I have been concerned with business ethics ever since I was initially entrusted with the responsibility of managing the careers of others some 20 years ago. The desire to become more aware of the ethical underpinnings of business behavior has led me on a lengthy tour of business literature and the social sciences of organizational behavior as well as moral philosophy and theology. As a result, I have found myself a teacher of ethics in graduate business schools, in churches and even in a seminary. The anecdotal behavior patterns over the past years in my chosen profession, investment banking, have added to the drama of my personal quest.

Many argue that ethics cannot be taught, especially to young adults whose values already have been formed. I shall discuss this issue in some detail below, but one might even cede this premise and still find a valuable purpose in teaching ethics. I attempt to blunt the issue by stating my purpose in an ethics class is to take a very brief tour through ethical decision making. What are the issues? Who are the stakeholders? If one can merely raise the group’s ethical awareness and imagination, a great deal has been accomplished.

When I teach a 90-minute ethics orientation class to incoming MBA candidates at a major graduate school of business, I suggest they spend an extra five minutes on each case they are assigned and jot down any ethical issues they can see. After two years and hundreds of cases, their ethical imagination can be sharpened immeasurably by this process.

I caution the students not to raise all these issues in the classroom. No one wishes to be thought of as an obstructionist, always wearing one’s heart on one’s sleeve. As we shall discuss in this article, the truly great ethical clashes in our lives, where we must make a stand or lose our sense of humanity, are quite rare. We often magnify into great ethical issues, those issues where we lose out to others, where we are right and everyone else is wrong. If we can allow ourselves to broaden the list of potential stakeholders from a small party of one, we may come to see the issue in a new light. Warren Buffet has stated that a full business career involves possibly as few as 20 truly career-making decisions.

I urge students to develop their own awareness of ethics and to begin feeling more comfortable with the paradox and ambiguity of professional life. I urge them to develop a community in which they can comfortably discuss and share ethical concerns which trouble them without having to “go public” every time they are uncomfortable. Above ail, I urge them to begin to know what are their real limits, where they will take their stand. The worst thing that can happen is to walk through a major ethical dilemma unconsciously carried along by the crowd, only to become blind sided into doing something that would be inconceivable to you in the full light of day.

When I talk about professional ethics, I speak in the context of one who has spent 30 years as an investment banker, where the rewards and recognition are meted out primarily on the basis of one’s prowess in doing deals. Accordingly, t became an expert in serving client needs, thwarting competition, dealing, negotiating, compromising, prevailing, pushing the limits, living on the edge, and living with ambiguity and paradox. Later, as a manager, I became adept at influencing others to do the same.

At the same time, a core of us built the business in our firm from an employee base of 120 thirty years ago to 7,500 today. Such dramatic growth required focus and prioritization, coherence and clarity of purpose, rewards and punishments, trading off empowerment and control. We could not be so rigid that we could not push ourselves to the edge of the envelope in creating new businesses and markets. Nor could we be so devious and amoral that we could not command the respect of our colleagues and clients. Above all, we had to build systems and procedures that supported om risk takers.

We learned that the seemingly small, informal actions of the senior managers could have far greater impact than the formal management systems. Donald Siebert, former CEO of JC Penney, liked to tell little vignettes of improper senior management behavior.

“Keep it out of the Board Report!”

“Get my niece a job!”

“I don’t care what you call it-call it corporate expense!”

Thus, over time, is the culture established.

Bad practices grow incrementally. Each small twist of the wheel goes unnoticed. People are rewarded for behavior which reinforces bad practices instead of good practices. We are told from natural science that a frog will sit in a pan of tepid water as the heat is slowly turned up until it dies. While, if the frog is thrown into over-heated water, it will jump out. Entitlement replaces responsibility. We each have our own vision of organizations gone awry; and as we wonder how senior management could have condoned such bad practices, perhaps the only answer is the incremental gradualism of evil where there is a lack of moral awareness or imagination.

