Housing shortages once mainly confined to the coasts have made landfall in places like Boise, Idaho, and Bozeman, Montana. According to Freddie Mac, the United States “is short 3.8 million housing units to keep up with household formation.”

While other factors—including land costs, lack of available land, and high labor costs—contribute to the housing shortage, experts agree that overly restrictive zoning policies are a major part of the problem.

State legislation designed to preempt or circumvent local exclusionary zoning rules and burdensome and costly permitting and variance processes is a promising, yet often improperly and underutilized, tool to expand the affordable housing supply. Zoning preemption is attractive because it comes at a lower cost to the taxpayer than solutions like government tax credits or housing vouchers, and it empowers private developers—in other words, folks in the business of actually building housing—to build. Done correctly, state preemption can marry democratic values with free-market capitalism to address a major societal need.

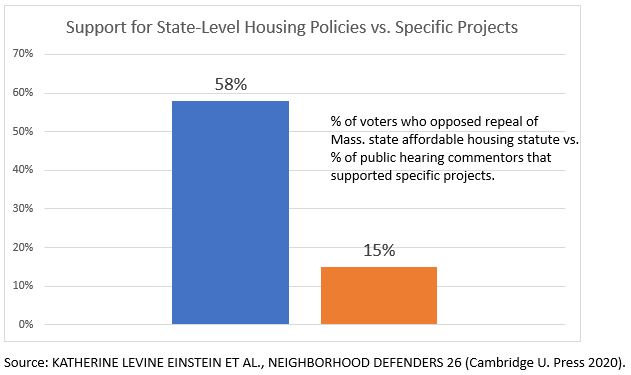

States are better positioned to address restrictive land use policies than municipalities (or the federal government) for many reasons. First, local governments, which rely on property taxes to provide services, fear that an apartment development, which typically generates less property tax revenue per capita than single-family housing, will be too costly to the government in terms of the services-to-tax-revenue ratio, although this fear is often unfounded. Additionally, multifamily development is often unpopular among homeowners in the neighborhood of the proposed development, so local politicians have an additional incentive to oppose it. Residents who oppose the development can mobilize to block it (or vote against politicians who support it), but those in favor of the development are less likely to mobilize to support it. But state-level debates center on affordable housing generally, not on specific projects. “[W]hen land use decisions are made at the state level, people can vote their values, not their most parochial fears.”

Assuming that state politicians want their states to continue to be (or become) viable places for their populaces to live, they have a duty to act.

Affordable housing is such a broad challenge that it is unlikely that any single solution could address it, but a range of policy options could help state governments motivate private sector action. A multifaced state-level strategy could include (1) allowing accessory dwelling units in single-family neighborhoods, with permitting processes no more strenuous or costly than those for single-family homes; (2) banning single-family zoning entirely; (3) allowing residential construction in commercial zones without cumbersome and often arbitrary barriers; (4) creating state-level housing appeals boards and subjecting all municipalities to them; and (5) banning minimum parking requirements.

I wrote a paper exploring these strategies in the fall of 2022, which was published by The Denny Center for Democratic Capitalism at Georgetown Law in the summer of 2023. Below, I explore what has happened since I wrote the original article.

Accessory Dwelling Units

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) remain one of the easier state-level zoning preemption programs to implement and would have the effect of banning single-family zoning. ADUs are less controversial than apartment buildings because they introduce fewer new neighbors (i.e., don’t alter the neighborhood’s “character”) and have less impact on street, water, and utility use.

Since I wrote my initial paper, Montana and Washington have joined California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont as states that have preempted municipal zoning laws around ADUs to at least some degree. Encouragingly, both states passed bills that require cities to allow ADUs by right, with owner-occupancy requirements and most parking requirements prohibited. The Montana bill was sponsored by Republican state legislators, and the Washington bill was sponsored by Democratic state legislators, and both passed with bipartisan support. Unfortunately, a judge recently issued a temporary injunction blocking the Montana law in response to a lawsuit from a NIMBY group in state court. The ruling will almost certainly be appealed, so it will likely be years before, at best, the law is reinstated.

Washington’s ADU law legalizes two ADUs on any lot legally large enough for a single detached house. Unfortunately, most cities won’t be required to bring their local zoning laws into compliance with the state law until mid-2025, at the earliest.

