Read the introduction to this series by our Publisher here.

In June of 2026, Canada’s largest city Toronto, and its third largest Vancouver, will host for the first time in this country’s history, World Cup soccer matches. Canada’s participation in this the 23rd World Cup, is unprecedented on many levels. For the first time ever three countries, an entire continent, the United States, Mexico and Canada will jointly host the tournament. The number of teams participating will be increased from 32 to 48, and the group play broken into four featuring twelve teams playing the initial round robin games. They will play in sixteen cities, including eleven in the United States, three in Mexico, and the two in Canada. As a Host Nation, Canada will play in the 2026 World Cup, only the third time they have qualified to participate.

Canada’s hosting of the World Cup is not without controversy. Its two cities will be hosting only five initial group stage matches each, with the possibility of hosting a round of 32 tie breaker matches (if necessary). Vancouver will also host one round of sixteen matches. To host these combined eleven (possibly thirteen games) in Canada is not without controversy and huge costs for the Canadian taxpayer and the two cities and their host provinces. Initially for these reasons Vancouver declined to participate in the North American bid.

Mega-cost sports events are always controversial. Proponents and beneficiaries hype financial windfalls, lasting economic and infrastructure legacies, and local and national pride. Politicians are always susceptible to this. Opponents argue the actual costs are hidden (and dwarf the benefits); that hosting such events drain funds and resources from more pressing local needs; and that these events see the political and other elites attend and benefit from the events at the expense of most everyone else. Vancouver hosted the 2010 Winter Olympics and the 2015 Women’s World Cup, generally regarded as successful but very costly events, but whose economic benefits remain questionable and undefined. As is always the case when governments and politicians promote mega events, costs are low-balled while economic spin-off benefits and revenues are always overstated to gain support for and/or justify the massive infrastructure and operating costs, while the actual and measurable post event results are often under reported and convoluted.

With an eye on an increasingly skeptical electorate, the then new Government of British Columbia announced in March 2018 that Vancouver would not be part of the joint North American 2026 World Cup bid, and purposely missed the deadline to be part of the bid book.

The British Columbia government cited both a concern about costs, and that its requests for clarification of terms and conditions by FIFA, soccer’s world governing body, were rejected. In a news release, the government’s withdrawal from the bid was unequivocal.

“While we support the prospect of hosting the World Cup, we cannot agree to terms that would put British Columbians at risk of shouldering potentially huge and unpredictable costs,” Lisa Beare, BC’s Minister of Tourism, Arts and Culture, said in a statement. Earlier this week, B.C. Premier John Horgan told reporters that while he would like to see the World Cup come to Vancouver, he was not about to write “a blank cheque” to FIFA. (Williams, Rob, “Vancouver is out of the running for the 2026 FIFA World Cup, Daily Hive, March 14, 2018.)

Vancouver, a preferred city’s withdrawal, left Toronto, Montreal and Edmonton as the Canadian cities under consideration as part of a combined North American bid. Of note is that out of 211 National Soccer Associations, the only other 2026 World Cup bidder was Morocco.

The dramatic lack of national bids, and considerable disinterest by many cities, now including Vancouver, in the clearly favoured North American bid does indicate that mega events have lost much of the luster, and that taxpayers are increasingly dubious about the benefits of staging them and that politicians and their appointed teams are not necessarily good stewards over taxpayers contributions thereof.

So why did Vancouver rejoin the North American bid and how was it successful in the end? The second part is the easier answer.

FIFA had put the 2022 World Cup in the hot desert of the Middle East country of Qatar. This country’s selection was scandalous, with clear evidence of bid rigging and bribes by and to the FIFA directors, who operate as a fiefdom. FIFA did not want to go to the hot desert again, and the North American bid would still allow them to extract funds, fees and commitments from an entire continent and sixteen cities – and in prime media centres. But with an indifferent and skeptical public, the British Columbia government still cited real concerns and valid reasons for withdrawing from the bid.

