Remote working is still upending the office property sector. In an article I wrote for Real Estate Issues in 2021, I considered the early evidence that working from home and hybrid work arrangements were likely to be lasting legacies of the pandemic.1 Two years later, the “will they or won’t they return to the office“ debate is largely settled: workers won’t be sitting at their company desks nearly as often as before the pandemic – and firms won’t be occupying nearly as much space.

After reviewing the emerging new dynamics of office leasing, I focus in this article on the impact that reduced office tenant demand on property capital markets. Already property values have fallen more in the office sector than in any other property sector, while investment returns have been the lowest. And that pain will only intensify as market conditions weaken further.

But as with the shakeout in the retail sector, outcomes for individual owners and buildings will be highly differentiated. The premier buildings – those with the best locations, designs, amenities, and services, and especially health and safety features – will prosper with high occupancies and record rents. Much of the commodity “B” space will continue to muddle along.

But many other buildings in the middle will see a dramatic reversal of fortune, including some formerly Class “A” offices that until recently commanded premium rents. This is where we can expect to see the greatest concentration of distress and value destruction.

A Radical Decline in Office Market Demand

It all centers around tenant demand. The office property market was flourishing on the eve of the pandemic. Occupied space, rents, sales transactions volumes, and sales prices were all posting record levels, while vacancy rates had fallen to their lowest level since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). That all changed abruptly with the COVID lockdown in March 2020. Firms sent their employees home, and many quickly shed excess space where they could.

Still, the financial damage was relatively contained, given the magnitude of the economic downturn and job losses and the immediate spike in idle office space as most former office workers started to work from home. The national office vacancy rate rose less than 200 basis points in 2020 – far less than the change in actual office usage.2

The impact was muted for several reasons. First, most firms initially didn’t want to give up their valuable office space because they believed they would soon be back in the workplace. Few executives imagined that remote working would take root and endure after the economy reopened. Also, office-inclined sectors generally sustained fewer layoffs than most other sectors – and some, like tech, actually grew sharply – giving firms less incentive to reduce their workspace.

Most importantly, tenants cannot just walk away from their leases, even if they physically abandon their workplaces. Office space is typically leased for five or more years, and firms generally can only relinquish those obligations via bankruptcy (or negotiation). Office vacancies can surge in a recession when many firms file for Chapter 11, but the COVID recession was notably different. Few firms went bankrupt as generous government relief programs kept them solvent. Thus, most office tenants could only exit their leases once their lease period ended.

So, the market descent has been slowed but not averted. Vacancies continue to rise as leases expire and firms shrink their office footprint. A small number of firms have given up their offices entirely. Many more have been simply cutting back their space commitments.

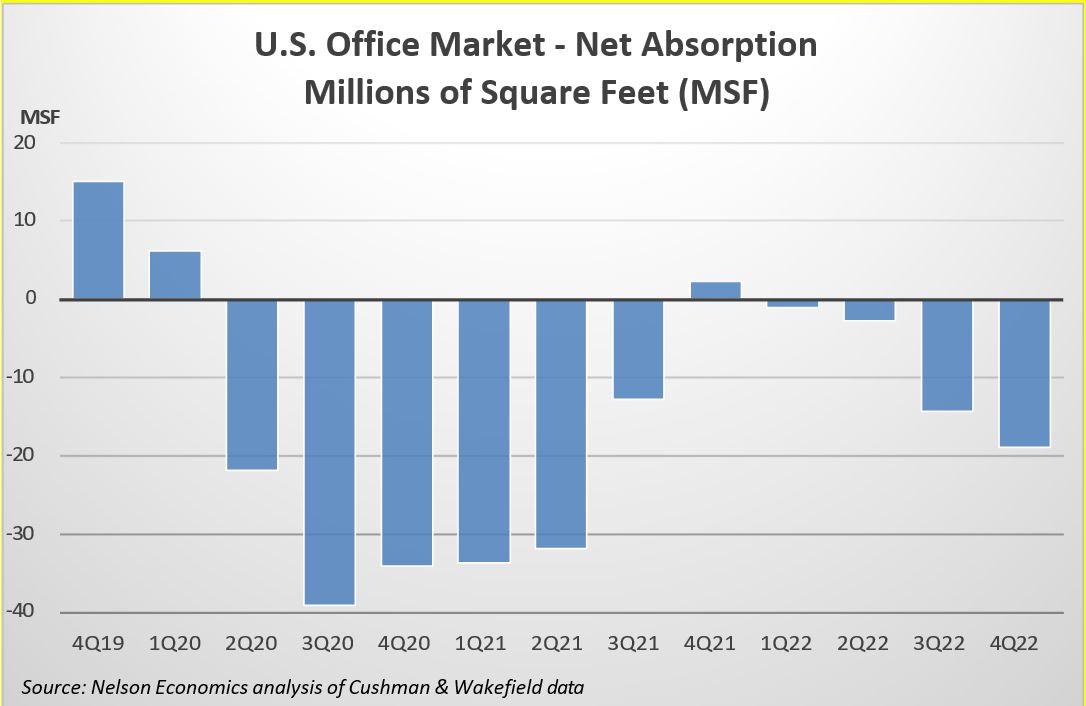

Overall, net absorption has declined in ten out of the last eleven quarters (through the end of 2022) as firms give back more space than they lease. A year ago, a modest office market recovery seemed to be in sight. Though few tenants were signing new leases and fewer still were increasing their commitments, more firms began to renew leases for at least a portion of their old space. But that pickup proved short-lived. Net absorption has turned increasingly negative in each of the last four quarters, despite record employment in the office-inclined sectors.