Still, the fact that these states were able to pass these laws with bipartisan support demonstrates that state preemption can work. And while ADUs cannot solve the housing crisis on their own, they can chip away at the housing deficit. Seattle has already seen a more than 250 percent increase in ADU permits since it changed its local zoning regulations to encourage ADU developments in 2019. California issued more than 22,000 permits for ADUs in 2022, up from 1,300 in 2017, and Los Angeles issued more than five times as many ADU permits in 2022 as it did single-family permits.

Connecticut’s 2021 ADU law allowed towns to opt out of permitting ADUs by right—and many did—but two-thirds of towns allow accessory dwelling units that at least partially satisfy the state law’s requirements. The Montana and Washington laws, which don’t allow towns to opt out, are better models for states looking to implement their own ADU laws.

Banning Single-Family Zoning

As of 2019, 75 percent of the residential land in the U.S. was zoned exclusively for single-family use. Zoning that does not allow for any multifamily development is arguably as “exclusionary” as zoning gets without violating the equal protection or due process clauses of the U.S. Constitution.

In 2019, Oregon essentially banned single-family zoning statewide. It was able to do this through a coalition of supporters that “included urban Democrats, members from both parties in the tourist areas of the state (the coast and the high desert), as well as some property rights supporters from rural areas” and by using terms like “missing middle” and “middle housing” instead of “zoning” and “duplexes” and “triplexes” instead of “apartment buildings.” Unlike Connecticut towns opting out of the ADU law, by the end of 2022 all municipalities covered under Oregon’s law had complied, and almost all of them even surpassed the minimum requirements. It is still too early to truly assess the impact of banning single-family zoning, but Oregon’s average monthly housing permits for two-to-four-unit buildings have risen from 45.5 in 2018 to 67.8 through the first five months of 2023, an early indicator of success.

California passed a law ending single-family zoning in 2021, but the law left too much room for municipalities to continue to enforce maximum unit sizes, height limitations, and other regulations, which have curbed the law’s success. California would be well served to strengthen the law to limit these local regulations like it did over time with its ADU laws, which resulted in a significant uptick in ADU permitting.

Washington enacted a law to Oregon’s, which took effect in July 2023, and the state house passed a bill requiring cities to allow “residential property owners to split their lots into smaller parcels” in January 2024.

Vermont passed a law in June 2023 that “allows duplexes everywhere single-family homes are allowed and multiunit dwelling up to 4 units in areas served by sewer and water.”

Montana passed a law requiring municipalities to allow duplexes in single-family areas alongside its ADU reform law, but that law too has been temporarily enjoined by the court system. Still, the fact that Montana was able to pass these laws is progress, and even if they are ultimately struck down in court, the legislature could try again in a way that is more likely to pass muster in the courts.

It is still too early to assess the impact of these laws, and progress will be slow, but they are a step in the right direction.

Housing Appeals Statutes

A housing appeals statute is a state statutory mechanism that creates an appeals system, often in conjunction with a municipal permitting process, to ensure local governments or neighborhood defenders do not unfairly reject or drag out affordable housing development to the point where it is no longer viable.

These statutes remain under implemented and underused, but there were some notable success stories pertaining to them in 2023. Rhode Island dissolved its Housing Appeals Board and replaced it with a dedicated land use program in its regular court system, which should streamline the appeals process. As part of its housing reform law, Rhode Island passed a sort of reverse housing appeal statute, which banned “character of the area” appeals—a common NIMBY tactic—in all residential areas.

California, which has a longstanding but rarely used builder’s remedy that applies to cities that are not in line with state-mandated housing development plans, had a victory in federal district court when a judge ruled that Huntington Beach did not have standing to challenge the state development plan. While Huntington Beach has appealed the ruling to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, the ruling could open the city up to builder’s remedy-infused development. Two developers have proposed using the builder’s remedy to create two separate high-rise housing developments in Beverly Hills, one in a commercially zoned area and one that is taller than the residential area currently allows for. It remains to be seen how these developments will play out, but they indicate that use of the builder’s remedy is gaining steam.

