The coronavirus has seized the global economy. With the number of confirmed cases globally and in the U.S. growing by about one-third per day – that is, doubling every three days – a broad range of economic activity is rapidly shutting down, either by fiat or collapsing consumer demand, dramatically compounding the supply chain disruption that began last month. A near-term recession now seems to be a virtual certainty – both globally and in the U.S. – if we’re not in one already. This is all coming as the economy was slowing anyway, particularly in Europe.

The questions that remain are the unknowns at the onset of any recession: how deep, how long, and how widespread? The most recent signs are worrying indeed with cascading events that suggest that the downturn may well precipitate a full-blown financial crisis.

But with the unprecedented pace of events and scale of governmental responses to this pandemic, projecting economic conditions would be folly: forecasting models are simply not designed to capture this scenario. Much will depend on how widely and quickly COVID-19 spreads; the success of governmental efforts to contain and address the contagion; and the ability of central banks and governments to counteract the economic devastation and bolster confidence.

Rather than offering precise forecasts that are rendered obsolete almost as soon as they are written, the goal of this article is to provide some perspective on how the economic shutdown (shutdown!) may affect different segments of the commercial real estate sector, both near-term and longer-term. Suffice it to say, with so much that is uncertain and even unknowable at this point, the best course of action for most market participants is to defer major decisions until there is greater clarity as to market directions.

The Economic Context

The U.S. economy almost certainly is entering a recession, with enormous job losses and reduction of economic output. Direct impacts include massive hits to already weakened trade flows and even greater and unprecedented cuts in demand for a vast array of services, including almost all forms of entertainment, travel, and leisure, which together account for over 10% of GDP.1 Knock-on impacts in related sectors that support these industries or depend on their trade will magnify the impacts by one to two times the direct impact.2

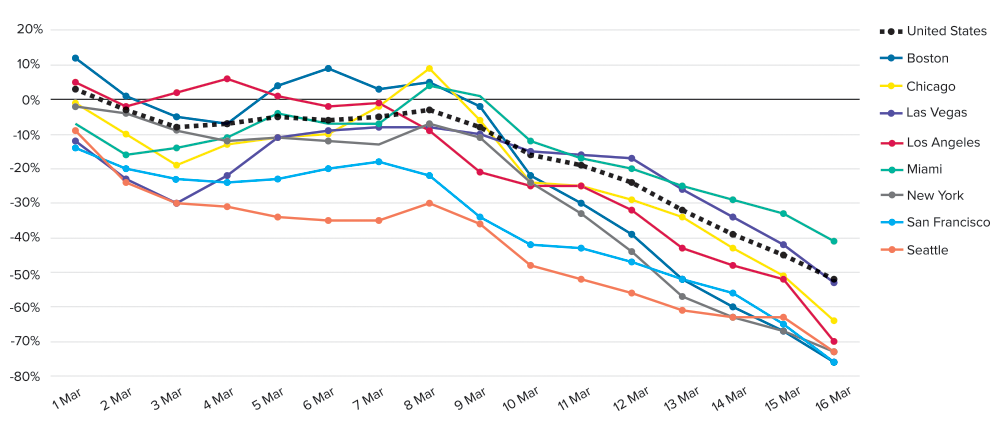

As I write this in mid-March, events are moving so quickly, and impacts are multiplying with such frightening, unprecedented force, the data normally observed to track economic and market trends are just not available yet. But here’s one dataset that demonstrates the utter collapse of demand in the food service sector: The number of diners at restaurants served by OpenTable was down 50% year-over-year – even before the local shutdowns – and the drop-off in key cities was even greater.3 With the restaurant industry generating more than $850 billion in sales last year and employing 10% of the U.S. population,4 this is the very picture of an economy in freefall.