In the roughly 60 markets tracked by Collier International, total space under lease now is some 200 million square feet less than when the pandemic began. Together with some 100 million square feet of new deliveries, the amount of vacant space has jumped by 40% in three years. The office vacancy rate has risen over 400 basis points to 15.7%, the largest increase in any property sector since 2019.3

A Smaller Corporate Footprint

For now, the vacancy rate remains below its GFC peak, but all signs suggest that vacancies will continue rising in the coming quarters to reach record levels as tenants give up more space than they lease. JLL Research reports that quarterly gross leasing activity in the U.S. has dropped 30% in the last two years (2021-22) compared to the four years preceding the pandemic, from 60 million square feet per quarter to just 42 million.

More important, tenants are still actively shedding excess space as their leases expire. The best indication of future leasing intentions is the amount of unused space firms are making available for sublease. Colliers estimates that sublease availability has doubled from pre-pandemic levels to almost 250 million square feet. For perspective, that’s nearly 70% more than at the peak of the GFC. Most of that space will eventually be counted as vacant landlord space once the leases roll from the tenants’ responsibility. Thus, expect vacancy rates to spike over the next two years unless firms abruptly begin to lease more space than they have been.

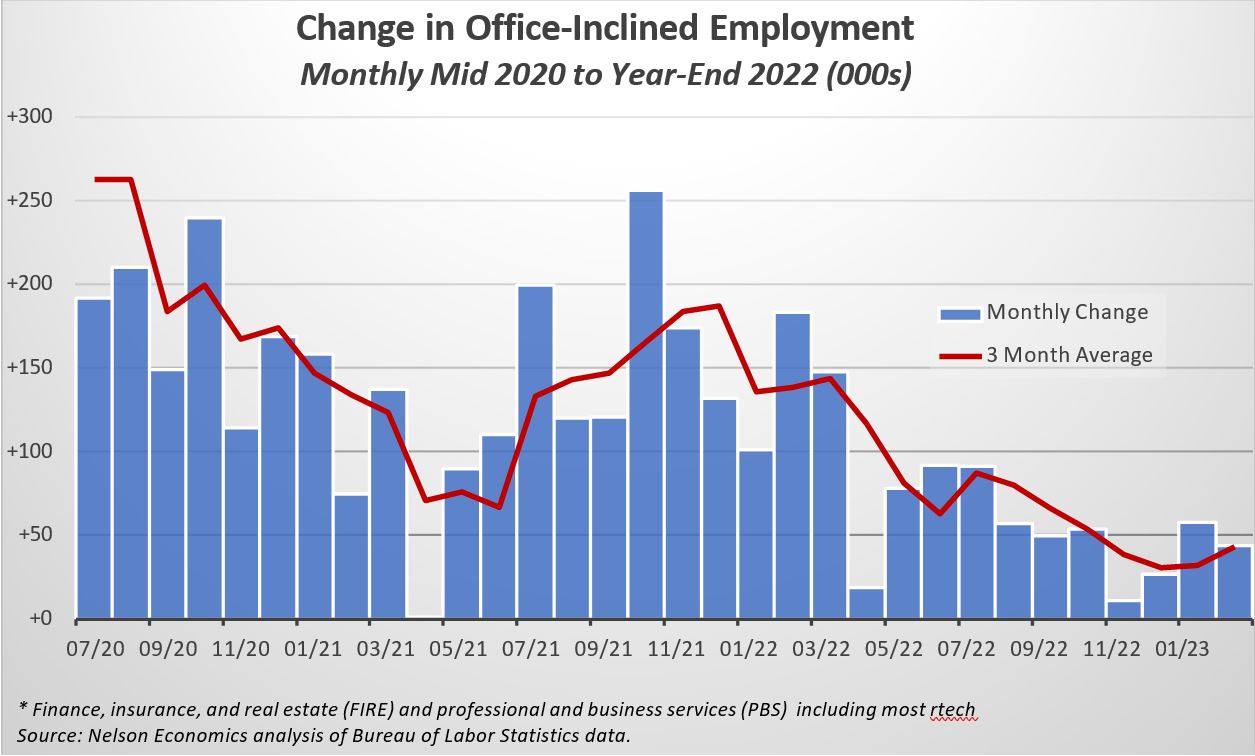

But that seems improbable for both cyclical and structural reasons. First, the economic cycle will not be favorable for office markets for some time. Job growth is normally the single biggest driver of office demand, especially the knowledge jobs in finance, technology, and professional services typically based in offices. Yet leasing has languished in recent quarters despite continual, if declining, gains in office- type jobs – 34 straight months and counting since the lockdown. Employment in these office- inclined sectors is 5% greater now than on the eve of the pandemic, but the amount of leased office space is down more than 1%.

Though economists still debate the likelihood of the U.S. economy entering a recession this year or next, few expect job growth to accelerate. Despite stronger-than-expected job growth reports so far this year, we can expect growth to slow or eventually reverse as the Fed clamps down on inflation and slows the economy by raising interest rates and shrinking its balance sheet.

For now, layoffs remain moderate. However, the tech sector, which fueled an outsized share of office leasing in recent years, is pruning many of the jobs it added during the pandemic. Already almost 500 tech firms have announced nearly 140,000 layoffs in 2023, on top of 160,000 job cuts announced last year.4 At typical tech office densities, that translates into erasing 50 million square feet of space demand.

Of course, these cyclical layoffs, and those that could come in a recession, might prove transitory. Then hiring in the next cycle should eventually support new office demand once the economy again begins to expand. But evolving work patterns mean that employment, at whatever levels, will translate into less office space demand than it used to.

