[19] resulting in a sustainable increase in low to middle income housing stock, the support of micro and small businesses, and hence of entrepreneurship and employment in France.

Applying these solutions to the US

Some of these solutions—including the ability to roll out more mixed income housing as well as mixed use developments—are directly applicable to US gateway cities with an elevated cost of living (on par with Paris). As one industry body lucidly points out, the ability to provide market rate rents within the same development as affordable units enables developers to cover costs of affordable units with proceeds accrued from market rate units.[20] Additionally, the ability for local communities to work collaboratively with developers on mixed income housing also has the potential to provide a supply of affordable housing amidst shortfalls in federal funding.[21]

Moreover, the inclusion of mixed use developments alongside mixed income housing offers an enhanced quality of life with amenities—much in the way the Samaritaine project has evolved in Paris. Recent projects in New York and New Rochelle can serve as strong examples for other gateway cities and suburbs in the US beset with high shelter costs.[22] Indeed, the very prospect of community leaders working together with private developers in order to address shortfalls in housing represents an important stride forward in removing some of the stigmatization around the role of private capital in real estate development. If such a change in mindset can happen in Paris, it can indeed unfold in the US!

Conclusion: The power of private capital, ESG, and the new 2030 goals

In considering the provision of affordable housing within the wider sustainability matrix, we might even ponder the ways in which investors and developers can look beyond the ‘E’ in ESG, and make additional 2030 goals within the ‘S’—or social issues—related to ESG.

Given the close interrelationship between housing and innovation, entrepreneurship, and sustainable economic growth, the ability to address critical shortfalls in the supply of affordable housing offers investors and executives a new guidepost for their 2030 commitments. In fact, this prospect is aligned with certain metropolitan agendas: greater Paris has actually put forward a goal to make 30% of its shelter affordable by 2030. And, even looking to 2030, the UN estimates that the demand for affordable (and accessible) housing units equates to a need for 96,000 new units every day.[23]

With this in mind, several of the world’s most prominent pension funds have taken action to deploy capital to affordable housing projects. From the Netherlands to Australia,[24] and from the UK[25] to Ireland, pension funds are stepping up allocations to affordable housing, in part, via innovative fund structures; by responding to an increase in government incentives, generating efficient P3 structures[26]; and also by joining up with European investors on a pan-European portfolio[27]. Certainly, there are ways in which the regulatory landscape in the US can also shift in order to spur more US institutional investors to allocate toward the development of new supply of affordable housing, commensurate with growing demand.[28] The ability for state and local governments to share effective practices on zoning reforms is one such measure.[29] A rich collaboration on innovation in construction techniques might also incentivize more strategic capital to enter into affordable housing development.[30] Moreover, for institutional investors with a FinTech or PropTech arrow in their quivers, the ability to deploy Fintech to an affordable housing part of their portfolios has the potential to create a win-win scenario: such as the use of FinTech to provide access to credit for first-time homebuyers, which can then boost diversity in home ownership.[31]

In sum, as institutional investors increasingly respond to both a fiduciary duty as well as a growing responsibility toward evolving ESG mandates and the stakeholder agreement, the ability to combine a bond-like return (or an ‘acceptable level’) with providing solutions to one of the most pressing social issues of our time presents an opportunity for truly sustainable investing. As this author and others have highlighted, stepping up allocation to affordable housing can also provide a ballast for a steady return amidst an economic downturn or a recession: for demand for affordable housing remains ever strong, in spite of fluctuations in the business cycle.[32]

Finally, such investments have clear potential to play a positive feedback loop into generating economic growth: in the short term, by stemming the cost of living crisis within the US and stemming the persistence of multiple inflation shocks within many jurisdictions; and also, over the longer horizon, by bolstering the productivity of workforces, and amplifying the quality of life across social divides within urban communities.

REFERENCES

[1] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-03-11/us-financial-insecurity-at-a-record-as-higher-cost-of-living-makes-saving-hard

[2] See discussion with Austen Goolsbee: https://www.cfr.org/event/c-peter-mccolough-series-international-economics-austan-goolsbee

[3] https://www.nar.realtor/blogs/economists-outlook/housing-affordability-hits-historical-low-in-august-2023

[4] https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/reports/files/Harvard_JCHS_Americas_Rental_Housing_2024.pdf ; see also:

[5] https://www.bls.gov/cpi/factsheets/owners-equivalent-rent-and-rent.htm

[6] See, for example, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/se-asia/residents-spruce-up-effort-a-bright-spot-amid-malaysia-s-affordable-housing-woes ; https://www.habitatforhumanity.org.uk/country/philippines/

[7] https://www.perenews.com/affordable-housing-a-global-problem-demanding-local-solutions/

[8] See, for example, work on agglomeration effects by Ed Glaser.

