Introduction

The rise in vehicle sales has brought about a recovery in the auto industry. While this has a generally positive influence on the value of the real estate from which dealers operate, the ramifications of the industry’s recovery on landlords is somewhat complex. Understanding how the boom in an industry can have negative consequences for the associated real estate is critical for property owners and those who advise them.

Auto Dealerships: How They Began, How They Work

Since the automotive industry began more than a century ago, manufacturers have focused on vehicle design, manufacturing and brand promotion. Toward that end, retail distribution is accomplished through a network of independent dealers. Dealers receive exclusive franchises for specific trade areas and act as representatives of the manufacturer to the car-buying public.[1]

Manufacturers grant franchises to dealers, without charge, and the manufacturers and dealers are, in effect, partners in the process of marketing automobiles. The franchises are not transferable, and when a dealer change occurs the parties involved negotiate a buy-sell agreement for the dealership operating company. When multiple brands are marketed, the prospective purchaser of the dealership operating company submits applications for franchises to each manufacturer, and approval is typically subject to the buyer’s demonstrating sufficient experience in the industry and having strong financial backing.

Recent Trends Affecting Auto Dealerships

Six years after the financial crisis, two trends have become evident regarding properties designed for automobile dealership use: 1) auto sales have skyrocketed, resulting in an increase in demand for the properties at which they are sold, and; 2) auto manufacturers are moving quickly towards standardizing the architecture and design at the dealerships marketing their products. The second trend is in response to the first—we will explore both.

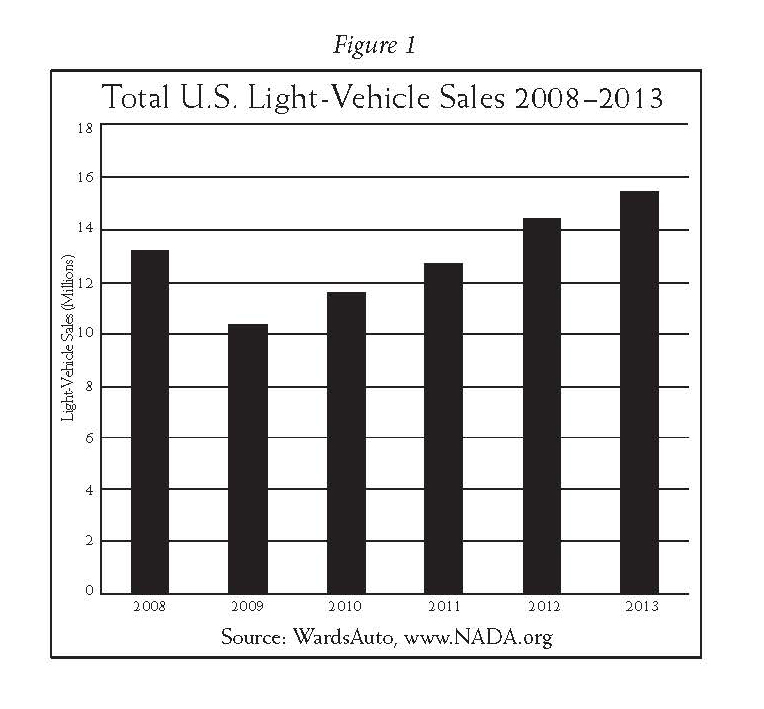

The recession and financial crisis nearly crippled the auto business, but unlike many other industries, its recovery has been robust. Volume is increasing steadily, with 2013 light-vehicle sales of 15.5 million units up 7.5 percent from 2012’s total of 14.4 million units.