Remote Work Changes Everything

What’s changed? Remote working, obviously. COVID not only reduced the number of people working in employer-provided offices but also induced firms to rethink their workplace strategies and recalibrate their space needs. Most of us will not be working in an office as much as we did in the “before times,” and it’s just too expensive for firms to keep paying for idle space. To be sure, there is a wide range of opinions on how much firms will ultimately cut back, but there is little doubt that the dynamics driving office space demand have shifted, if not permanently, then at least indefinitely.

Where are we now? Surveys conducted by WFH Research show that “days worked from home are stabilizing at near 30%,” up from only about 5% of paid workdays prior to the pandemic – a sixfold increase.5 That’s for all U.S. workers. Remote working rates for office workers are even higher because knowledge work is more transportable than factory and warehouse jobs, for example. Precise figures for office workers are elusive and vary by market, but several different sources tell a similar story.

Kastle Systems estimates that in major markets, only half as many office workers are at their desks on a typical day compared to pre-COVID levels, though these figures vary widely by market.6 However, many experts dispute these widely cited figures, which are based on the number of keycard swipes in a sample of the buildings Kastle serves. Some landlords use their own security systems or other measures and report higher attendance.

An analysis of Placer.ai data cell phone location data in 250 Manhattan office buildings released by the Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) reported that “average building visitation rates in 2022 surpassed 60% of pre-pandemic baselines,” considerably above the Kastle’s New York figures.7 This discrepancy is likely explained by differences in the submarkets and building quality sampled by each source. But even the more positive REBNY data still show attendance some 40% below pre-COVID levels – hardly a sign of a return to the old normal.

On the other hand, Avison Young finds even lower return-to-office rates than Kastle, using cell phone tracking data in 45 metros. AY estimates that attendance in December 2022 was just 42% of December 2019 levels.8 To be sure, all sources show return-to-work rates continuing to inch up. But regardless of the precise figures, there is little doubt that office usage is still much reduced from pre-pandemic levels, more than three years after the pandemic began.

How Much Space Demand?

The paramount question is whether workers will eventually return to the office often enough for firms to justify returning to their former leasing patterns. Logic and available evidence suggest otherwise. Few workers enjoy the isolation of working at home all the time, but surveys show that the vast majority do appreciate the benefits of more flexible work arrangements. Workers also save money by not commuting, such as spending on transit and parking, dining out, and dry cleaning.

And their employers have learned to accept remote working. While some managers lament the loss of control when workers are out of the office, they’ve learned that many workers can be just as productive working at home, so long as they come into the office regularly to collaborate with colleagues.9 Another benefit to firms: many employees end up working longer hours when not commuting. A recent study shows that remote workers in the U.S. save an average of 55 minutes in commuting time per day and devote nearly half of that time savings to their job – a win-win for employees and their employers.10

But the most important reason firms are reducing their footprint comes down to basic real estate economics: Office space is expensive, particularly in major markets. Occupancy costs tend to be the second largest expense after payroll. Firms just cannot ignore the substantial cost savings to be realized with an effective hybrid workplace strategy.

As a result, there is a growing recognition that the dynamics driving office space demand have shifted away from assuming the resumption of old work patterns. For a while, many firms assumed that employees would naturally return to the office once COVID retreated. But they didn’t come back after the first wave waned, nor after the second, despite growing employer mandates to return that went largely unheeded. Workers have similarly ignored subsequent calls for them to return.

Some analysts speculate that the economic slowdown will finally be the factor that spurs workers back to the office as a weaker labor market tilts the balance of power back to employers. That may be wishful thinking. After three years of working remotely, hybrid work remains a valued benefit that workers will not easily surrender. Numerous surveys show most workers do not want to – and will not – return to the workplace full-time.11 This is particularly true for highly-valued knowledge employees who, before the pandemic, normally worked in downtown office buildings most days. Moreover, firms and workers alike have invested too much effort and capital figuring out how to work efficiently from home offices.

With most workers coming into the office less often – and some not at all – firms will be looking to reduce their occupancy costs to more closely reflect actual office usage. But firms will not be able to reduce their space commitments commensurate with the share of workdays worked remotely. Some workers will demand dedicated offices or cubicles even if they come in only three or four days a week – though this amenity can be an obvious point of negotiation with their employers in exchange for remote working privileges. And most workers in a hybrid scheme will come to the office on the same days to facilitate collaboration and team building – or just long weekends. Thus, firms will need to provide enough space for the maximum usage days.

In sum, office demand will decline, but not as much as office usage. A consensus view is emerging that demand will decrease by some 15% relative to pre-COVID trends, that is, for a given level of employment.12 But the decline will not be uniform across markets and buildings. As overall office demand recedes, it is also changing in two crucial ways: the location and the type of space demanded. Each presents a significant shift from pre-pandemic trends.

