Understanding What is Happening in Nebraska

A Nebraska trial court opinion issued in February 2014 has helped to focus new attention on the process for siting major pipelines, the environment and the power of eminent domain.

In 2008 TransCanada Corporation, based in Calgary, Alberta, constructed the Keystone Pipeline through Nebraska. The Keystone project now transports crude oil from Hardisty, Alberta, to Wood River, Illinois. Additional phases of the project carry crude to the Gulf Coast near Houston, Texas. The crude oil is pumped through a 36-inch diameter pipe, utilizing 39 pumping stations along the route. The project was well known in the Great Plains, but it proceeded with little notice elsewhere. Then, the Keystone XL was announced by TransCanada. It was initially approached by TransCanada with the expectation, based on experience, that it would go as easily and smoothly as the original Keystone project. Many Americans are following the XL project on a regular basis, and as we well know, it has not been at all smooth and easy.

As a Nebraska lawyer who regularly represents property owners in condemnation, this author is naturally protective of private property rights and enjoys events that shed light on this dark corner of the law, especially when they help to shape public opinion in favor of property rights. These rights include primarily the right of a property owner to be paid just compensation when property is taken for public use, but also include issues of whether a private, profit-centered corporation should be allowed to acquire private property by eminent domain. If so, should such corporations be required to pay compensation based on a measure other than the well established standard of loss of fair market value?

These issues were raised by the initial Keystone project, along with the question of why it was so easy for TransCanada to select its preferred route through the nation’s heartland. However, the XL debate and political campaigns have grown far beyond the rights of the affected landowners.

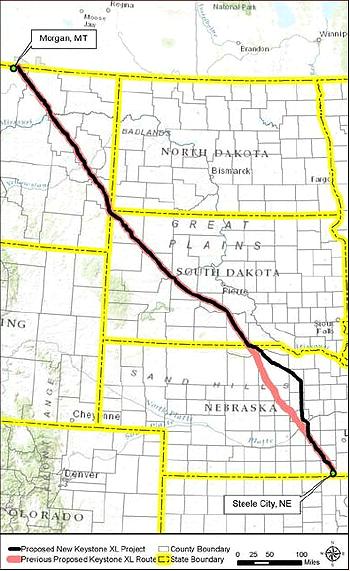

The Keystone XL is proposed to be a 36-inch diameter pipeline, 1,179 miles long from Alberta, Canada, to Steele City, Nebraska, where it will connect with the existing Keystone pipeline to move oil to refineries on the Gulf of Mexico.1 If built, it will be part of the network of more than 2.6 million miles of oil and natural gas pipelines in the United States,2 and is designed with a capacity to deliver 830,000 barrels of crude oil per day.3 Some estimates place the capacity of the Keystone system at more than a million barrels per day. The network of crude oil pipelines in the U.S. is already extensive, with approximately 55,000 miles of trunk lines, and perhaps 40,000 miles of smaller gathering lines. Several existing trunk lines in the U.S. originate in Canada.4

When TransCanada announced in 2007 that it was ready to begin acquiring pipeline corridor easements in Nebraska for the Keystone project, there was little time for opposition to organize against the project. That opposition was quickly crushed when a representative of the U.S. Department of State announced at an informational town hall meeting in Seward, Nebraska, in August 2007, that America needs Canadian oil and that the president wanted the Keystone pipeline built. Safety concerns and groundwater concerns were raised, and the science of pumping the high viscosity oil questioned, but the project was on the fast track.

The Keystone pipeline was an international project, so the permitting process ran through the president with the assistance of the Department of State.5 There was no oversight of the routing of such pipelines in Nebraska, and the Nebraska statutes at the time stated that any person or company organized for the purpose of conveying petroleum products through the state of Nebraska could acquire right-of-way for a pipeline by use of eminent domain.6 Eminent domain in Nebraska requires the agency that wishes to acquire private property to negotiate in good faith with the property owner before filing a proceeding in court to obtain the property interest.

The Keystone project resulted in very little actual use of eminent domain, but of course the threat was always present. This author is aware of only two cases filed in the state for the Keystone project. All other needed property rights were obtained through negotiations.

The photo above (Figure 1), illustrating the Keystone construction process, was taken in 2008 while the author/photographer was standing in the yard of a Nebraska farm family, approximately twenty miles west of Lincoln, and approximately 75 feet from the residence.

