Smart Growth refers to urban design and transportation planning agendas which its adherents believe create vibrant, high density urban centers with an ever decreasing dependency on the automobile. Smart Growth is promoted as a panacea for an increasingly wide range of urban and social challenges, with its agenda now permeating many of the planning departments in cities and regional districts throughout North America. Today many bureaucrats and politicians are beholden to

this agenda.

“Although smart-growth advocates like to portray themselves as underdogs, Smart Growth has not only been the dominant vision in federal legislation since 1991, it or some variation dominates transportation planning in many states and urban areas, particularly on the Pacific Coast and in some cases has been the dominant paradigm since the 1970s.”1

The contrarian view to Smart Growth is that it is little more than a cleverly marketed rehash and acceleration of control and containment urban planning strategies, with influence and power exercised by ideologically driven city planners and self-serving politicians, and their supporters.

The role of Smart Growth is central to any debate on what constitutes prudent and practical urban planning and the quality of life of its residents. The control purpose of this brief article is to try to quantify if actual Smart Growth civic results support its very premise and multitudes of promises, or not. The analysis presented herein is that Smart Growth expands and extends the politicization of a city’s real estate markets and in turn severely distorts a city’s actual livability and affordability. Smart Growth has not lived up to its rhetoric or promises.

But Smart Growth proponents and promoters have a vested interest, both ideological and financial, in seeing their brand grow. Therefore, after the passing global housing crisis of 2007-2008 when its supporters were on the defensive, they are aggressively promoting their agenda including publishing several books praising the city and Smart Growth, most of which are anecdotal and rhetorical with little statistical data, and all are dismissive of the suburbs and the social mobility they afford citizens. “To see that cities are resurgent centers of wealth and culture, all you need to do is set foot in one, or simply set foot in a bookstore,”2 proclaims Leigh Gallagher in her book The End of the Suburbs. Other recent titles include Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class and Whose Your City?, Bruce Katz and Jennifer Bradley’s The Metropolitan Revolution, Alan Ehrenhalt’s The Great Inversion and the Future of the American City, Jeff Speck’s Walkable City, Charles Montgomery’s Happy City and Edward Glaeser’s “love letter to cities,”3 Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier and Happier.

These books promote the wisdom of Smart Growth, while demonizing the suburbs, using the term urban sprawl as a prerogative. From its inception, the Smart Growth movement has been convinced of its intellectual superiority, stating that the choice is about either “the idiocy of suburban sprawl or the superiority of Smart Growth.”4 In order to create traction and entrench this agenda, a series of alliances have been formed under the Smart Growth umbrella, such as the anti-automobile group and those focused on environmental issues. “Sustainable” and “Green” have become watchwords for urban designers, who tend to use the terms rather interchangeably to express their concerns about the effects of development on the local and global environment.5 While Smart Growth proponents may argue that their movement is hegemonious, it more accurately resembles a coalition, or alliance, of self-interests. “Although many opponents of sprawl believe their beliefs are based upon a rational and disinterested diagnosis of urban problems, their actions often involve powerful, even if usually unacknowledged, self-interest.”6 Smart Growth in actual practice is politicization of urban real estate. Therefore, how smart has Smart Growth in practice actually been and who has benefited from it? To answer these primary questions, we need to consider and address the following:

- By its own definition and agenda, what is Smart Growth?

- Is Smart Growth a movement or a theory, or in actual practice a coalition or an alliance of convenience of groups and elites who support and use one another to achieve their own specific objectives? This paper will propose that while Smart Growth was initiated as a theoretical movement, in practice it is a politically expedient alliance of self-interests.

- What are the Smart Growth city meccas and what lessons can we learn from examining them? This paper briefly analyzes what has occurred in three of the most often cited Smart Growth successes in the world: Portland, Oregon, Vancouver, British Columbia and Copenhagen, Denmark.

- What have been the actual measurable results and consequences of Smart Growth on cities? Are citizens actually better off in Smart Growth cities or the suburbs? This is central to the future debate. In his balanced analysis, Sprawl: A Compact History, Robert Bruegmann proposes that perhaps the professed Smart Growth solution promoted by a few is far worse than any perceived problem associated with the suburbs or sprawl, stating, “our highly-dispersed urban regions deserve some respectful attention before we jump to the conclusion that they are terrible places that need to be totally transformed.”7

Regardless of how commendable the idealism of its proponents might have been, Smart Growth has created its own set of problems in practice, especially with regards to housing affordability. That its proponents have not adjusted their position to reflect realities has revealed that the self-interests of the various members of the Smart Growth alliance trump this proposed idealism.

What is Smart Growth?