Geographic Demand Shifts

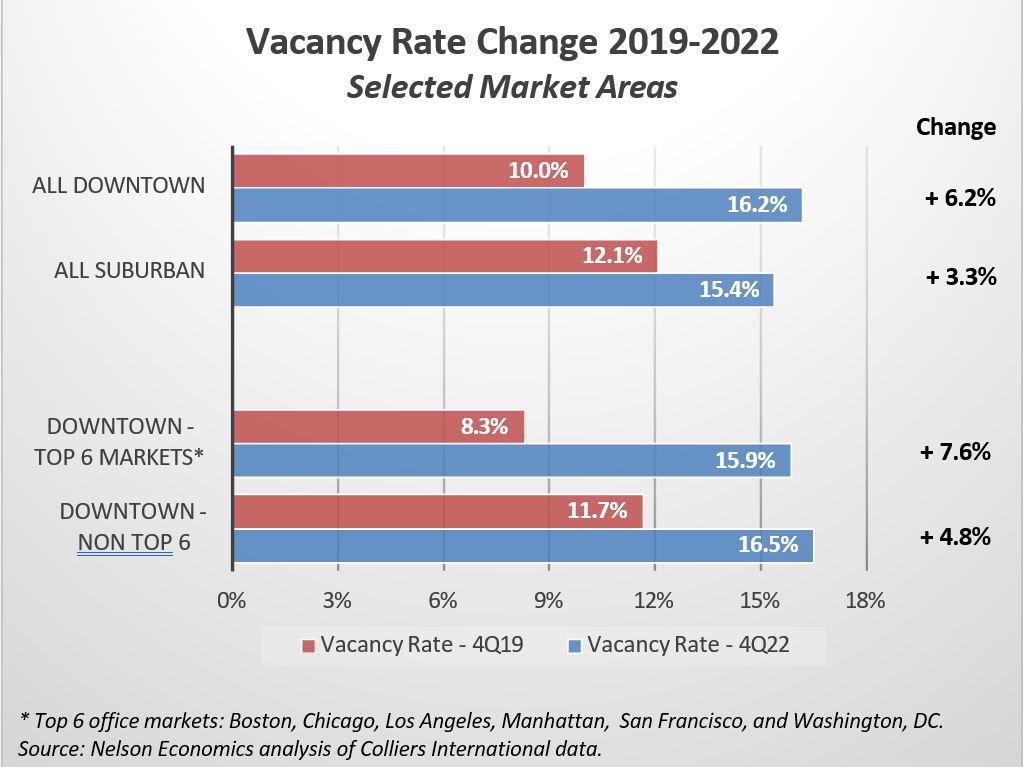

In a stunning reversal of fortune, office demand is shifting away from downtown markets, especially in the dominant office markets. On the eve of the pandemic, most downtown markets were outperforming their suburban counterparts, as they have been for the last two decades. The average vacancy rate was 10% at the end of 2019, more than 200 bps below the suburban average.

That changed dramatically during the pandemic, however, as vacancies rose higher and faster in downtown markets than in suburban markets. Three years later, suburban vacancies stand 80 bps below the downtown average as the vacancy rate jumped 620 basis points (bps) in downtown markets versus just 330 bps in suburban markets. This shift is the opposite of what usually occurs after market downturns, when tenants leverage falling rents to trade up from commodity suburban space to more desirable downtown offices.

Perhaps even more remarkable is the change in the nation’s pre-eminent office markets. Almost half of the nation’s downtown office space is located in just six markets: New York, Chicago, Washington, San Francisco, Boston, and Los Angeles (in declining size order). These markets historically have also been among the tightest markets in the country, commanding some of the highest rents. But the pandemic has dented their hegemony. Vacancy rates in these top downtown markets have soared 760 bps since 2019 compared to 480 in all other downtown markets – and again, just 330 bps in suburban markets.

What’s going on here? Firms and their workers are fleeing these top markets, and downtowns generally, both because they can and because their high costs give them more incentive to leave. Dense central cities saw significant residential out-migration in the early days of the pandemic. That has largely reversed, and apartment occupancies are generally back to pre-COVID levels or higher. But not downtown offices.

For one thing, the primary office markets tend to be highly concentrated in the sectors most conducive to remote working, like tech and professional services. So, these jobs are more portable than most.

But it is the higher cost structure in these markets that is the primary driver for firms to reduce their footprints and for workers to work remotely more often if they can. Rent for Class A space in the top six markets on average is more than twice that in the rest of the nation, increasing the potential savings from cutting workspace.

Meanwhile, transit costs and commuting time are also greater in these markets, providing workers more incentive to work from home more often. Finally, these are some of the most expensive housing markets in the country, pushing office-liberated digital nomads to move to more affordable markets, whether in the same metro further from the city center or even to another region.

Tenants Trade Up

It would be erroneous to conclude from these geographic trends that tenants are abandoning premium office space altogether, however. On the contrary, there is a striking flight to quality. But unlike the typical pattern where firms seek out better workplaces at a bargain as rents fall during a market downturn, now tenants are often paying records rents to be in the absolute best space.

Firms realize that to attract workers back into the office, they must be viewed as doing everything possible to provide a safe and comfortable work environment. With fewer private offices, the workplace also must be designed to facilitate collaboration. Firms are also under growing pressure to report and improve their Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) records, and so seek out buildings with superior ESG ratings.