OpenTable Seated Diners – Selected Cities – March 2020

Year-over-year Percent Change (Two-Day Moving Average)

Sources: OpenTable, compiled by Nelson Economics

The petroleum sector will also see a huge revenue decline from the fall in oil prices that helped trigger the economic meltdown, with a further drop inevitable as demand from transportation and factories plunges, precipitating a cut to production. Oil prices are now down almost 50% in just the last ten days to levels last seen in 2002.5 While positive for consumers and manufacturers, the collapse in prices will be devastating to oil producers and oil-producing regions like Texas, North Dakota, and Oklahoma.

Second-order impacts will be potentially even larger, as an expected plunge in business and consumer confidence will undercut the willingness of businesses and consumers to continue investing and spending. The coming surge in worker layoffs will only amplify the collapse in spending, which accounts for more than two-thirds of GDP. Already, leading employers in the airline and hospitality industries are planning enormous layoffs, while more than 50 major retailers – with names like Apple, Nike, Footlocker, and Chico’s, are temporarily closing stores globally.6 The earliest data on jobless claims suggest unemployment could quickly surge beyond the 10% peak reached in the Great Financial Crisis (“GFC”).7

A related concern is the wealth effect associated with the rapid drop in the value of almost all financial assets. A recent study shows that a dollar rise in equity wealth is associated with a 3.2 cent increase in spending.8 Less well understood is how much spending drops when wealth declines rapidly, but we can expect a significant reduction given the 30%+ plunge in equity values in the last month.

Finally, supply chain impacts will cripple industrial output as critical inputs cannot be obtained from either domestic or especially offshore sources. In sum, virtually every segment of the economy looks to be hurt, many badly. Given all these cascading challenges, forecasters keep revising even their downside scenarios ever lower. At this point, even this week’s forecast by Goldman Sachs of a 5% drop in second-quarter GDP might prove to be optimistic.9 Expect one of the sharpest economic contractions on record.

Ultimately the depth and length of the recession – and whether it turns into a depression – will depend on whether the downturn precipitates a financial crisis in which liquidity is strained and financial institutions, businesses, and households cannot satisfy financial obligations. Liquidity is already being tested, as extreme drawdowns on corporate lines of credit last week, needed to offset revenue shortfalls, diverted funds in the banking sector available to finance other parts of the economy. Fortunately, the Federal Reserve has the experience it gained in the GFC and has been able to step in with unprecedented speed to lower rates (- 150 bps) and restart Quantitative Easing in order to ensure liquidity and otherwise reassure markets.

That likelihood of another financial crisis cannot be determined until the magnitude of the pandemic and effectiveness of the government response are better understood. The severity of the recession should be tempered by the low interest rates and the regulatory guardrails adopted after the GFC. Moreover, the speed and scale of the Fed and federal government’s (belated) response are encouraging. However, record levels of corporate debt have replaced the high household debt levels preceding the GFC, setting the stage for a surge in bankruptcies if the downturn/shutdown continues for long.

Likewise, the question of how quickly and robustly the economy snaps back after the shutdown – whether the recovery is “V” shaped or “U” shaped (quick or protracted) – also will depend on the extent of financial distress caused by the shutdown. While many large corporations may be able to quickly re-hire furloughed or laid-off workers, many small businesses may not survive the shutdown, dampening and delaying any potential bounce back.

Impacts on the Commercial Real Estate Sector

After a historically long if subdued property cycle, commercial real estate is set for a major hit. At least during the shutdown period, we can expect both leasing and sales transactions to fall sharply and prices and rent levels could follow, depending on the length of the downturn. Occupiers and investors alike will want to defer decisions for as long as possible.

Property Markets: Near-Term

The near-term impacts on property fundamentals will be greatest on the commercial real estate sectors that house the businesses most subject to the shutdown. At the top of the list are travel-related uses and those most dependent on social gatherings. Hotels, restaurants and bars, theaters and performing arts centers were all already seeing a devastating fall in patronage, even before the closures were mandated.

Then, as in any recession, impacts will be felt by the land uses with the shortest guaranteed tenancy periods such as hotels (again) and parking lots, which must re-lease their space daily. Both can expect a severe plunge in revenue and surge in vacancies. Apartments are typically the next major land use to experience falling demand. With most tenants renting either month-to-month or annually, vacancies can rise quickly as tenants start to lose their jobs or otherwise lose income.