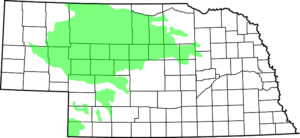

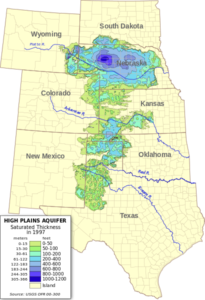

Before the Keystone pipeline was even in the ground, TransCanada announced the Keystone XL and its proposed route through the Nebraska Sandhills. The Sandhills region is a rich and beautiful grassland, perfect habitat for cattle and an abundance of wildlife. One of the most unique areas on the planet, it is the largest sand dune formation in the Western Hemisphere, with the dunes reaching up to nearly 400 feet in height. It is an almost endless sea of rolling hills covering 20-thousand square miles with few trees and enchanting river valleys. One of the area’s unique features is that the sandy hills sit on top of the heart of the vast Ogallala Aquifer, one of the largest aquifers in the world. The aquifer runs through the Great Plains from South Dakota to Texas, containing an estimated one billion-acre feet of water.

Nebraskans started asking for some oversight, some state regulation and say in the routing process. The group of opponents, though quickly quieted on the first project, had not surrendered, and they were able to regroup and gain momentum. It was apparent from the initial informational meetings that it would not be the same easy process TransCanada enjoyed before. The cry for oversight was greatly enhanced when TransCanada began issuing letters threatening property owners with condemnation if they did not sign an easement within 30 days. Of course, at the time, TransCanada did not have approval from the Department of State, and Nebraska law requires a Petition to Condemn filed in county court to state that all required approvals have been obtained.7 The condemnations were never filed, and the untimely threat only increased the resolve of the opposition. Competing advertising campaigns raged for months as both sides (perhaps it was more like six sides) fought for control of public opinion. Nebraskans would watch a television ad declaring the XL will be the safest pipeline ever built, bringing needed oil from our good friends to the north to free America from Middle-Eastern oil dependence. This would be immediately followed by a Nebraska rancher lamenting that the fragile Sandhills and aquifer would never recover from an oil spill. The economics of more jobs and an increased tax base competed with claims of legalized land seizures by a foreign corporation.

We, as well, observed competing ads on the Jumbotron during Cornhusker home football games. The Canadian oil giant apparently did not realize that Texas and Oklahoma landowners applauding the responsible and friendly manner in which TransCanada builds pipelines, in the middle of a football game in Nebraska’s Memorial Stadium, would be a less than effective way to persuade people in the Cornhusker state. By contrast, the opposition seemed to be doing everything right. In the meantime, TransCanada continued to acquire right-of-way for its planned route.

The issue of local regulation was brought before the Nebraska Legislature (the Unicameral) in 2011. The issue was whether to regulate the routing of pipelines through the state, and if so, how should it be done. There was some discussion of whether a foreign pipeline should have eminent domain authority, but that issue gained little traction with the Nebraska lawmakers. Interstate commerce and federal supremacy posed a problem for the pipeline opponents. The Nebraska Unicameral responded by passing the Major Oil Pipeline Siting Act in 2011, requiring a company proposing a major pipeline to apply to the Nebraska Public Service Commission for approval.8 The Commission is a five-member elected body with authority to regulate common carriers, authority that is granted in the Nebraska Constitution.9 Right of way could not be acquired by eminent domain unless the Commission granted approval of the pipeline. The Act specifically did not relate to safety, but only routing. The Act also did not apply to any pipeline for which an application had already been submitted to the Department of State, which meant that it did not apply to the catalyst XL pipeline.

Then, the president announced that the route through the Sandhills was rejected. Rerouting and the regulatory process immediately became the hot topic of the day. No longer was there a pending application exempting the XL from the regulatory process. The new route would be required to go through the regulatory process, and there was more time to give the matter more thought.

New regulations were added by the Unicameral in 2012, ordering major pipeline routes to be studied by the Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality, with authority given to the governor to approve or reject the route.10 If the governor rejected the proposed route, the pipeline company could then apply to the Public Service Commission. Again, eliminating eminent domain authority was briefly discussed, along with measuring just compensation based on a share of the profits, but these were never serious issues. It was not made entirely clear why primary responsibility was taken from the Public Service Commission and given to the governor.

TransCanada then announced a new route through Nebraska, intended to address the Sandhills concerns. However, the opposition was far from defeated, and pointed out that the new route would not completely miss either the Sandhills or the aquifer. Public informational meetings were held by the Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality. The proponents and opponents were always there with signs and literature, sometimes with soft drinks and pizza. The advertising campaigns geared up again.