[9] See, for example, https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/professionals/housing-markets-data-and-research/housing-research/consultations/prohibition-purchase-residential-property-non-canadians-act

[10] See: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-07-24/cerberus-highgate-miss-payments-on-415-million-hotel-mortgage ; https://www.wsj.com/real-estate/commercial/commercial-real-estates-next-big-headache-spiraling-insurance-costs-604efe4d ; https://www.novoco.com/notes-from-novogradac/lihtc-property-insurance-increased-2022-jump-differed-area

[11] This spike in property insurance is – of course – not unique to the US. One observer shrewdly noted the rise in the climate-related aspects of insurance has effectively rendered a carbon tax on property investors.

[12] https://www.ctvnews.ca/business/solving-shortage-of-construction-workers-key-to-housing-growth-experts-1.6852062#:~:text=Canada%20could%20need%20more%20than,assistant%20chief%20economist%20Robert%20Hogue.

[13] See, for example, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/a-snapshot-of-housing-supply-and-affordability-challenges-in-atlanta/

[14] https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/a-snapshot-of-housing-supply-and-affordability-challenges-in-atlanta/

[15] See, for example, https://cre.org/real-estate-issues/build-this-house-real-estate-opportunities-in-the-u-s-under-biden/ ; https://www.housingfinance.com/finance/industry-adapts-to-the-new-4-lihtc-rate_o

[16] https://www.bisnow.com/national/news/affordable-housing/low-income-housing-tax-credit-123179

[17] https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-10-08/nimby-paradox-australias-housing-crisis-higher-density-homes/102917248

[18] https://therealdeal.com/new-york/2024/04/17/state-budget-expected-to-lift-new-york-citys-far-cap/

[19] See, for example, https://www.6sqft.com/nyc-proposes-high-density-zoning-districts-if-far-cap-lifts/ ; https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/232-24/adams-administration-initiative-create-tens-thousands-affordable-homes-in

[20] For NYC provisions, see: https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/602-23/mayor-adams-dcp-director-garodnick-proposal-convert-vacant-offices-housing-through#/0

[21] https://abc7chicago.com/lasalle-street-reimagined-chicgao-mayor-brandon-johnson-loop-affordable-housing/14610938/

[22] https://abc7chicago.com/lasalle-street-reimagined-chicgao-mayor-brandon-johnson-loop-affordable-housing/14610938/

[23] https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/housing/social-contract-parisian-social-housing

[24] https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/housing/social-contract-parisian-social-housing

[25] https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/17/realestate/paris-france-housing-costs.html

[26] See, for example, https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2024/04/17/la-ville-de-paris-veut-accelerer-sur-la-mixite-sociale-en-augmentant-le-pastillage_6228258_3224.html ; See also: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/lessons-france-creating-inclusionary-housing-mandating-citywide-affordability

[27] https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/housing/social-contract-parisian-social-housing

[28] See also: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epub/10.1177/23996544221129125

[29] See, for example, https://nhc.org/policy-guide/mixed-income-housing-the-basics/common-incentives-and-offsets-in-mixed-income-housing/

[30] Some federal funding programmes have not kept up with rising construction costs and land values. See, for example, https://www.gao.gov/blog/affordable-housing-crisis-grows-while-efforts-increase-supply-fall-short

[31] See, for example, https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-completion-179-unit-mixed-use-affordable-housing-development-new ; https://nrpgroup.com/communities/renaissance-at-lincoln-park

[32] https://unhabitat.org/topic/housing

[33] https://realassets.ipe.com/news/super-funds-create-ifm-managed-vehicle-for-affordable-housing-investment/10071796.article ; https://realassets.ipe.com/special-reports/affordable-housing-abp-and-bpfbouw-team-up-for-impact/10071241.article

[34] https://www.pionline.com/alternatives/uk-plans-incentives-pension-funds-build-affordable-homes

[35] https://realassets.ipe.com/special-reports/can-institutional-investment-in-affordable-housing-keep-up-with-demand/10071231.article

[36] https://www.iberian.property/news/residential/patrizia-closes-eur500m-fund-to-invest-in-social-and-affordable-housing/

[37]On US pension fund allocation, see: https://www.newyorkfed.org/newsevents/news/regional_outreach/2024/20240229.

[38] https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-the-federal-government-can-do-to-increase-the-supply-of-affordable-housing/

[39] See, for example, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/housing-affordability-five-actions/

[40] See: https://www.richmondfed.org/-/media/RichmondFedOrg/publications/research/econ_focus/2023/q1/opinion.pdf ; Also, as several World Bank researchers highlight, the marriage of Fintech with the ‘rent to own’ phenomenon has the potential to unlock significant supply of affordable housing within emerging market / developing economies. See: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/psd/can-rent-own-20-offer-affordable-path-homeownership-emerging-economies

[41] See, for example, https://cre.org/real-estate-issues/build-this-house-real-estate-opportunities-in-the-u-s-under-biden/ ; see also: https://prea.org/publications/quarterly/affordable-housing-stable-returns-with-positive-social-impact/

@N Universe/Shutterstock.com

@N Universe/Shutterstock.com