“There were concerns that security costs and the cost to install an actual grass field were not addressed. They were not conversations that took place between the province, the feds and the stadium,” said B.C. Tourism Minister Lisa Beare. “So it remains unclear.” FIFA also requires a “step-in” clause, which would allow the governing body to require host cities to make adjustments to parking, stadiums or security even after a bid has been secured. British Columbia was also concerned about a lack of indemnity for any potential cost overruns. Canada Soccer provided a guarantee for the province in the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup (held in Vancouver), that it would cover any surprise cost overruns. (Source: Zussman, Richard, “More cities follow Vancouver out the door on FIFA World Cup bid,” Global News, March 15, 2018.)

In the Spring of 2018, when British Columbia said “no” to FIFA, the then stated cost for Vancouver to host essentially preliminary World Cup Games was in the $200 million range. This was deemed too much, and the uncertainty too great. Veteran investigative journalist Andrew Jennings, whose career has been based upon exposing the excess and corruption of the Olympic Committees and FIFA tweeted his admiration for this decision and that British Columbians “should applaud their government” for not succumbing to FIFA pressure or its terms and conditions, stating:

“The FIFA contract is a laugh. You never sign it in a free world, FIFA doesn’t believe it’s a free world – they believe it’s a world run by FIFA,” said Jennings. (Source: Ibid.)

So in 2018, that should have been it. No World Cup games in Vancouver. The public was onside with this decision. But then explicitly the same government four years later, and without a logical rationale, jumped back into the bid process. And they did so without recalculating questionable and now dated budget numbers, nor comprehending the FIFA contract terms and conditions that so many other cities and countries cited for never even submitting bids – and this has been the trendline for decades. The City and Province are now on the hook for the terms and conditions in the self-serving FIFA contract – which the government has chosen not to make public (a clear indication how bad it is for the Host City) – although because the Ontario provincial government released the Toronto contract, we know that Vancouver and all have given FIFA an open cheque book and almost total control to dictate everything associated with the six, maybe seven, games – none of which are the prestigious final matches, when most of them also run in the expanded 48 team field are gone. Rather than stick with this decision, the same government had a change of heart that still has not adequately been explained, nor documented.

Toronto remains on the bid team, but two other Canadian cities, Montreal and Edmonton, declined; with the costs and uncertainty being their rationale. But then, rather than use this as further proof they acted prudently, the same provincial government that said “no,” jumped back in and now said “yes.” The Province and City of Vancouver quickly began the hype. To this end wild forecasts about the economic spinoffs overtook the narrative.

“Marquee sporting events like the FIFA World Cup 26 have the power to inspire people to get involved in sports, amplify community spirit and put a spotlight on our incredible province” said Lana Popham, Minister of Tourism, Arts, Culture and Sport. “We are excited to welcome hundreds of thousands of visitors to Vancouver and British Columbia during the World Cup to celebrate this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity with us, boost our tourism sector and economy and help secure lasting benefits for the people of B.C.” (Source: BC Place, “Province Provides Updates for FIFA World Cup 26,” News and Media, April 30, 2024.)

In March 2022, the Province estimated the TOTAL cost of planning and staging Vancouver’s games at $230 – 260 million. These were referred to as “obligations of a FIFA World Cup Host City.”

Obligation Cost – $230 million

Safety and Security – $73 million

Contingency, including inflation – $52 million

Venues – $40 million

FIFA Fan Festival – $20 million

Host City office, administration and volunteer services – $15 million

Host City decoration and brand protection obligations – $8 million

Traffic and stadium zone management and services – $14 million

Insurance – $8 million

(Source: City of Vancouver and Province of BC, News Release, March 2022.)