Organizations where bad practices are condoned and even rewarded develop a pluralistic ignorance. Individual ethics and good practices are drowned out by the cultural norm of the group in ignoring them. We have s en examples of this in the 39 New Yorkers refusing to hear the screams of Kitty Genovese; in the Jim Jones mass suicides; in the reformed church in Nazi Germany; and in many of our large organizations.

Sometimes a single individual can change the course of an organization, though he takes great risk in so doing. Václav Havel terms politics, “the art of the impossible.” I am reminded of Hannah Arendt’s amazing tribute to William Shawn, the great editor of The New Yorker: “He had perfect moral pitch.” It is too bad we cannot all work for such a master.

We are each individual moral agents with great potential to do good as well as evil. The problem is that we rarely live up to our potential and that we too readily give up our moral authority to others, including the organizations where we make our living. Let me give you a couple of simple illustrations.

There was a sociological experiment where a so-called teacher and a so-called pupil were in cahoots. The unsuspecting target was told that the student was a poor learner and required motivation. The teacher had invented an electric shock device to motivate the student. The target was told to shock the student each time she gave a wrong answer, in order to test the new device. This test was administered on a college campus under the rubric of research.

Of course, the putative student always gave the wrong answer, and by and large the target kept turning up the juice, even into a danger zone marked on the device. The student appeared to be in pain. Afterwards, when the target was debriefed, he claimed he was only following instructions.

Likewise, many years ago, at the Union Theological Seminary, Columbia University, an authority figure ordered a series of seminarians to drop everything and fetch a paper off his desk, located in another office, and return it to him immediately. In order to fetch the paper, the seminarians had to step twice, going and coming, over the body of a prostrate student lying on a rug in the outer office. In most cases they performed the mission without providing assistance to their prostrate peer. Once again, afterwards, they said they were just obeying orders.

Sound familiar? This is what Hannah Arendt described as, “the banality of evil.”

Types Of Ethics

A problem in discussing ethics is deciding which language to use. Few of us are accustomed to expose our individual ethics before a group. We tend to become defensive. In today’s norm of cultural relativism-“I’m OK, You’re OK” -we are reluctant to publicly criticize the value systems of others. In a graduate business school, learning is compartmentalized into marketing, production, control, finance, human behavior and the like. Ethics intrudes into all those areas but without a common language. I have found it useful in discussing ethics to attempt to frame a definitional language by discussing types of ethics. The following list is by no means inclusive. It is meant only to gain a primitive hold on a possible common language.

Normative ethics

In simple terms, normative ethics is that behavior which society at large condones as proper over time. Normative ethics may be codified as the law, but it embraces large areas of behavior not codified by the law. It encompasses our behavior in groups (Do not yell “Fire!” in a crowded theater.); expressions of our sexuality; our dress; and the like. Cultural relativism is a current norm, as is situational ethics. There are those who would say that today’s norm is that there are no rules, no easily identifiable broad set of values in which we can all agree. It is easy to go along with the norm; but the norm can easily lead to the incremental gradualism of bad practice as well as pluralistic ignorance.

A very important aspect of normative ethics is that it changes over time as people’s attitudes change. Sociologists have even described long wave rhythms of societal norms swinging back and forth between conservatism and liberality. Thus, if we base our behavior purely on societal norms, we must be prepared to have the rug pulled out from beneath us. Somewhat arcane but valid illustrations would include price fixing, anti-trust, insider trading, or the non-payment of social security taxes for part-time domestic employees. If we base our behavior on current norms, we might find ourselves a criminal 20 years in the future.

Kantian ethics

Named after the famous 19th century moral philosopher, Kantian ethics has come to mean rigid ethical rules or duties. Attributed to Kant is the categorical imperative; which is to say, there are certain things we simply must do in order to maintain our basic humanity. As much as certain elements of our normative society are crying out for at least some rules to live by, others would say that Kant’s approach is too rigid for contemporary society.

An apocryphal extension of Kantian ethics would be to recount a story of World War II Amsterdam when Anne Frank knocks on your door and you hide her in your attic to save her from the Gestapo. When the Gestapo knocks on your door and inquires as to Anne’s whereabouts, you tell them she is hiding in your attic. According to Kant, there is never a good excuse for a lie.