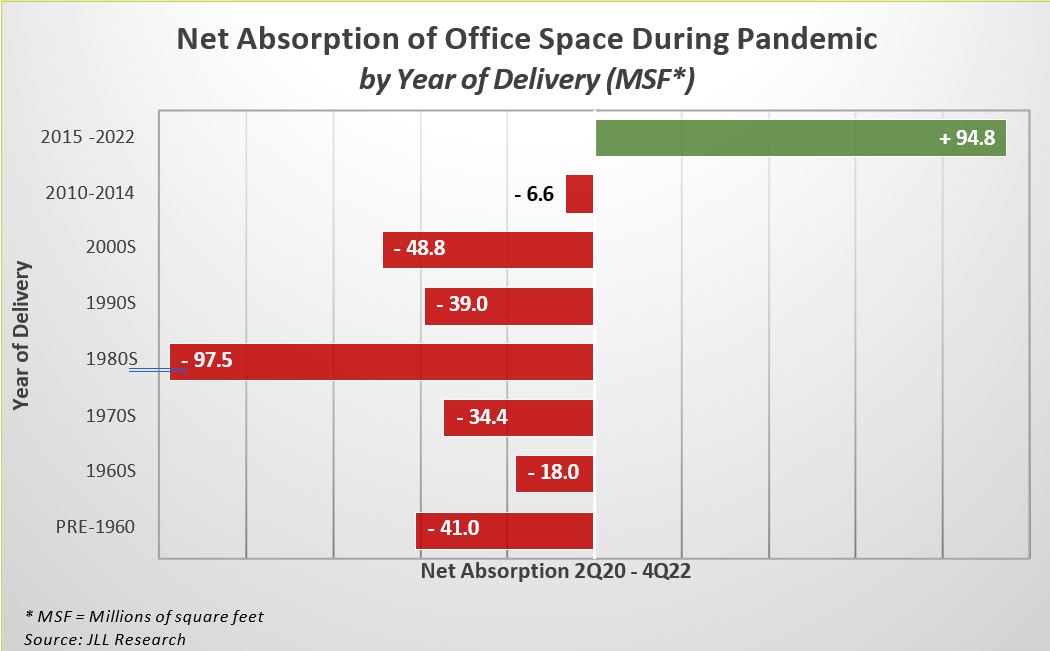

Thus, tenants increasingly favor new buildings with modern building systems, designs, and amenities, while avoiding just about everything else. In addition to demanding premium health features like efficient HVAC systems with rapid air-refresh rates for the COVID era, tenants expect floor-to-ceiling window lines and high ceilings to maximize natural light as well as sustainable designs that minimize the building’s carbon footprint. Older buildings lacking these features cannot compete for the corporate tenants that account for much of the office leasing.

These tenant preferences are reflected in leasing data compiled by JLL Research stratified by year of building construction. Net absorption during the pandemic has been strongly positive for buildings completed since 2014, while every other construction vintage has been mildly to significantly negative, particularly the glut of buildings constructed in the 1980s.

Thus, the pandemic has prompted seismic shifts in what kinds of space tenants seek and where. The traditional leading markets are lagging as tenant demand shifts to other markets, while many Class “A” buildings go begging for tenants if they cannot upgrade to the new standards.

Higher Cap Rates Yield Negative Returns and Falling Values

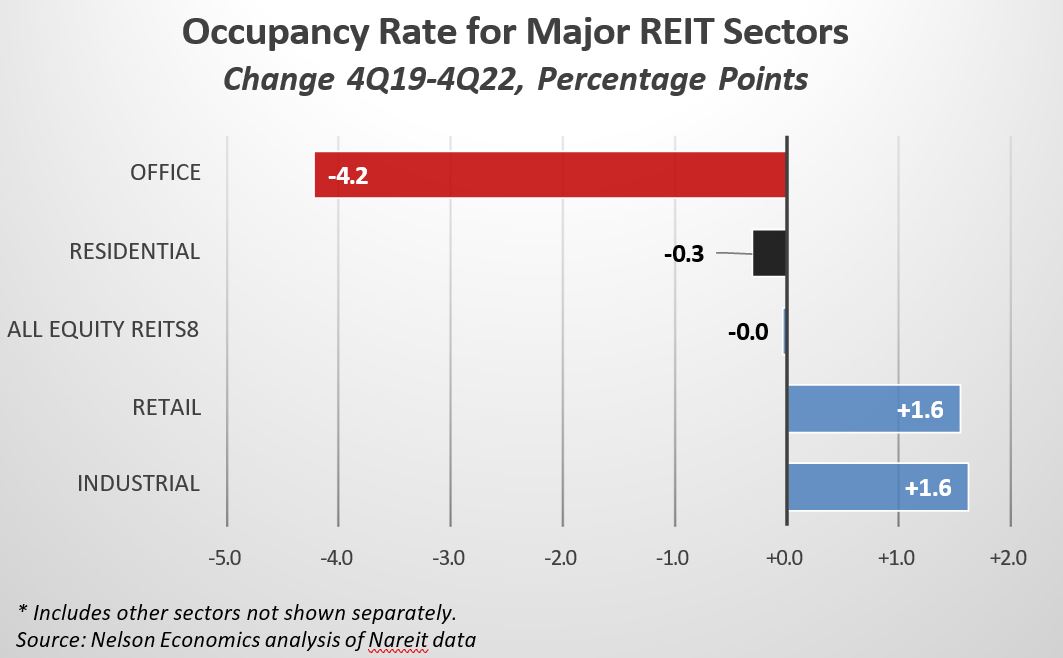

Thus far, the impact on office property income has been limited – despite the falling occupancy. Occupancy across all office REITs, for example, has dropped far more than in any other property sector since the end of 2019. By contrast, REIT occupancy rates overall have been flat: about the same now as before the pandemic.