Retail, office, and industrial (in that order) all typically have longer-term leases that blunt immediate impacts, though vacancies will still rise as expiring leases are not renewed. Vacancies will then mount when bankruptcies start to swell. In this regard, the already reeling retail sector can expect yet another wave of vacancies, particularly in weaker centers in secondary markets. Most critically, retail will be hurt as services – restaurants and other food service, health clubs, massage – have been among the lone sources of strength in recent years but will be especially hit by the shutdown. After the surge in panic buying of essentials, we can also expect a sharp decline in retail sales, particularly for discretionary goods, as workers lose their jobs and consumers save more and hunker down.

Though warehouses and logistics facilities are vulnerable to the supply-chain and trade disruptions, the sector is relatively protected by the longest average lease terms, as well as secular changes shifting space demand from the retail to the industrial sector.

More vulnerable is the flex-office space segment, where most occupiers have only monthly commitments. As this niche product was growing in recent years, analysts debated whether demand would be sustained in a recession: While corporations may increase their use of flex-space to house workers or new divisions without taking on longer-term commitments, start-ups and sole proprietors may go back to their garages or second bedrooms. This debate did not envision the social distancing mandate brought on by COVID-19, which should dramatically reduce flex-space demand during the shutdown. However, outside of flex office space, the office sector will be initially shielded by its relatively long lease terms and the restrained construction in most markets during this cycle.

Also vulnerable in the very near term are two demographically-favored niches that have been the darling of investors: student housing and senior housing. Student housing especially is likely to see financial strains as college campuses are closed and students are sent home. And senior housing may see a short-term drop in demand as vulnerable older Americans shelter-in-place to reduce the likelihood of contracting the virus. However, both should see a rapid snap back in demand as the crisis eases.

On the other hand, healthcare could actually see a rise in leasing, potentially filling vacated retail spaces, as healthcare providers seek smaller, more localized alternatives to hospitals and large medical facilities.

Property Markets: Longer-Term

Once the recovery begins – in a few weeks or months or next year – the property sector is hardly likely to revert to pre-recession conditions. Profound shifts in how we consume goods and space are being intensified by our response to COVID-19. Most obviously, the shift from in-store shopping to e-commerce will get another big boost as social distancing forces even more goods to be purchased online. Even the fledgling food-delivery segment, which seemed on the verge of failure, will get a new lease on life as restaurants shift from onsite dining to home delivery. No doubt much of this new shift will prove temporary, especially in the food-service segment, but we can expect at least some of the shift to become permanent, as more consumers become more comfortable with online ordering and home delivery, hastening the demise of weaker retailers and compounding the sector’s woeful oversupply.

These shifts will continue to benefit the industrial property sector, particularly logistics and last-mile facilities, as retailers and manufacturers deliver goods directly to consumers at home. After a short drop-off in leasing during the shutdown, expect a rapid bounce back. Not all facilities will benefit equally, however. The pandemic has laid bare the risks to producers associated with global supply chains. Expect the nascent trend to “near-shoring” to gather strength in favor of more localized suppliers. Thus, we may see some shift from port-focused warehousing to those closer to domestic manufacturing centers.

Finally, we might also anticipate a sharp and permanent shift to telecommuting, to the long-term detriment of traditional office leasing. The joke about telecommuting is that it has a great future – and always will. Projections of shifts to working at home have long exceeded reality, even as technology has enabled distance working and outsourcing has reduced office space provided by employers. However, with firms suddenly forced to work remotely due to COVID-19, millions of workers – especially, but not exclusively, in office-based industries – are getting their first real taste of working from home, while their employers are crash testing full-scale virtual workplaces.