When the reroute around the eastern edge of the Sandhills was approved by the governor, several affected landowners filed suit to have the new regulatory process declared to violate the Nebraska Constitution and to therefore be unlawful.11 The primary issue in the litigation mentioned above has been whether the XL pipeline will be a “common carrier.” The Nebraska Constitution requires that regulation of common carriers be either directly by the Unicameral or by the Public Service Commission.12 It is not certain whether a pipeline that just goes through Nebraska and does not pick up or deliver any product in Nebraska is a “common carrier,” and it was not known at the outset whether the XL would pick up any petroleum product in Nebraska. In February 2014, a state district court judge in Lincoln ruled that the XL will be a common carrier pipeline as that term is used in the Nebraska Constitution, and that review and approval of the reroute around the Sandhills was unconstitutionally delegated to the governor. The governor and other state officials were enjoined from taking action on the route that had been approved. The decision was immediately appealed to the Nebraska Court of Appeals,13 and the Nebraska Supreme Court quickly moved the case to its docket, where it is in the briefing stage on the court’s advanced docket at this writing. In the meantime, the 2011 Major Oil Pipeline Siting Act could allow the matter to go to the Public Service Commission,14 but as of the date of this writing no application has been filed with the Commission. Interestingly, TransCanada is not a party to the litigation.

The district judge’s decision was promptly hailed or booed around the nation, somewhat unusual for a state trial court opinion. It was cited as protecting private property from confiscation under the guise of eminent domain, and environmentalists cheered the victory for clean water. However, casting the litigation in either a property rights or environmental mold transforms it into something it is not. The litigation is in no way about the power to use eminent domain. The offending statutes do not give TransCanada the power to condemn, and the alternative regulatory scheme does not grant that power. It has been there all along, and even if all of the regulatory schemes offend the Constitution, that statutory power will likely remain.15 The litigation also is not about the environment, or where (or if) the pipeline should be built. It is simply about the delegation of the state’s regulatory power. Perhaps taking the ruling and making of it what we wish is to be expected when such controversial, high profile issues are involved.

The recent litigation might have some small effect on public awareness and opinion regarding the questions of who should have the power of eminent domain, and when the entity is a profit-centered corporation, should “just compensation” be measured by something other than fair market value. However, the primary legal issues will likely remain focused on the regulatory process regarding siting.

The XL is now generating a new level of frenzy almost daily. Labor unions and Native Americans are taking opposing stances. Nebraskans are traveling to Washington, D.C. to take classes on how to be arrested effectively and are camping on the National Mall with aging rock stars. On April 18, the Obama administration announced another delay in the decision on the XL to allow more time for clarity in the routing through Nebraska and to allow agencies more time to comment. U. S. senators are lining up for or against the pipeline, with a bipartisan majority of the Senate seeking a vote on legislation to override the president’s delay and to vote approval.

TransCanada’s legal problems with the XL have spread to South Dakota. The long construction delay means that the permit received from that state’s Public Utilities Commission must now be reviewed and recertified. An evidentiary hearing will take place after TransCanada applies to recertify. The opponents have made it clear that they intend to participate and vigorously challenge a recertification.16 The people of Montana have been relatively friendly toward the XL project, but the controversy has become part of the state’s 2014 election debates,17 and the Nebraska XL opponents have promised to spread their message to Montana.

It should be mentioned that there is very little evidence that TransCanada’s problems were the result of not offering landowners enough money. This author has handled the negotiations with TransCanada on behalf of more than 50 landowners for the two Keystone projects in Nebraska, and the concerns of the owners always have been primarily routing, safety, permanent property damage, temporary inconvenience and money, usually in that order. At the time of this article, easements have been signed and the money paid for far more than a majority of the proposed route through Nebraska. TransCanada is still actively negotiating with owners for the remainder of the route,18 and shows no sign of backing down. TransCanada has now gone through this acquisition exercise twice, acquiring right-of-way before the presidential permit has been issued. The reason is no secret. It is a high stakes gamble. The greater the percentage of right-of-way already purchased from the people directly affected, the greater the likelihood the route will be approved, and the sooner the pipeline can be under construction.

Major pipelines have long been constructed in Nebraska and elsewhere with little thought given to potential problems encountered in obtaining the corridor easements from property owners. This is not likely to be the same in the future. While property rights have been somewhat lost in the debate, those rights sparked that debate. Almost every Nebraskan now has an opinion on whether the XL pipeline should be built, and there are many reasons for leaning either way. The most remarkable part of the process to this author is the demeanor of my fellow Nebraskans. Strongly held opinions are expressed all across the state, but with mutual respect. Rallies and public meetings are not merely peaceful, but usually even pleasant. There will always be exceptions, but it has not been uncommon for the two sides to share their soft drinks and pizza while promoting their opposing positions.

As the two sides talk, they find significant common ground. They agree that private property is important, and most agree that threats to take property by the power of eminent domain should not be issued until after all necessary permits for the project have been obtained. They agree that their state should have some say as to where a proposed pipeline will cross the state. Regardless of the outcome of the XL project, the heightened awareness created by this debate means that the winner will ultimately be the property owner. We can be assured that the agencies with the power to condemn private property will recall TransCanada and the XL project.

Why Support the XL Pipeline19

- It will create American jobs. TransCanada estimates 9,000 direct jobs nationwide and 42,000 indirect jobs.