Smart Growth traces its origins to an assortment of new urbanism movements which believe central planning by supposed experts will create civic oases within any city, regardless of its size, location, history and diversity. The genesis of the current Smart Growth movement took place in 1991 at a conference at Yosemite Park’s Ahwahnee Hotel where two groups, one led by the husband and wife architect team of Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and the other by transit planner Peter Calthorpe, met with their counterparts to discuss how to reconcile their differences of opinions and objectives while focusing on their shared belief in a more ideological and centralized approach to planning and urban design. (The Duany group was focused more on community development, while the Calthorpe side stressed transportation as the way to structure and restrict or encourage urban development.) From this conference a set of design principles known as the Ahwahnee Principles were adopted to address the group’s belief that, “existing patterns of urban and suburban development seriously impair our quality of life.”8

The anecdote proposed was Smart Growth, a term first promoted by Maryland Governor Parris Glendening in 1996, whose office used it, “because it was ‘hard to oppose’: anyone who questioned Smart Growth could be (and usually was) immediately accused of favoring “dumb growth.”9 From its inception, Smart Growth and its leaders have self-promoted themselves as intellectually and morally superior to their counterparts as highlighted by their own words. “What has emerged from these primordial rumblings is a sort of unified field theory … a half-century of, yes, dumb growth has put our nation and our species in a truly precarious position. The movement against suburban sprawl, which began principally as an aesthetic and social critique, is now working in the service of science.”10 Smart Growth has subsequently become a slogan affixed to an urban and political control agenda. The following six goals are the verbatim extracts from the Smart Growth playbook:11

- Neighborhood Livability. The central goal of any Smart Growth plan is the quality of the neighborhoods where we live. They should be safe, convenient, attractive and affordable for all people. Sprawl development too often forces trade-offs between these goals.

- Better Access, Less Traffic. One of the major downfalls of sprawl is traffic. By putting jobs, homes and other destinations far apart and requiring a car for every trip, Sprawl makes everyday tasks a chore. Smart Growth’s emphasis on mixing land uses, clustering development, and providing multiple transportation choices helps us manage congestion, pollute less, and save energy.

- Thriving Cities, Suburbs and Towns. Smart Growth puts the needs of existing communities first. By guiding development to already built-up areas, money for investments in transportation, schools, libraries, and other public services can go to the communities where people live today.

- Shared Benefits. Sprawl leaves too many people behind. Divisions by income and race have allowed some areas to prosper while others languish. As basic needs such as jobs, education and health care become less plentiful in some communities, residents have diminished opportunities to participate in their regional economy. Smart Growth enables all residents to be beneficiaries of prosperity.

- Lower Costs, Lower Taxes. Sprawl costs money. Opening up green space to new development means that the cost of new schools, roads, sewer lines and water supplies will be borne by residents throughout metro areas. Sprawl also means families have to own more cars and drive them further. And where convenient transportation choices enable families to rely less on driving, there’s more money left over for other things, like buying a home or saving for college.

- Keeping Open Space Open. By focusing development in already built-up areas, Smart Growth preserves rapidly vanishing natural treasures. From forests and farms to wetlands and wildlife, Smart Growth lets us pass on to our children the landscapes we love. Communities are demanding more parks that are conveniently located and bring recreation within reach of more people. Also, protecting natural resources will provide healthier air and clearer drinking water.12

To achieve these lofty goals, Smart Growth America outlined a ten step guide to implement and achieve Smart Growth. This checklist’s words are purposely generic, with no means proposed to measure actual results and benefits. To Smart Growth consultants, their mantra is simply to show “the idiocy of suburban sprawl … and the superiority of Smart Growth.”13

- Mix Land Uses. New, clustered development works best if it includes a mix of stores, jobs and homes. Single-use districts make life less convenient and require more driving.

- Take Advantage of Existing Community Assets. From local parks to neighborhood schools to transit systems, public investments should focus on getting the most out of what we’ve already built.

- Create a Range of Housing Opportunities and Choices. Not everyone wants the same thing. Communities should offer a range of options: houses, condominiums, affordable homes for low income families and “granny flats” for empty nesters.

- Foster “Walkable,” Close-Knit Neighborhoods. A compact, walkable neighborhood contributes to people’s sense of community because neighbors get to know each other, and not just each other’s cars.

- Promote Distinctive, Attractive Communities with a Strong Sense of Place, Including the Rehabilitation and Use of Historic Buildings. In every community, there are things that make each place special, from train stations to local businesses. These should be protected and celebrated.

- Preserve Open Space, Farmland, Natural Beauty, and Critical Environmental Areas. People want to stay connected to nature and are willing to take action to protect farms, waterways, ecosystems and wildlife.