As with the food-delivery model, much of this shift will be transitory. There are myriad reasons we bring together workers under one roof. But some of the shift will prove permanent as firms learn to work remotely and are making material investments in telecommuting infrastructure to ensure their business can succeed with at least some of their employees working remotely. Thus, expect firms to continue the long-term trend of reducing the amount of office space leased per worker. One beneficiary should be flex-office space, as workers needing quiet space outside of the home seek affordable workplaces near-by.

Capital Markets

U.S. property capital markets were surprisingly strong on the eve of the coronavirus pandemic. Sales volumes in 2019 did fall 2%, according to Real Capital Analytics, but only because entity sales plunged 87%.10 Sales of individual property assets (+6%) and property portfolios (+28%) collectively rose 11% to $561 billion, the greatest volume since RCA began tracking sales in 2001 – and fully 10% greater than the prior high-water mark set in 2015.

But that was then. It’s way too early to know exactly how much COVID-19 will impact investor demand for U.S. property, but there’s no doubt that sales volumes will drop this year, if only due to the practicalities of getting deals done. Purchases by offshore investors were the first to slump, as buyers could not travel internationally to conduct property inspections or complete due diligence.

Now the hurdles have spread to title agents and recording offices, whose workers are being sent home, leaving pending deals up in the air. While some functions can be completed remotely, others require in-person signatures, all but ensuring that many transactions will not close for some time.

Beyond these purely physical challenges of deal making, the larger issue concerns the sustainability of investor demand for U.S. property, both domestic and offshore. Property sales volumes tend to be more volatile than leasing or the underlying economy, plunging during recessions and surging during recovery. As recently as last month – which seems like a century ago – brokers and analysts were still reporting strong demand for U.S. property for its compelling risk-adjusted returns, and a safe-haven for offshore investors.

Very early anecdotal evidence suggests a chill is hitting commercial real estate.11 Price declines seem inevitable. The most that one can say now is that markets will want more clarity before proceeding with any major decisions, so the already record stockpile of dry power will remain on the sidelines for a while longer. In the meantime, investors will be revisiting their strategies. But when the dust clears, the status of the U.S. as a safe haven should be retained or even enhanced, ensuring renewed investor demand for commercial real estate assets.

Lending will face some of the same documentation challenges facing sales transactions, though record-low interest rates and expiring loans should keep demand high. The Mortgage Bankers Association already was predicting a banner year for lending among traditional lender categories.12 With mortgage rates falling sharply since the beginning of the year, demand for refinancing should keep lending volumes strong once some of the market uncertainty eases, even if property acquisitions take longer to recover. However, with unemployment surging and corporate balance sheets strained, many borrowers may not have the creditworthiness to take advantage of the low rates.

Of course, there will be variation among the different types of lenders, with the greatest uncertainty among the so-called alternative lenders, whose activity has been relatively opaque. Much of this lending funds construction and other investments that are harder to finance. Importantly, leverage in this segment tends to be greater, with higher loan-to-value ratios, making them riskier during sharp downturns like we are starting to experience. But even more so than with other segments of commercial real estate, it is much too soon to know how activity in this segment will adjust in response to rapidly changing market conditions. This segment merits close watching for signs of distress.

Perhaps the best news on the financing front is that leverage rates overall tend to be much lower now than was the case at the onset of the GFC. Moreover, construction in most markets has been more moderate in this cycle than is typical, yielding strong property fundamentals with record low vacancy rates, despite relatively modest space take-up. Thus, depending on the severity of the downturn, defaults and bankruptcies may be less likely this time around as most financed properties have more fiscal room to absorb revenue declines.

Closing Thoughts

This is uncharted territory, with the worst pandemic in over a century spreading at warp speed in a very interconnected world. Shockingly, some health experts expect between 40% and 70% of the world’s population to contract the virus over the next year or so, of whom some 20% will develop moderate to severe health problems (or worse).

In turn, the resulting economic downturn is spreading at unprecedented speed and breadth, as both consumers and businesses sharply reduce almost all forms of economic activity, compounded by government responses to contain or at least slow the spread. Incomes are plunging and job losses are surging. So, we’re entering a recession.