I tell this story to my students; then I tell them they are each Kantians. They object to this. As living practitioners of normative ethics, they could never be so rigid. Yet, I repeat my charge. We are all Kantians. The trouble is, we are each Kantian about different things. For each of us there are certain things we could never cause ourselves to do. In doing them we would lose our humanity. Yet for each of us the limits are somewhat different. This is what makes governance so difficult for any type of social structure; and this is why, in an age of cultural relativism, we often come together at the lowest common denominator or at the worst bad practice.

Utilitarian ethics

Stemming from Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, utilitarianism (the greatest good for the greatest number) is a powerful shaper of our normative ethic. Utilitarian ethics drives government policy-making, economic input/ output modelling, cost-benefit analysis and basically determines how our world works. Health care reform is based on utilitarian ethics. As a society we will not condone paying $500 for a pint of blood when it is commonly available at $100 a pint. The odds of contaminated blood may be 1:100,000 at $100 a unit, and 1:1,000,000 at $500 a unit. We as a society do not think that is a good trade. But if our loved one is infected through contaminated blood, we will sue the hospital for millions of dollars for not using the more expensive blood.

We can calculate the value of a human life and enter the sum into our input/output models to determine how many kidney dialysis machines we can afford economically. We can calculate your future earning power. We can also calculate how much you would be willing to pay to save your own life. A result is that people’s lives are worth more in wealthy countries than in poorer countries. The Economist, for example, reports that a human life is calculated to be worth $2.6 million in America and $20,000 in Portugal. McNamara ran the Vietnam War on an acceptable kill ratio of 20:1. They killed 56,000 of ours, and we killed over a million of them. The Gulf War will be a prized case of a successful kill ratio (unless, of course, someone you loved was killed).

Utilitarian ethics are pervasive in our society. The majority vote wins. The only real losers are the minority.

Social justice ethics

Social justice ethics is an antidote to the excesses of majority ruled utilitarianism. It takes care of those who lose out to the mainstream of society. The social safety net is a good example of social justice. Critics of social justice politics brand it as single issue politics, or the tyranny of the minority.

Religious ethics

As we shall discuss in this article, moral philosophy and theology play a major role even in normative ethics. Will Durant writes in “The Story of Civilization:” “Conduct deprived of its religious supports deteriorates into epicurean chaos; and life itself, shorn of consoling faith, becomes a burden alike to conscious poverty and to weary wealth.” The issue for society of course is which religion do we choose? Even in a country like Nepal, with an announced state religion, religious diversity is present. The problem, of course, is that nothing has divided mankind more throughout history than religious differences. In the United States, where religion is pervasive in our normative culture, we continue to attempt to preserve the notion of the secular state. In his recent book The Culture of Disbelief, Stephen L. Carter writes of the ubiquity of religious language in our public debates as a form of trivialization of religion, as our politicians repeat largely meaningless religious incantations.

Communitarian ethics

A more secular and perhaps less controversial approach to moral theology, but based purely on the social sciences, is communitarianism. Most recently espoused by Amitai Etzioni in his book The Moral Dimension and reported by Time magazine, communitarianism relies on: (1) the individual, (2) society, and (3) transcendent values. Transcendent values can be any of the world’s religions, or even a deeply rooted humanism.

The great Protestant theologian, Paul Tillich, discussed evil in terms of isolation, loneliness and alienation. We must be in community with ourselves, our community and our God. Such a theology is validated by the great depth psychologists.

To many of us, communitarianism resonates from the one great commandment of the New Testament: we must love ou neighbors as we love ourselves (which means implicitly, by the way, that we must first love ourselves), and we must love the Lord our God with all our heart and all our mind and all our strength. This commandment may be found in the Jewish and Islamic religions as well. The universality of the e ideas may not be completely accidental.

This brief review of a few ethical systems is meant only to begin bringing clarity to our thinking. So often we bring all these systems to bear in a single conversation, confusing the listener as well as ourselves. I enjoy listening to a presidential debate and saying to myself, ”Aha, that’s utilitarian. Now he’s a Kantian. No, that’s normative.” It is helpful to begin developing a language of ethics if we are ever to reason together.