The City’s portion of the direct costs were to be half of this. Their plan was to introduce a further 2.5% surtax on “short term” accommodations which would pay down this debt over the decade. The City projected 269,000 visitors, of which half would be from outside North America (BC Government news release). This seems ambitious for a ten-day event. But rather than disclose, the Province began expanding the narrative and importance and benefits of these games, citing they would be a source of reconciliation with the Province’s Indigenous First Nations, and as they tried to regarding the 2010 Winter Olympics, these few games would be a perpetual economic incubator. And while the government and FIFA boosters and beneficiaries were blatantly short on details, to the point of secrecy about the costs and control over the events themselves, essentially resorting to “trust me,” this region had hosted a Winter Olympics and the 2015 Women’s World Cup and considered this quite sufficient for the time being, and knew that the promises tied to their tax dollars were not to be realized. The same public that was told its public parks, recreation facilities, cultural and community centres, and sports leagues had to do with less and a seemingly permanent decay were not in the mood to be told there were funds for a few soccer games but not their own region.

But it appears the politicians and consultants neither comprehend nor factually costed out and updated the FIFA Host City contract that was imposed on them. Toronto released their FIFA contract, but Vancouver did not. The contract language is similar. The reason for trying to hide the FIFA contract, and/or spin the many hypothetical benefits of hosting 5 – 7 preliminary soccer games became obvious. Those entrusted with negotiating with FIFA were not very good and/or had been instructed to sign away control. For decades FIFA imposed its will on cities and countries and politicians wanting to claim World Cup status. But in recent years, countries began to balk – too costly, not enough legacy benefits and far too much corruption. This is why only two 2026 bids, Morocco and the unusual North American option were the only two in the running. Citizens seem quite content to watch games on a screen. And, without paying to host them.

Canada will play its role as a 2026 World Cup host in June of that year. Both Toronto and Vancouver are each “guaranteed” five opening stage matches. In Vancouver, the games will be played June 13 – 26, with one more round of sixteen matches for sure. The Canadian games will be played as follows:

| 2026 World Cup: Canadian Venues | ||

| Toronto | Vancouver | |

| Stadium | Toronto Stadium | BC Place Stadium |

| Year Built | 2007 | 1983 |

| Capacity | 45,000 | 54,000 |

| Turf | Grass to be installed | Grass to be installed |

| World Cup Matches | · 5 Group Stage Matches

· Round of 32 Tie |

· 5 Group Stage Matches

· Round of 32 Tie · Round of 16 Match |

As it stands, now, late 2024, the cost to stage the Vancouver World Cup games went from around $230 million to $531 million, and rising. And no one who has reviewed the FIFA contract and history thinks it stops here. The FIFA contract is one-sided and FIFA has an override throughout. Everything, everything, is to be done (and paid by the Host City) to FIFA standards – up to and through the Games. It is the proverbial blank cheque – and FIFA will cash it.

So the pattern of mega event madness continues here in the Pacific Northwest. The pattern is predictable. Politicians and those few who benefit directly from others paying for it, get seduced by the hype and themselves being “players.” Next the costs are ridiculously underestimated, as benefits are overestimated, such as Vancouver Mayor Ken Sims claiming that his City’s 5 – 7 World Cup games – none of which are close to the final stages, are the equivalent to “30-40 Super Bowls.” Really?

And then when the actual costs and consequences of the event are revealed, the narrative changes to “world class” cities have to stage such events. And in the end, factual and verifiable debriefings and cost-benefit analysis are not objectively done, if at all.

Currently, British Columbias have given FIFA and their own politicians a “red card” for the imposition on their province and taxes. No doubt many enjoy watching the World Cup, and there is optimism that the Canadian team, who play twice in Vancouver, will do well. But by wide margins, the polls indicate the final costs, – still unknown are not worth it – by far. Like the 2010 Winter Olympics and the 2015 Women’s World Cup, the events are nice, but the actual legacy benefits never seem to materialize, and real priorities and needs are sacrificed.