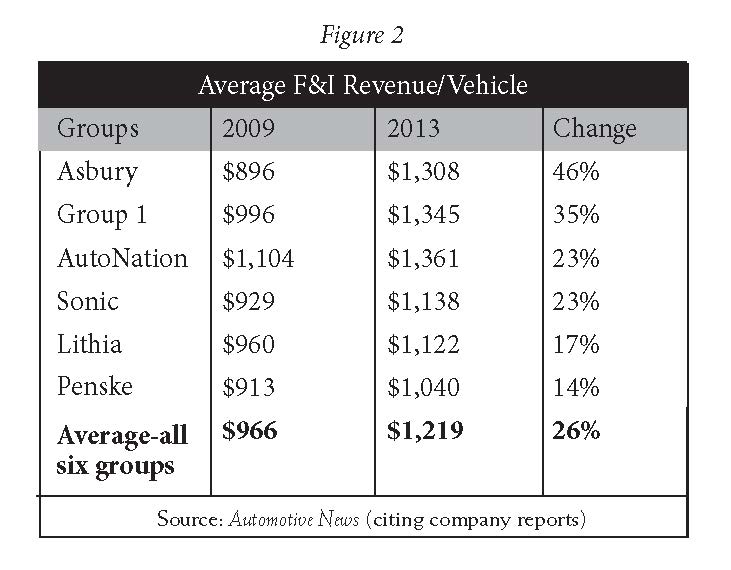

In 2013 automakers sold vehicles at higher prices with lower rebates, and higher margins coupled with increasing sales resulted in widespread prosperity. All six large publicly traded new-car dealership groups have posted higher average finance and insurance (F&I) revenue per vehicle since recording a recent low in 2009.

The average U.S. dealership produced return on equity of 29 percent in 2013, according to Automotive News (citing the National Automobile Dealers Association as its source). That figure has risen in four of the past five years, and dealerships also are now enjoying record profits.

The return to profitability, and at record levels, is a trend welcomed by auto dealership owners and operators. Good times for auto dealership businesses, though, have triggered another trend that can cause enormous losses associated with the dealership’s real estate component.

During and following the recession, manufacturers had been extremely flexible in auto dealership design standards, as few operators could afford a costly renovation. However, as a direct result of the improving finances of the dealers in their network, manufacturers are now focusing their attention on modernization and standardization of the properties that fly their flag. Manufacturers often impose costly standards, and can do so because of their enormous leverage in this situation. While franchisors having influence over a franchisee is not unique, there are some characteristics regarding the manufacturer/auto dealership relationship that are unique. The manufacturer can link the inventory it makes available to a franchisee to how willing they are to comply with requirements to make alterations to their property; and if the manufacturer is not satisfied, they can withhold the supply of the most sought-after models. The manufacturer can cancel a franchise agreement, which is a particularly intimidating prospect in markets when no other major manufacturer franchises remain. Or, if the dealer wishes to sell its business to another party, the manufacturer can withhold approval for the transfer of the franchise. Auto dealer franchise agreements typically include the manufacturer having a right of first refusal for the real estate, so the manufacturer can even insert itself into a simple sale of the dealer’s real property.

Who Decides What Makes an Auto Dealership Functional?

Generally speaking, functional utility is determined by the market. However, this truism is only partially true for automobile dealerships. In interviews with automobile dealership experts conducted in 2013 and early 2014, many expressed the opinion that the most important real estate consideration related to this specialized property type is whether the improvements are up to the manufacturer’s standard, since a dated appearance can result in the manufacturer’s requiring a “re-imaging” project. (Re-imaging is an auto industry term meaning remodeling or renovation; it can be as simple as changing the color scheme and signage, but is often more costly, and can include new finishes and design changes that require partial demolition and constructing additions.) Consequently, if a renovation has not been performed within the past several years, there is significant risk that the manufacturer will require one. While the market encourages owners of most types of real estate to keep their properties modern and up-to-date, the pressure on auto dealership owners is more direct.