One Ethics Model

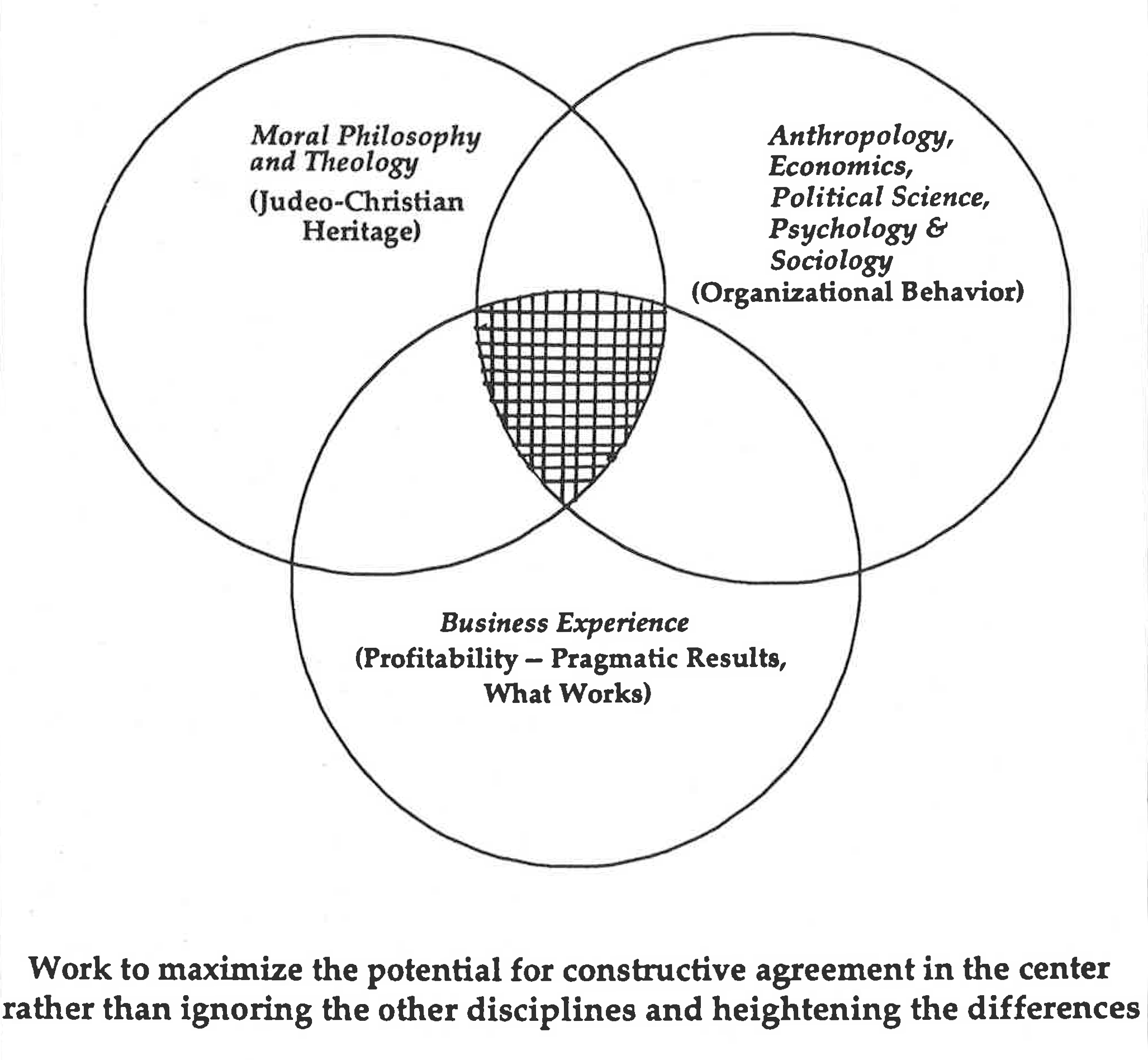

Ethics babble persists because ethics crosses so many lines. The following illustration makes the point. Moral philosophy and theology provide the ethics underpinnings. The social scientists, including also economists and political scientists, intellectualize about how ethics actually works. Practitioners, managers and leaders have pragmatic experience which is invaluable in determining how to foster and stimulate an ethical corporate culture.