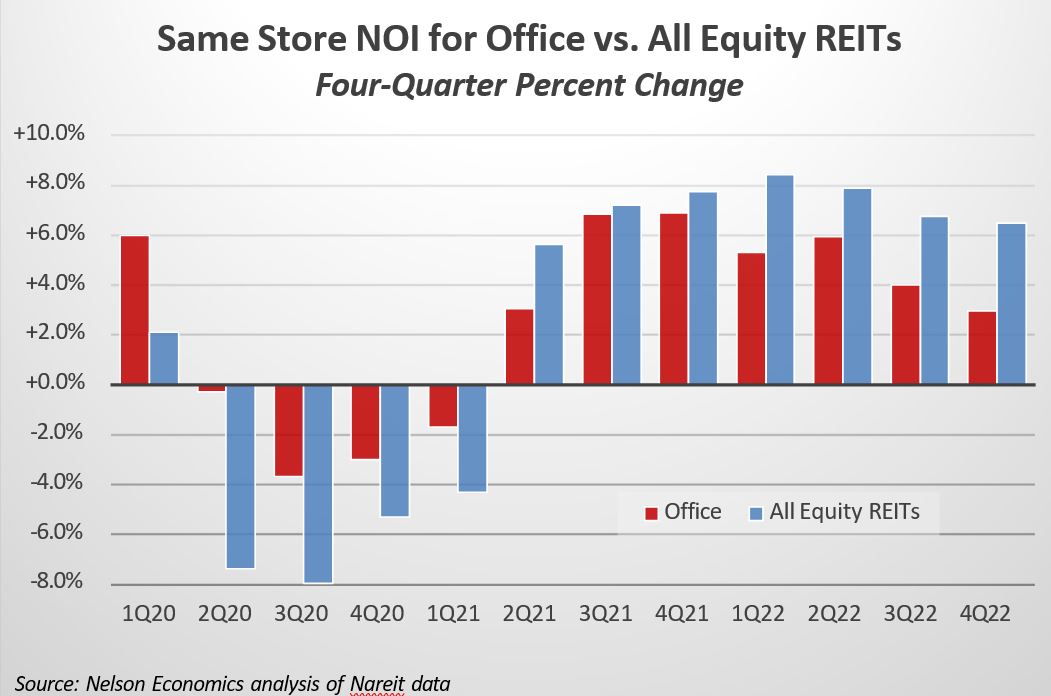

Even with the rise in office vacancies, revenue in office REITs has continued to increase during the last two years, though less than for REITs in other property sectors. Most office leases contain rent and expense escalation clauses, often tied to inflation rates, so net operating income (NOI) can rise even as occupancy falls, particularly during times of elevated inflation, as we have now. Measured by four- quarter percent change – roughly equivalent to annualized growth – office REITs have enjoyed seven straight quarters of rising “same-store” NOI, controlling for changes in building inventory.

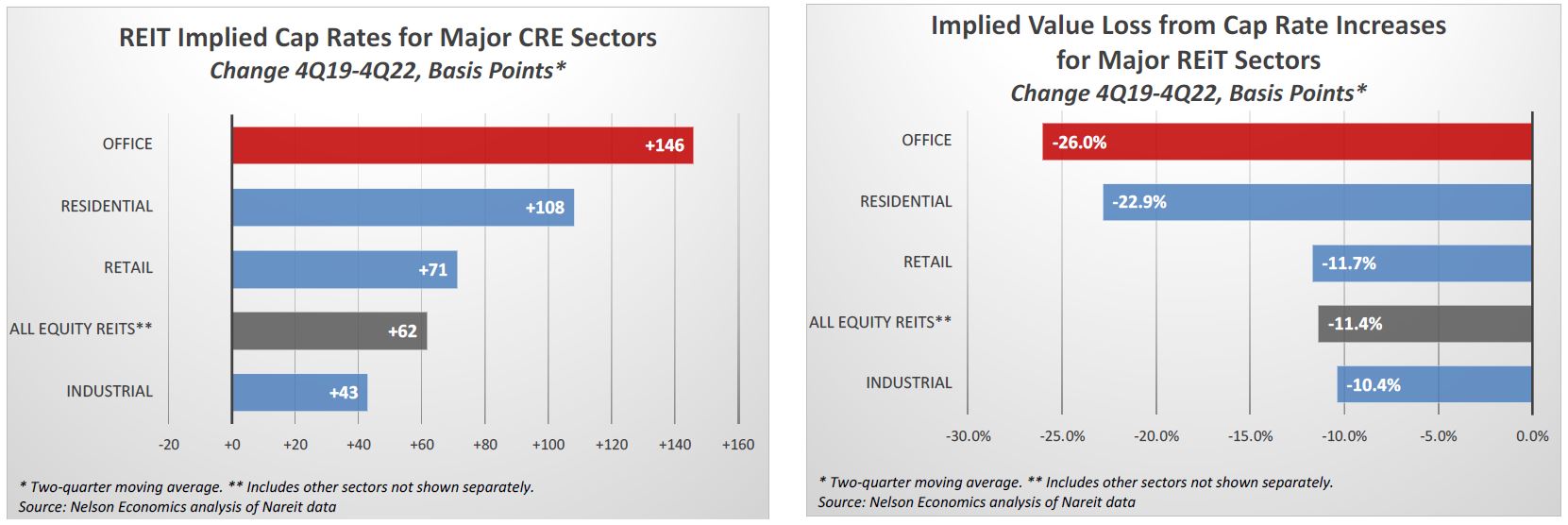

But office NOI will soon begin to falter as old leases expire, vacancies rise, and rent levels for non- premium space fall. Investors’ loss of confidence in future office income streams is undoubtedly what is driving down investment returns and values. Income capitalization rates have been rising for all major property sectors but have increased the most for offices relative to pre-COVID rates. The cap rate movement alone is equivalent to a 26% decrease in value – again, more than any major property sector and twice the implied 11% value decline in the index for all REITs.