In his 2000 article, “Appraising Auto Dealership Facilities,” Charles E. Tholen, ASA, presented a detailed description of typical physical requirements at that time for dealerships based on their anticipated sales volume.[2] When asked in a 2014 interview if these requirements were still appropriate, Tholen responded, “Today, the manufacturers want all their dealerships to have a similar look, just like McDonalds.”[3]

Case Studies

The shift towards modernization and standardization can be very costly. When market forces suggest it’s time to remodel, the design usually incorporates cost engineering, and a competitive bidding process is used throughout. However, when an automobile manufacturer requires a dealer to renovate, the requirements may be too stringent for significant cost engineering, and limitations regarding who does the work also could reduce or eliminate opportunities for savings. (There is a certain frugality

that is lost when standards are set by an entity that is not paying the bill.) Investment decisions that may make sense from a business standpoint can sometimes have a horrific effect from the perspective of a real estate investment. When the owner of the property is also the owner of the dealership business being operated, it is possible that incentives from the manufacturer may make a bad real estate investment worth the cost. When the dealer is a tenant, though, and the lease does not have a very long remaining term, the landlord may be forced to pay or contribute towards a renovation that pleases no one but the manufacturer…or lose the tenant.

The following case studies demonstrate how manufacturer-mandated renovations (or re-imaging projects) of automobile dealerships often play out.

Case Study #1 – Chevrolet Dealership

The Property: There are three buildings constructed from 1985 through 1998 that total 37,920 square feet; they are supported by an 11.126-acre site fronting the on-ramp of an interstate highway within a grouping (or “cluster”) of competitive dealerships. The area is in the decline stage of the real estate cycle, characterized by falling demand and rising vacancy. Median Household Income: $56,989 (five-mile radius).

The Renovation: The project required 15,941 square feet of new construction, along with partial demolition of existing structures and renovation of others. The net change in building size was an increase of 3,921 square feet. The scope of the manufacturer-mandated renovation is summarized as follows:

- A 1,540-square-foot used automobile sales office was razed in favor of additional parking;

- The office/showroom and service drop-off was razed and re-built;

- Portions of the parts area were renovated;

- 1,580 square feet of building area was added for parts delivery.

Impact: After construction, the improvements were largely concentrated in a single building, which is a more functional design. The dealership also had a newer, more modern appearance. The effective age of the improvements was reduced from approximately 23 years to ten years.

Cost Budget: $2,945,184

Financial Viability Considerations: Construction projects are considered financially viable if the increase in income (or value) is sufficient to justify the cost. Factors influencing the financial viability of this renovation and expansion included:

- The local market area was at the decline stage of the real estate cycle, which is usually not a good time for new construction projects;

- The renovated property was only 3,921 square feet larger than prior to construction, and most of the building area was still second-generation (albeit renovated) space;

- Many of the areas demolished had not reached the end of their economic life, meaning that they were razed while still contributing value;

- While the project resulted in the property having a more efficient layout and a newer, more modern appearance, it was generally functional prior to construction as well; further, even after construction it still did not have a new appearance or completely modern design.

Indications of Feasibility: The following indications were considered in assessing the project’s financial feasibility:

- The value of the real estate prior to construction was $3,300,000. Adding the expansion/renovation cost of $2,945,184 resulted in the basis of the renovated property being $6,245,184, or $149.26/SF of building area (based on its size after expansion) Market comparables consistently showed lower prices, suggesting that it may be advantageous for the current occupant to sell this property (or vacate if it were the tenant) and relocate to one of similar utility and appeal that is available at a lower cost.

- Using a market capitalization rate of 9.00 percent indicates that net income of $13.43/SF would need to be achieved to justify an investment of $149.26/SF ($149.26 x .09 = $13.43); assuming vacancy and collection loss of five percent, an absolute net rental rate of $14.14/SF would be needed to achieve this level of net income ($13.43 ÷ 0.95). Market rent comparables were materially lower than this feasibility threshold.