The schematic diagram indicates that all inputs are essential and that the area of overlap is small. Very few academics or practitioners are confident when expressing themselves in all three areas. Universities are not organized to foster such cross-discipline specialties. Too often we are left with business people knocking the doors down in a church, church people knocking down the doors in a business and academics lecturing to a non-audience.

Business schools and universities do not deem it appropriate to teach theology, moral philosophy or values. These must be taught at home. Such edicts ignore the fact that the majority of students were not reared in a nuclear family and that according to the findings of social scientists, in the aging of mankind the search for meaning and values becomes even more pronounced in late middle age. The younger upwardly mobile are not too old to learn values; they are too young and overwhelmed by career and family chokes. I differ from the majority view in my feeling that moral philosophy is entirely appropriate to include in a business school ethics class. Students are hungering for values and for ideas upon which they can build in later stages of their continuing growth.

The other two circles—social sciences, including organizational behavior, and pragmatic business experience—are entirely appropriate curricula for a business school. A solid case can be made for a course in ethical awareness, imagination and decision-making utilizing just two of these spheres of knowledge; but, in my experience, students need and appreciate the third as well.

Finally, business school administrators assert that values certainly cannot be taught or graded. How, in an age of cultural relativism, can we grade someone’s values? My own experience indicates that almost any case study has more than a single answer. We are not grading answers, we are grading the ability to ingest large amounts of data offered in a jumbled state; to provide clarity, prioritization, and focus; and by way of an intelligent and ordered reasoning process, to discern a viable plan of action. At least that’s what I thought the top business schools did.

One Way of Thinking About a Viable Approach to Business Ethics

Ethical Decision Making

I am indebted to my friend, Michael Josephson of the Josephson Institute of Ethics, for much of the structure which follows. Michael proposes a five step ethical decision making process which I shall discuss in some detail.

Identify the stakeholders.

Paul Tillich writes that if we become insolated moral agents we are almost certain to commit immoral acts. We find our morality in community, removing our ego and letting in the world. Many social scientists echo Tillich’s theology. Teachers of ethical reasoning urge us to include as many stakeholders as imaginable in our decision making process. The more creatively and imaginatively one begins to think about broadening the list of stakeholders, the more ethically aware one becomes. What about Michael Millken’s children? What about the children of laid-off workers in a takeover? Moreover, the broader the community of decision makers, the broader the list of stakeholders. I urge my students to avoid isolation. A peer group on the job to discuss issues is always best. Since we do not always work in an open environment, a professional peer group of ex-classmates, a church professional group or trusted close friends becomes essential.

Identify the ethical principle.

We often confuse our hurt feelings or disappointments for ethical issues. Through discussion, be certain a real ethical issue exists. My father always told me: “You get your loving at home!” If there are only 20 or so key issues in a career, be certain you are not using yours up too rapidly. Ethics is tough-minded business. If utilitarianism is the norm, begin to discern the difference between the issues of being in the minority and basic unfairness or lack of integrity. Strip out the emotion. Ethics trumps expediency.

Choose one ethical principle.

The true spirit crushing ethical dilemmas are when one is caught between two opposing powerful ethical issues. These are among the 20 big time file decisions. If you are to be human and act out your own life, you must make a choice. To refuse to choose is to lack integrity. This is the stuff of great drama and great literature.

Paul Tillich in his “My Search For Absolutes” wrote: “… no moral code can spare us from a decision and thus save us from moral risk …. Moral commandments are the wisdom of the past as it has been embodied in laws and traditions, and anyone who does not follow them risks tragedy …. Moral decisions involve moral risk. Even though a decision may be wrong and bring suffering, the creative element in every serious choice can give the courage to decide …. The mixture of the absolute and the relative in moral decisions is what constitutes their danger and their greatness. It gives dignity and tragedy to man, creative joy and pain of failure. Therefore he should not try to escape into a willfulness without norms or into a security without freedom.”