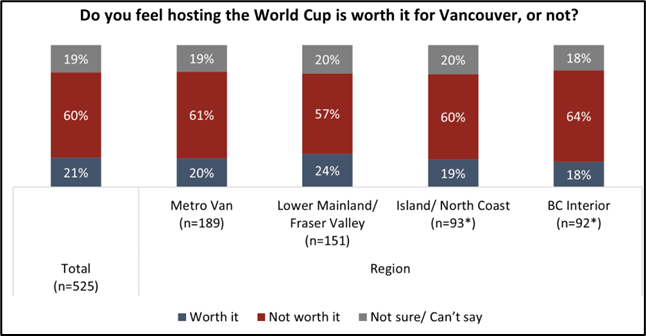

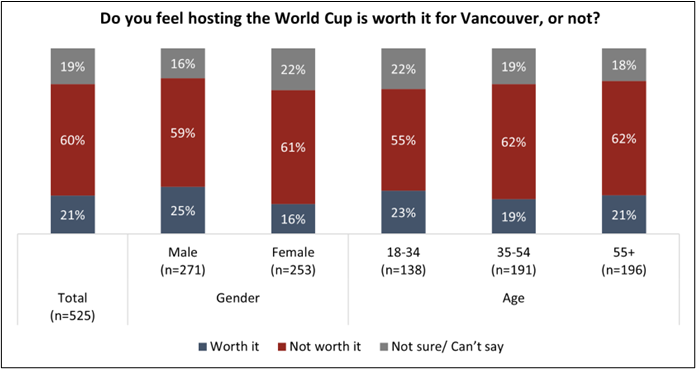

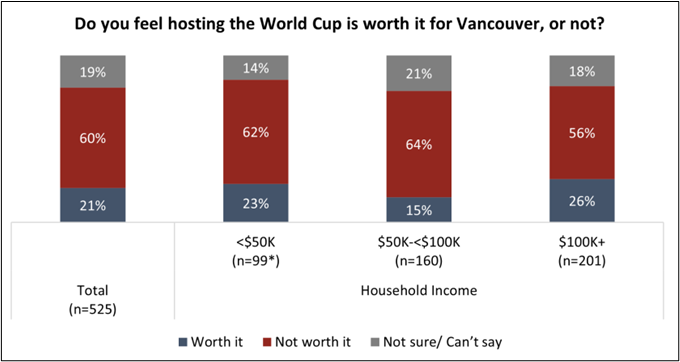

Since the Province of British Columbia and the City of Vancouver committed to hosting the FIFA World Cup, polls have repeatedly shown, by a 60 – 67% range citizens do not consider the cost nor the prestige “worth it.” This has likely escalated since the more realistic costs of hosting have been revealed, and the governments have not seen fit to release the Vancouver contract nor their internal memorandum outlining their decision-making processes. The following surveys show that the province as a whole and by age and income are not fans of what is essentially imposed on them – even though most polls indicate an interest in watching the games. (Source: Angus Reid Institute, “World Cup Red Card?”, July 5, 2024.)

By Province of British Columbia Regions (Note: Games played in Metro Vancouver)

By Age and Gender

By Household Income

(Source: Angus Reid Institute, “World Cup Red Card?” July 5, 2024)

If Vancouver hosts its maximum number of games, seven, and with costs sure to grow, it is very likely that it will cost $100 million per game to stage – a ridiculous amount for a City and Province in big debt, and where its infrastructure, including parks and recreation facilities, are in big decay. For a family that cannot find ice time for hockey; or whose local soccer fields are in disrepair or too few and far apart; or whose community centres and swimming pools are closed to lack of care; paying the FIFA ransom is too much. In 2018 the then British Columbia government said no to FIFA, refusing they said to sign a “blank cheque.” A few years later the same government issued this cheque.

The question remains why did two Canadian cities enter into the FIFA orbit, and at such a high cost and low benefit to the actual taxpayers and citizens? This was hardly a priority for those living here and certainly not at the costs projected and which will inevitably be greater yet. The era of governments being attracted to shiny object mega events, at the public’s expense, has been fading for some time. Vancouver seemingly did not get this memo. Therefore, we can hope for an enjoyable 2026 World Cup, with perhaps the Canadian National Team doing well, and then a hard and fact and data driven analysis of this event and its actual cost and benefits revealed and measured against other necessities and opportunities. This would be a real World Cup legacy.