- Strengthen and Encourage Growth in Existing Communities. Before we plow up more forests and farms, we should look for opportunities to grow in already built-up areas.

- Provide a Variety of Transportation Choices. People can’t get out of their cars unless we provide them with another way to get where they’re going. More communities need safe and reliable public transportation, sidewalks and bike paths.

- Make Development Decisions Predictable, Fair and Cost-Effective. Builders wishing to implement Smart Growth should face no more obstacles than those contributing to sprawl. In fact, communities may choose to provide incentives for smarter development.

- Encourage Citizen and Stakeholder Participation in Development Decisions. Plans developed without strong citizen involvement don’t have staying power. When people feel left out of important decisions, they won’t be there to help out when tough choices have to be made.

But is one set of guidelines even remotely practical for all cities to follow? There are currently 4,000 cities on the planet today with a population of 100,000 or more.14 Each of these cities is unique, the result of its geography, history, culture and people. Those opposed to Smart Growth believe that due to the uniqueness of each city and indeed each country and continent, a one size fits all approach to urbanism is impractical and impossible to enact. “The presumption that American and European prescriptions for cities are transferable often leads to quite absurd results.”15 Conversely, the Smart Growth movement believes that central planning can indeed work regardless of the locale. “On the contrary, the language of U.S. sprawl and its containment is now readily borrowed and applied in studies and policy prescriptions for cities in developing countries as if it were self-evident that sprawl is, indeed, a universal phenomenon requiring a universal response.”16

In order to promote and implement such an ambitious agenda, its proponents require control over planning processes at the civic and regional levels of governments, while leveraging the political clout of heavily populated cities (and their vote) to secure government funding for its heavily tax subsidized agenda. In order to secure this support, and then exercise this new power, the Smart Growth movement morphed into an alliance of convenience between groups with some shared interests, but with their own ideological and financial agendas required. From the start, two cities, Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, British Columbia (the author’s home region) were heralded as paragons of Smart Growth virtues. These two cities show Smart Growth has not evolved as envisioned. In the case of Vancouver its housing affordability crisis has severely altered its former poster city status.

Portland

Portland, Oregon is the most referenced Smart Growth city. Its success or failure is critical to this subject. “Why is this debate so acrimonious and how can the basic facts in the case be so much in doubt? Perhaps the most plausible answer is that because Portland has become the prime symbol of the anti-sprawl campaign, the question of whether the ‘Portland system’ works or doesn’t work has enormous ideological significance.”17 Portland’s prevalence in the Smart Growth movement has perhaps more to do with its culture and politics, as, “economically the city did so poorly in comparison with other American cities and many of its West Coast neighbors during much of the mid-twentieth century … it has remained a small city with neither the pollution that heavy industry would have generated nor a large and poor minority population.”18 Portland, therefore, was not necessarily the best template to build the Smart Growth agenda on.

Portland’s much touted successes in urbanism have been scrutinized extensively, especially by former Portland resident and persistent Smart Growth critic Randal O’Toole. For several years O’Toole has systematically examined the land use and transportation policies of the Portland Metropolitan region. In 2007 he wrote an analysis entitled “Debunking Portland: The City that Doesn’t Work.”19 While Portland has won numerous awards from the American Planning Association and other similar groups, and is always cited as the primary North American example of progressive urbanism and Smart Growth, O’Toole counters much of the hype by contrasting the rhetoric with actual results, stating that Smart Growth has limited housing options and choice, increased taxes and simply has “not produced the utopia planners promised.”20

The Smart Growth movement invested very early much of its ideological capital in Portland, a city whose politicians and planners embraced the chance to not only brand their city, but themselves. Well before real scrutiny on what Smart Growth actually delivered began, the Portland model had been implemented in cities throughout North America. This prevalence has been questioned by academics such as Robert Bruegmann who questions this reference.

“After more than twenty-five years in operation, the results of the Oregon (Portland) experiment are controversial and puzzling. Growth control in Portland, like the text of the Bible, seems to provide almost anyone studying it evidence to bolster a preexisting viewpoint. According to proponents and many of the journalists writing for the national press, the Portland area growth management system has accomplished most of its goals. These individuals say that the Portland region today remains a highly livable, green metropolis that has managed to control its own destiny by careful planning … Other observers range from skeptical of specific claims to adamant that the system as a whole has been a failure, and a fraud to boot.”21

Like Portland, Vancouver was often touted as a Smart Growth mecca. Both cities’ progressive politicians and planners shared visions and policies. (Vancouver’s new Director of Planning previously held this title in Portland.) But Vancouver is now a prime example of the unintended (but not unexpected) consequences of Smart Growth.