Likewise in his autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Carl Jung writes of the existential anxiety of moral decision making: “We must have the freedom in some circumstances to avoid the known moral good and do what is considered (e.g. normative) to be evil, if an ethical decision so requires. As a rule, however, the individual is so unconscious that he altogether fails to see his own potential for decision. Instead he is consistently looking around for external rules and regulation which can guide him in his perplexity.”

In resolving true ethical choices, be certain to understand why you chose the path you chose and why you rejected the path you rejected. Loyalty is perhaps the weakest ethical _standard, and the preservation of human life may be the strongest. You must be tough enough to make a decision when you have sought out divergent points of view and all that needs to be known cannot be known. You must at times answer questions which have no established solutions.

Creatively examine options.

We so often lock ourselves into a binary decision path. The answer must be either/or. Yet so many issues come at us all jumbled amidst ambiguity and paradox. We often sail right through without even discerning the ethical issues, or else we make a snap either/or judgment. The ambiguity of many dilemmas cries out for a polyphonous response. Stop, gather your community of peers and come up with as many options as possible for consideration. Perhaps, for example, in a downsizing strategy, instead of firing everybody, you can afford to keep their health benefits going for an additional six or twelve months.

Maximize long term benefits.

We are back to the utilitarian model once again. Note the key words “long term.” A broad list of stakeholders Will help move from my short term needs to the long term needs of others. At an earlier step, we suggested stripping out emotion. Perhaps at this final step we may re-integrate emotion and compassion. The utilitarian greater good must be balanced with the need of the minority. Solutions may appear ambiguous. We may both rely on virtue and impose sanctions. We may empower others with our solutions, but we will also insist on accountability. The best solutions may follow the tight-loose Peters and Waterman model described in In Search of Excellence—a model of freedom with control.

Ethics Of Organizations

We have been speaking, thus far, of individual ethics; but what of institutional ethics? How do we inculcate an ethic within an organization or an institution or a society? There are those who say that in an age of normative ethics and utilitarian ethics, our institutions no longer work for us.

In his recent book on professional compensation, Derek Bok quotes T. S. Eliot: “As a society we much prefer to leave our values undisturbed while going to great lengths to create in T.S. Eliot’s words, ‘a system that is so perfect that no one needs to be good.'”

In many ways each of us is as much a social justice or single issue politician as we are a Kantian. We take umbrage when we find ourselves in the minority within the context of an organization, institution or society at large; and we wrap ourselves in the cloak of moral self-righteousness and attack the “evil” organization that has done us in. Yet we know in our hearts that good leaders require good servants. In fact, as the late Robert Greenleaf noted, good leaders need to be good servants. We must each learn to be loyal members of institutions while retaining our individual ethical vigilance.

Perhaps John Gardner came closest to describing the covenantal relationship required between individuals and organizations in his fairly recent Stanford commencement address. Gardner stated that we must find a wholeness incorporating diversity. We must neither suppress it nor make it a tyrant. We must respect diversity. Each of us must ask what we can contribute to the whole. Gardner concludes that wholeness incorporating diversity defines the transcendent task of our generation.

Conclusion

Ethics is not easy or loose. Ethics is tough and hard. We must learn and decide who we are. Where do we draw the line? What are we willing to lose for? Ethics isn’t always winning. Cheaters do prosper. Ethics is losing in the short term for a longer term sense of self-worth and transcendent values. Learning to live ethically is learning to live with oneself, learning to live in community and learning to live in that great stream of humanism, including theology and religion, that forms our Western culture. It is not a process that is completed at our mother’s knee or in graduate school. For the truly conscious person, it is a lifelong process of growth and maturation which, by its very nature, can never be perfect or complete.

Photo: Olivier Le Moal/Shutterstock.com

Photo: Olivier Le Moal/Shutterstock.com