How long and how deep? Certainly, much of the spending being lost now will be gone forever: the restaurant meals foregone, the theatre tickets unsold, the vacations not taken. And there will be a permanent loss of income as layoffs mount and bankruptcies rise. This recession will be more than just a temporary disruption.

Yet some spending should revive relatively quickly, once factories restart, stores reopen, and planes resume normal schedules. But the policy response matters. First, governments must contain this virus. Singapore and South Korea both demonstrated that smart, decisive action can quickly “flatten the curve” of transmissions, limiting both the spread of the disease and its impact on the economy.

Governments also must act quickly and decisively to protect vulnerable households and businesses to minimize knock-on impacts and ensure the recession does not metastasize into a full-blown financial crisis. After a belated response, the federal government is springing into action with sorely-missed bipartisan support, with a proposed $1 trillion aid package proposed on top of more direct assistance to the reeling health care sector, which may backstop some of the most vulnerable parts of the economy. And fortunately, our economy is much stronger in most respects and less burdened now than it was at the onset of the GFC, which should limit the damage.

Likewise for the commercial property sector. Save for the ailing retail sector, commercial real estate enters this recession much stronger than a decade ago. Without the degree of overbuilding and overfinancing we experienced in the last cycle, markets were able to improve steadily over the past decade, and most now enjoy record occupancy, rents, and values.

To be sure, commercial real estate owners and service providers can expect some challenging times this year (and maybe into next) as the economic downturn works its way through property markets. However, unlike with the GFC, the property sector does not look likely to contribute significantly to this downturn, and nor should it bear the brunt of the recession. But much is unknown at this early stage, and market participants would be wise to be patient and defer significant decisions until great clarity emerges on the extent of the pandemic and its impact on the economy.

This is going to be ugly. And we won’t know for a while just how ugly or for how long. Too much is happening with unprecedented speed and breath that it is impossible to gauge the extent of the escalating downturn, much less predict conditions three months out.

Perhaps the best that can be said at this very early stage is that the U.S. economy – and commercial real estate markets generally – enter this very challenging period in relatively strong shape, and the federal government and Fed are mobilizing quickly to forestall a financial crisis and limit the damage to the economy. We’ll know soon whether their efforts prove successful.

Endnotes

1. Bureau of Economic Analysis: https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_industry_gdpIndy.cfm↩

2. Economic Policy Institute: https://www.epi.org/publication/updated-employment-multipliers-for-the-u-s-economy/.↩

3. OpenTable: https://www.opentable.com/state-of-industry ↩

4. National Restaurant Association: https://restaurant.org/Downloads/PDFs/Research/SOI/2020-State-Of-The-Industry-Factbook.pdf ↩

5. Bloomberg News, March 17, 2020: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-17/oil-extends-slump-as-virus-spread-threatens-global-recession ↩

6. Business Insider, March 17, 2020: https://www.businessinsider.com/13-retailers-announce-temporarily-store-closures-to-fight-coronavirus-2020-3#chicos-8 ↩

7. New York Times, March 19, 2020: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/19/upshot/coronavirus-jobless-claims-states.html ↩

8.National Bureau of Economic Research: https://www.nber.org/papers/w25959 ↩

9. Bloomberg, March 15, 2020: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-15/goldman-sees-sharp-u-s-contraction-nber-would-label-a-recession ↩

10. Real Capital Analytics, Capital Trends: US Big Picture – 2019. ↩

11. Bisnow, March 18, 2020: https://www.bisnow.com/national/news/investment/theres-really-no-precedent-investment-appetite-plagued-by-coronavirus-uncertainty-103480 ↩

12. MBA Commercial Real Estate Finance (CREF) Forecast, January 1, 2020: https://www.mba.org/news-research-and-resources/research-and-economics/commercial/-multifamily-research/cref-forecasts ↩

Photo: ImageFlow/Shutterstock.com

Photo: ImageFlow/Shutterstock.com