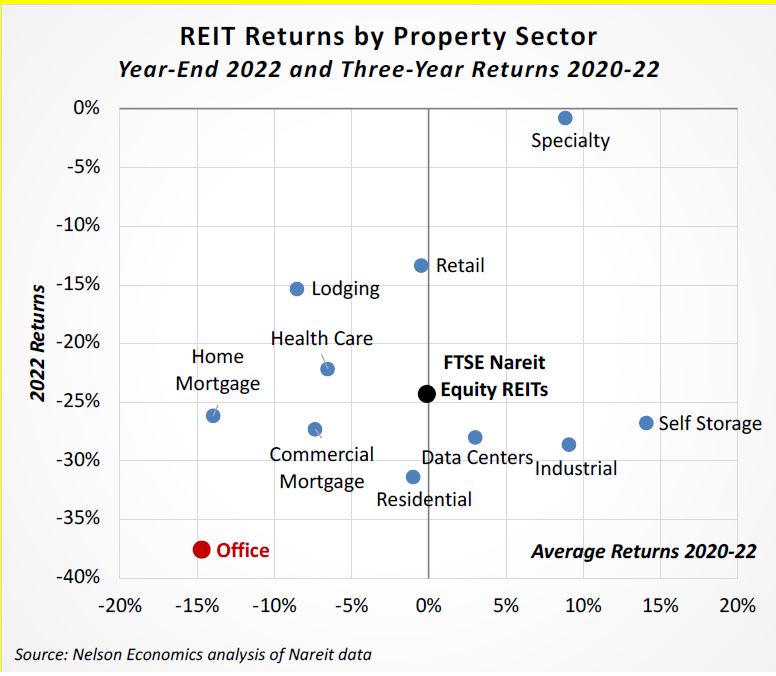

These value declines are driving down investment returns. Rising interest rates have hit all returns across all property sectors. But office REITs have been the worst-performing property sector tracked by the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts (Nareit) both in 2022 and cumulatively for the three years since COVID hit. Last year office REITs generated returns of -37%, underperforming the REIT industry by almost 13 pps, as measured by the FTSE Nareit Equity REITs Index (FNER). Only two of 22 office REITs in the index beat the all-sector FNER index in 2022, showing that the challenges facing the office sector are not limited to one type or market.

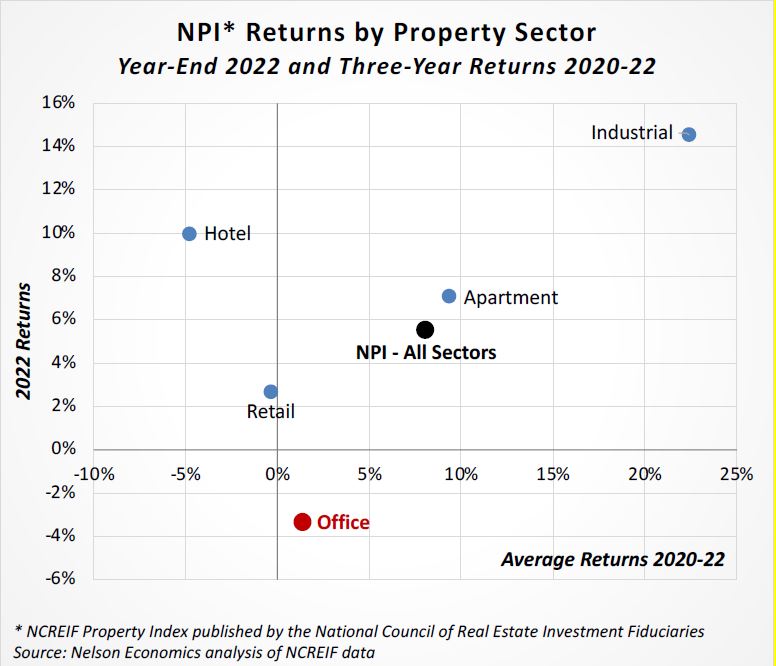

Office returns are also lagging in the private real estate markets, though the losses have been more moderate and gradual due to “appraisal lag” and less volatile pricing dynamics. The National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF), which tracks investment returns by institutional investors like pension funds and other large private investors, reports that the office sector was the only major property sector with negative returns in 2022, underperforming the industry by almost nine points. Last year was no aberration. Since the pandemic started, cumulative office returns have been 80% below the industry average as measured by the NCREIF Property Index (NPI).

Capital Markets Bifurcate, Too

Investors are following the shifts in tenant preferences: paying up for the best quality space in the desired markets – and even investing in new construction – while avoiding just about everything else. Office deal volume fell 25% in 2022, the most of any primary property type, according to MSCI, which covers all deals over $2.5 million. Owners and buyers cannot agree on pricing, so a lot of capital has moved to the sidelines. With owners not yet willing to accept value losses unless forced to sell, bid-ask spreads for most potential sales are too wide to bridge. That’s causing the apparent paradox of rising average sales prices despite deteriorating office market fundamentals because the deals getting done are weighted toward premium product.

But that capitulation is starting as owners face the dual and compounding threats of maturing debt and tenant lease expirations. Industry sources such as Trepp and the Mortgage Bankers Association estimate that a quarter of all commercial mortgages will be maturing in the next two years, much of that in offices. Many landlords are facing the prospect of needing to re-up their financing at much higher interest rates at the same time as their tenants are leaving or will re-lease at only lower rents. Even if they want to see it through, some owners will have trouble meeting operating covenants for debt coverage and occupancy levels, and thus may not be able to retain their existing debt or secure new financing. Complicating matters, recent banking woes are reducing the pool of potential lenders.