Commercial to Multifamily Conversions & Commercial Zones

The rise of remote work, spurred in part by the COVID-19 pandemic, has lowered office-building usage and demand, leaving many buildings vacant or underutilized. Given the housing crisis, converting many of these office buildings into multifamily housing units is a logical solution. And while many office buildings are unsuitable for conversion to multifamily, local zoning and permitting regulations create unnecessary (and often arbitrary) barriers.

However, this is an area where cities have taken the lead in terms of removing arbitrary zoning restrictions, and the number of apartments scheduled to be created from office buildings increased fourfold from 2021 (12,100 apartment units) to 2024 (55,300 apartment units), according to a recent report from RentCafe. Washington, DC, where office to residential conversions are a key component of the mayor’s effort to reinvigorate the city’s central business district, has the most conversions planned, followed by New York, Dallas, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

States are also beginning to incentivize commercial to residential conversions. Notably, Rhode Island passed legislation allowing conversions as a permitted use in most circumstances as long as the developer converts at least 50 percent of the commercial building into residential units. Arizona also passed bipartisan legislation “which will allow cities with populations of more than 100,000 to reuse up to 10% of commercial buildings without requiring discretionary municipal review, bypassing the need for conditional use permits or rezoning applications.”

The Biden Administration is also encouraging commercial-to-residential conversions, releasing a guidebook in October 2023 that highlights “federal loan, grant, tax credit and technical assistance programs across seven agencies that can be used to convert commercial properties to residential use.”

Ending Parking Minimums

Municipal regulations that require housing developments to include a certain number of parking spaces add installation costs, raising rental costs, and, in many cases, limit development. Ending parking minimums would also free up land that could be used to develop housing. Parking concerns are also frequently raised at community meetings about proposed housing developments.

Cities have been driving these reforms, with more than 50 cities and towns getting rid of parking minimums in recent years. But because suburban areas need housing too, and parking requirements inhibit development, broader state preemption efforts are needed as well. Vermont’s 2023 housing reform legislation reduced parking minimums to no more than one space per unit. While this is a start, and one space per unit is likely necessary for most of Vermont, one space per unit might not be needed in states with larger urban populations.

Conclusion

While statewide zoning reforms are a start—and only a small piece of created much-needed housing—with recent successes and failures, a recent survey by Pew Charitable Trusts showed widespread, bipartisan support for many of the zoning reforms discussed in this paper. More than 80 percent of respondents were in favor of allowing transit-oriented development and commercial-to-residential conversions, more than 70 percent supported allowing apartment development in commercial zones and allowing ADUs, more than 60 percent backed allowing builders and owners to decide how much parking to create, and nearly 60 percent championed allowing town houses or small multifamily homes on any residential lot.

Clearly zoning reform has broad support, but because folks still might not want development in their back yards, states remain the appropriate parties to take action.

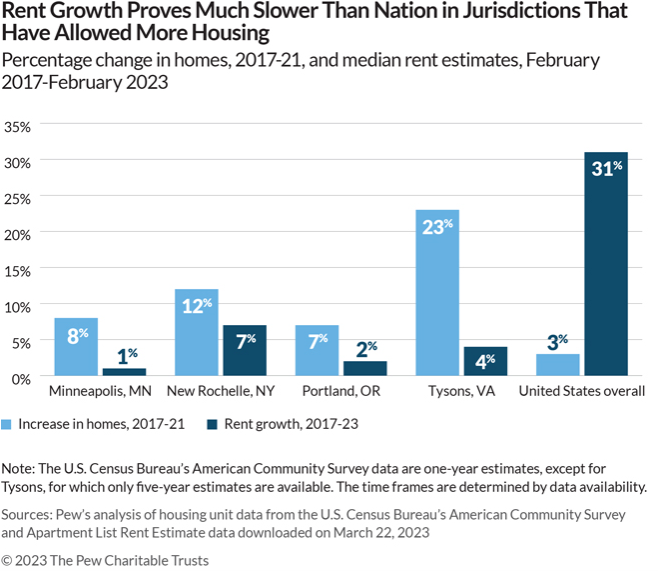

Even more encouraging, a separate Pew study examined four cities that had enacted zoning reforms, finding that these cities had more housing development and slower rent growth than the United States as a whole.

Imagine what could happen if these reforms were implemented statewide, across the country?

@Bilanol/shutterstock.com

@Bilanol/shutterstock.com