- While constructing a property similar to this dealership either before the renovation or after may have been financially feasible, converting the property from its original design to what would conform to the manufacturer’s requirements was not. The high cost of this project was evident when comparing it with the cost to construct a similar property new. The renovation budget of $2,945,184 is only slightly less than the cost of a new building; however, the renovated and expanded building still had a relatively advanced effective age, and lacked the appeal of brand new construction. The high cost is likely attributed to the inefficiency often associated with modifying an existing property, requirements by the factory that did not lend themselves to significant cost engineering, and restraints imposed on who did the work and what materials could be used.

Return on Investment: Prior to construction, the property was valued at $3,300,000, and after construction it was valued at $4,250,000; therefore, the contribution to value made by the renovation and expansion was $950,000 ($4,250,000 – $3,300,000). By comparison, the investment required to achieve this $950,000 increase in value was $2,945,184. Business considerations may have motivated the dealer to comply with the manufacturer’s requirements; however, from a real estate perspective, the project resulted in a significant loss. Consider the following indications from this investment:

- Profit From Construction: Negative $1,995,184 ($950,000 – $2,945,184);

- Return on Investment: Negative 68% (-$1,995,184 ÷ $2,945,184);

- Recapture of Investment: $0.32 on the dollar of capital investment was recovered ($950,000 ÷ $2,945,184).

Conclusion and Relevance: A real estate project not initiated by market forces can result in a big loss from a real estate investment perspective. However, an auto dealership operator seeking to retain its franchise may still proceed if the business considerations outweigh the real estate considerations. If a landlord is leasing an auto dealership property to such a franchisee, it may end up being the one with the difficult choice; pay for a renovation project that will not enhance the property’s value enough to justify its cost, or watch its auto dealer tenant build its own facility elsewhere or find another existing dealership property that costs less to modernize. When an automobile manufacturer require its franchisees to renovate their property, the results outlined above are not unusual.

Case Study #2 – Cadillac and Buick Dealership

The Property: Nine buildings constructed from 1976 through 1984 that total 141,034 square feet are scattered throughout a 24.15-acre site. The property fronts a heavily traveled, four-lane roadway near a regional mall. The area is in the recovery stage of the real estate cycle, characterized by rising demand and decreasing vacancy. Median Household Income: $51,374 (five-mile radius).

The Renovation: A renovation was recently completed at a cost of $862,747. However, Cadillac and Buick GMC required a second phase, as a result of a new image deployed by General Motors. The scope of the second phase of the renovation is summarized as follows:

- The Capital Buick GMC Showroom and an office building were gutted, completely reconstructing the interior with finishes required by the manufacturer;

- The front portions of the Capital Cadillac Showroom/ Office and Service Building were demolished and rebuilt;

- The angular floor plan of the showroom and office were replaced with a more “boxy” floor plan;

- A customer service area with customer drive-through bays was added;

- Site repairs were made, including resurfacing the asphalt paving at the front of the site at “customer touch point” areas;

- New signage was added.

Impact: Prior to the renovation, the property suffered from significant functional challenges: it is inordinately large for its market; the improvements are in multiple buildings that are some distance from each other, with some areas serving redundant functions; the large amount of parking exceeds the requirements of this market (while this is advantageous, it is not beneficial enough to justify its cost given high land prices in the area). After the renovation the property was more attractive with a modern appearance. However, all of its design flaws remained. The effective age of the improvements was reduced from approximately 25 years to 20 years.

Cost Budget: $4,399,281 (for the second phase of renovation being required)

Financial Viability Considerations: The renovation reflects specific requirements by the manufacturer, some of which were high-end, costly finishes. Significant capital was invested to get the dealership to look more like others under the same flag; little was done to resolve its functional issues.

Indications of Feasibility: The following indications were considered in assessing the project’s financial feasibility:

- The real estate was valued at $13,500,000 prior to construction, and at $15,500,000 after renovation, indicating that the contributory value of this construction is $2,000,000. The cost of the renovation was much higher at $4,399,281, indicating that renovating the property is not financially feasible.