The project economics just won’t make sense for many owners. While higher debt costs and lower rental income will strain operating revenue, landlords will need to invest additional capital to retain or attract tenants. Tenant improvement allowances are growing as firms seek to create more collaborative workplaces. Plus, many buildings require system upgrades in order to compete in the COVID era – even buildings that had been considered Class “A” before the pandemic. Thus, changing tenant requirements are rendering more buildings functionally obsolete as potential revenue cannot support the enormous costs to renovate them to modern standards.

As a result, a growing number of owners are being forced to sell at distressed prices or simply give back the keys to their lenders. Already this year, Vornado, RXR, Columbia Property Trust, Brookfield, GFP Real Estate, and other major property owners have either defaulted on office-backed loans or announced they are walking away from office portfolios. Many more undoubtedly will follow, and the costs will be enormous as the market distress will accelerate value declines, further reducing returns on office REITs and institutional office portfolios.

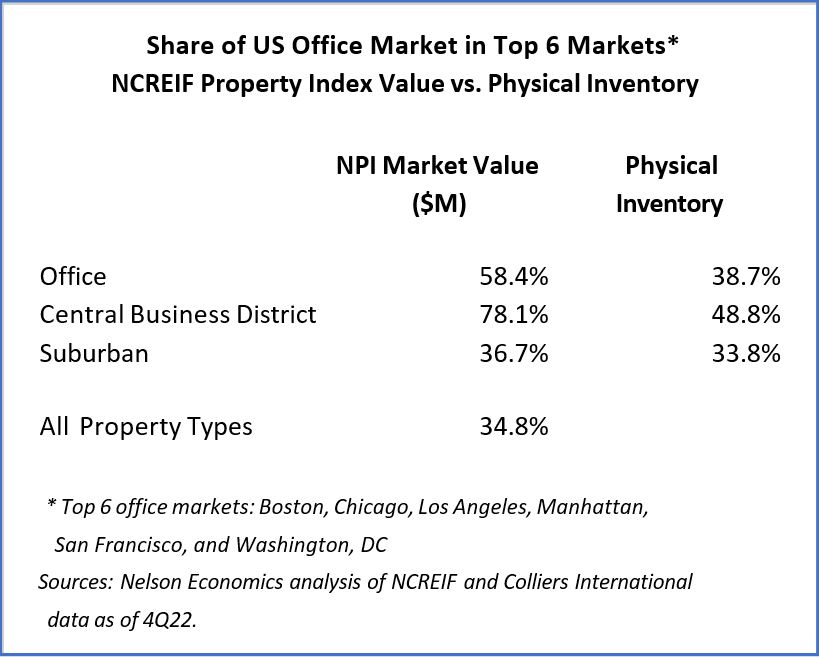

This impending wave of foreclosures and distressed sales will hit major office investors hard because their holdings are disproportionately concentrated in the very markets likely to be most impacted by reduced space demand. For example, the top six office markets in the country have just under 40% of the nation’s office stock as measured by building area. But these markets account for almost 60% of the office assets in NCREIF’s Property Index (NPI) and more than three-quarters of the office value in the nation’s Central Business Districts (CBDs).

Of course, one investor’s distress is another’s opportunity. From this perspective, the evolving market dynamics will offer enterprising investors many compelling opportunities. But for current owners – and their lenders – this year will be a time of careful consideration and weighing through difficult choices. Office tenants adapted to remote working. Office investors are next.

ENDNOTES

[1] “Office is the New Retail: A Dynamic Property Sector Faces Painful Adjustments and a Bifurcated Recovery,” Real Estate Issues, Volume 45, Number 9, May 28, 2021. https://cre.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Real-Estate- Issues-Office-is-the-New-Retail.pdf

[2] U.S. Office Market Outlook, Q42019 and Q42020, Colliers International.

[3] U.S. Office Market Outlook, Q42019 and Q42022, Colliers International.

[4] Layoffs.fyi, accessed on March 16, 2023. https://layoffs.fyi/

[5] SWAA March 2023 Updates, WFH Research.https://wfhresearch.com/wp- content/uploads/2023/03/WFHResearch_updates_March2023.pdf

[6] Kastle Systems Back To Work Barometer and 10-City Daily Analysis, March 6 2023. https://www.kastle.com/safety-wellness/getting-america-back-to-work/?_hsmi=249130406&_hsenc=p2ANqtz– JkyyJhoUKjiAH9-cDV6o-R13e_4ebKtrUcrm-MP18XYK191hDouxLEvUCPsJmJJUkteZJ6HCe8mM- 4WlRyXHotqNOjEzB4OYPFXKOQY–P20utW0#workplace-barometer

[7] “New REBNY Analysis of Manhattan Office Visits Shows Increasing Activity, Particularly in Certain Segments of the Market,” Real Estate Board of New York, February 27, 2023. https://www.rebny.com/press-release/new-rebny- analysis-of-manhattan-office-visits-shows-increasing-activity/

[8] Q4 2022 U.S. office market overview, Avison Young. https://www.avisonyoung.us/us-office-market-overview

[9] “Work-From-Anywhere: The Productivity Effects of Geographic Flexibility, ”Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper No. 19-054. Last revised: 13 Aug 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3494473#

[10] “Time Savings When Working from Home,” Cevat Giray Aksoy et al, National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2023. http://www.nber.org/papers/w30866

[11] See, for example, “Returning to the Office: The Current, Preferred and Future State of Remote Work,” Gallup. August 31, 2022. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/397751/returning-office-current-preferred-future-state- remote-work.aspx

[12] “Office: The Long Shadow of Covid,” Green Street. https://www.greenstreet.com/insights/blog/global-office- the-long-shadow-of-covid

@israelandrxde/unsplash.com

@israelandrxde/unsplash.com