- It will significantly increase the local tax base in the rural counties through which it passes. TransCanada estimates 17 of 27 counties will have tax base increases of 10 percent or more.

- America needs the oil. The XL will connect the Gulf Coast refining centers with the third largest oil reserves on earth and the second largest oil region in the U. S.

- Canada is our neighbor and friend.

- The XL pipeline will be the safest pipeline ever built in the U.S.

- Pipelines have a better safety record than trains and trucks. TransCanada cites studies supporting this.

- Pipelines are more efficient than trains and trucks.

- The choice for oil is either Canada or Venezuela, with the same carbon footprint.

- American oil from the Bakken in North Dakota and Montana can be transported through the XL. TransCanada expects to transport up to 100,000 barrels of crude oil per day from the Williston Basin in North Dakota and Montana.

- There are many pipelines through the Sandhills.

Why Say ‘No’ to the XL20

- The safest ever is not safe enough. Unlike conventional oil, tar sands oil will sink, rather than float.

- Spills and leaks will occur somewhere, sometime. Tar sands are more corrosive than conventional oil. They are heated to promote flow through the pipeline and are under great pressure.

- The Sandhills are too unique and fragile to be put at risk.

- The Ogallala Aquifer is one of the world’s great water supplies and cannot be risked. It is estimated that the Ogallala Aquifer supplies water to more than one-fourth of U.S. irrigation and provides drinking water for more than two million Americans.

- The reroute does not truly miss the Sandhills or the aquifer.

- A foreign corporation should not have the power to force its way through American property.

- Oil extraction from the Canadian tar sands is not environmentally sound. Opponents claim that up to 2.4 million barrels of water per day will be used to extract the oil, stored in large tailing ponds, constituting toxic sludge that will work its way into the clean water supply. Additionally, opponents list destruction of boreal forests and loss of habitat for caribou and other wildlife.

- Tar sands produce oil that is difficult and costly to refine.

- Tar sand oil refinement is not environmentally friendly. Opponents cite carbon dioxide levels of three to four times greater than conventional oil. Tar sand oil emits higher levels of sulphur dioxide and nitrous oxide.

- The cost of cleanup can be extraordinary. In 2010, one million gallons of tar sand oil poured into the Kalamazoo River. Critics estimate nearly one billion dollars have been spent on cleanup, but a large stretch of the river remains contaminated.

- The XL pipeline will create only between 50 and 100 permanent American jobs, and could kill more jobs than it creates.21

Endnotes

1. www.timetobuildkxl.com.↩

2. http://keystone-XL.com/about/environmental-responsibility/.↩

3. http://keystone-XL.com/about/the-project/.↩

4. www.pipeline101.com.↩

5. See Executive Order 13337, 65 Fed. Reg. 25299 (April 30, 2004).↩

6. Neb. Rev. Stat.§57-1101 (Reissue, 2010).↩

7. Neb. Rev. Stat. §76-704.01 (Reissue, 2009).↩

8. L.B. 1, 102nd Legislature, 1st Special Session (Neb. 2011).↩

9. Nebraska Constitution, Art. IV §20.↩

10. L.B. 1161, 102nd Legislature, 2nd Session (Neb. 2012), codified at Neb. Rev. Stat. §57-1501, et. seq. (2012 Cum. Supp.).↩

11. See Thompson v Heineman, Lancaster County, Nebraska District Court, Case No. 12-2060 (2012).↩

12. Nebraska Constitution, Art. IV §20.↩

13. Thompson v Heineman, Appeal No. 14-158, Nebraska Supreme Court.↩

14. Neb. Rev. Stat. §57-1401, et. seq. (2012 Cum. Supp.), as adopted by L.B. 1, 102nd Legislature, 1st Special Session (Neb. 2011).↩

15. Neb. Rev. Stat. §57-1101 (Reissue 2010).↩

16. See Bold Nebraska, www.boldnebraska.org/category/news.↩

17. Adams, Dirk, “Top 10 Reasons Montanans Should Oppose the Keystone XL Pipeline,” http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dirk-adams/keystone-xl-pipeline_b_4631428.html.↩

18. Verified by the author on Feb. 27, 2014, in conversation with one of TransCanada’s right-of-way agents.↩

19. Points 1–8 from TransCanada website: http://keystone-XL.com/timetobuildkxl/. Point 9 from www.transcanada.com/bakken.html.↩

20. Points 1, 2, 4 and 7–10 from Friends of Earth, “Keystone XL Pipeline,” www.foe.org/projects/climate-and-energy/tar-sands/keystone-XL- Pipeline.↩

21. The New York Times, Interview With President Obama, published July 27, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/28/us/politics/interview-with-president-obama.html. “Pipe Dreams?” Cornell University Global Labor Institute Report, January 2012.↩

Photo: Kodda/Shutterstock.com

Photo: Kodda/Shutterstock.com