Return on Investment: The $2,000,000 contribution to value made by the renovation and expansion ($15,500,000-$13,500,000) was much less than the budgeted cost of $4,399,281.

- Profit From Construction: Negative $2,399,281 ($2,000,000 – $4,399,281)

- Return on Investment: Negative 55% (-$2,399,281 ÷ $4,399,281)

- Recapture of Investment: $0.45 on the dollar of capital investment was recovered ($2,000,000 ÷ $4,399,281)

Conclusion and Relevance: Despite the property’s good location and enhanced post-renovation condition, this construction project was grossly infeasible. A large part of the reason for this is that, atypical of most high-budget renovation projects, even after renovation the property still suffered from significant functionality and design issues, as the manufacturer required improvements only to aesthetics and finishes. While the franchisee may have received discounts and incentives from the manufacturer to help recoup some of the construction costs, a landlord paying for such a renovation would not likely recoup this investment unless the costs were amortized through a lease (and that lease was honored).

Summary of Case Studies

The case studies presented demonstrate that automobile dealership renovations can cost far more than they contribute to the value of the real estate. Therefore, a franchisee that owns the real estate from which it operates must be very careful to ensure that the factory’s incentives are sufficient to offset its loss. However, when a dealership is leased, who pays for the renovation is a matter of negotiation. When the tenant has viable alternatives, such as building a new facility or relocating to an existing property in the same trade area, the landlord can be at a decided disadvantage in the negotiation. And, as explained below, while a tenant facing a renovation cost that rivals that of new construction has little to lose, a landlord has plenty to lose if its out-of-date dealership property is vacated.

What to Do If the Tenant Leaves?

When a tenant vacates an auto dealership, whether or not it was related to capital improvements required by the factory, ramifications to the landlord can be far more serious than for landlords of conventional property types. There are a limited number of manufacturers, and as discussed earlier, each grants their dealers an exclusive territory; therefore, there is a finite number of auto dealerships that can operate in a given area. Markets with the greatest demand can be the worst place to lose a tenant because another manufacturer relationship simply might not be available.

As shown in the case studies, re-imaging can be costly, and rarely generates a positive return to the real estate. While all dealerships have some chance of being subjected to a manufacturer-required renovation, the risk associated with an application to establish a new franchise is enormous. If a landlord cannot come to terms with an auto dealership tenant about how to handle the cost of a factory-mandated re-imaging, it seems unlikely it can escape major construction by simply finding a different tenant, as any new tenant would also be an applicant for a new franchise. Dealerships that suffer from an outdated appearance or antiquated design eventually reach the end of their economic life, meaning that continuing this use is no longer economically practical. While that day may come for all dealerships, it is often best to postpone it as long as possible. Given their singular use—to sell vehicles—and specific design requirements, automobile dealerships do not lend themselves well to conversion. Auto dealerships historically had been viewed as prime candidates for alternative uses because they generally have large sites with good commercial locations. However, the large supply of dealerships that became vacant in the years following the recession and financial crisis gave property owners and their advisers a first-hand lesson on how rare it is for a re-adaptive use to actually make financial sense for a failed dealership.

Conclusion

Landlords who own an automobile dealership property that has not been renovated or re-imaged within the past several years find themselves at significant risk. Making matters worse, since auto dealership operators require a manufacturer to grant them an exclusive territory, these tenants can be hard to replace. Many auto dealerships are owned by REITs or large private groups who generally understand these risks. However, there also are many dealerships owned by individuals and smaller groups. Further, sudden improvement in profitability is also drawing a significant number of investors who are new to this industry, and who may not understand its nuances. Issues specific to the automotive industry should be understood and analyzed by investors contemplating entering the market for these special-use properties, as well as by the counselors that advise them.

Endnotes

1. Charles E. Tholen, ASA, “Appraising Auto Dealership Facilities,” Valuation 2000 Papers and Proceedings, p. 81.

2. Ibid., p. 86

3. Charles E. Tholen, ASA, January 2014 email conversation