Vancouver

Vancouver, British Columbia, is one of the most stunningly beautiful cities in the world. Few (including this author) can imagine living anywhere else. Its natural setting, with the North Shore mountains framing the region’s peninsula which juts out into the Pacific Ocean’s Burrard Inlet captivates visitors. The unquestionable crown jewel of the city is Stanley Park, the 1,000 acre tip of the peninsula which lies beside the city core and has been wisely left unspoiled since the city’s founding in 1886. Therefore, Vancouver owes — and will always owe — its image to nature, not any planning agenda. Whenever Vancouver places at or near the top of most beautiful or livable cities in the world, it is the city’s natural beauty that earns the most praise and points, and which offsets deductions for the cost of housing and living in the region. Vancouver is not a large city. With a population of 603,502 it currently sits as the 580th largest city by population in the world.22 Vancouver is also evolving into becoming two cities. Its heavily congested downtown core, formerly the center of its business community, has been transformed by high-rise residential condominiums replacing office towers.

It is this downtown core which has been the focus of Vancouver’s Smart growth experiment.

Vancouver currently sits atop the Metro Vancouver Regional District, which is comprised of 21 neighboring municipalities, whose combined population is 2,313,000.23 Because Vancouver was able to effectively control and/or influence the Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) (now known as Metro Vancouver), much of the entire region’s policies have been reflective of a general Smart Growth agenda, which focuses on the broad themes of livability and sustainability and the promotion of Vancouver itself. The region’s 1996 strategy paper entitled “Livable Regions Strategic Plan,”24 has formed the basis of all central planning in the region to date. This strategic plan, like similar Smart growth documents copied throughout North America offer a wide focus while being non-specific with regards to benchmarks, setting metrics and cost benefit analysis. The new current strategic plan attempts to map out land use policy to 2040 (a date used with remarkable consistency within the Smart Growth movement). This plan does not identify short comings of previous plans, nor address previous assumptions which proved false. Nowhere does the plan rationally address how you can achieve livability without affordable housing for actual residents. “District planners narrowly focused on two goals: avoiding urban sprawl and minimizing automobile driving.”25 They have deliberately ignored warnings about instituting a control agenda.

Back in 1973, three years before Vancouver’s first regional district plan was implemented, the region hired internationally known planner Hans Blumenfeld to review its proposed strategies. Blumenfeld had helped prepare Toronto’s regional plan and was the author of the 1967 book, The Modern Metropolis: Its Origins, Growth, Characteristics and Planning. Expecting to be complimented on the region’s vision, these planners and politicians were instead warned that their focus and efforts would little reduce automobile driving and that containment and green and agricultural zones, no matter how well intentioned, would impose high costs and housing affordability issues for future residents, who he argued strenuously were not yet part of the region and would eventually pay the costs associated with policies so far reaching. Blumenfeld warned that planners should not presume to know either the preferences or future needs of a region’s residents better than those residents themselves. He noted that, “in 15-20 years, 80 percent of the population of the GVRD will consist of persons who are not here yet. They have no vote but it is their living conditions which are determined now.”26 Perhaps it was Blumenfeld’s memos stating that the individual mayors and councilors, who made up the GVRD Board, were in an inherent conflict of interest about the future growth of the region that stymied his perceptive warnings.

It is no secret that concerns about urban sprawl were partly motivated by fiscal considerations, forced on the municipalities by their almost complete dependence on the real property tax. People who own homes outside of the city do not pay taxes to the city. By restricting rural development, the officials who approved the regional plan were enhancing the revenue base for their cities.27

To drive home the point, and based upon his global experiences, Blumenfeld warned that since expensive homes pay higher property taxes than less expensive ones, cities had a financial incentive to approve expensive housing, including high-rise condominiums, and actually discourage affordable housing. The results, he argued, were quite predictable. Greater Vancouver would incur, “oligopolistic high land prices, which are usually blamed on speculator and large scale developers, but in fact are created by municipal policies.”28 This is exactly what has occurred in the City of Vancouver and has spread throughout the region. In addition to its now horrendous real estate matrix and affordability, Vancouver’s transportation system is a mess, and the overall infrastructure of the region undersized for its growth. The goals of livability and sustainability that the region’s planners subjectively promised have not been realized, and it can be argued have effectively been compromised due to unaffordable living costs and resulting in an economy now based largely upon real estate speculation, much of it foreign influenced. This may surprise those in the planning and real estate and development communities.

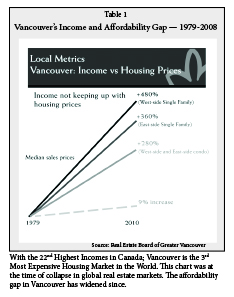

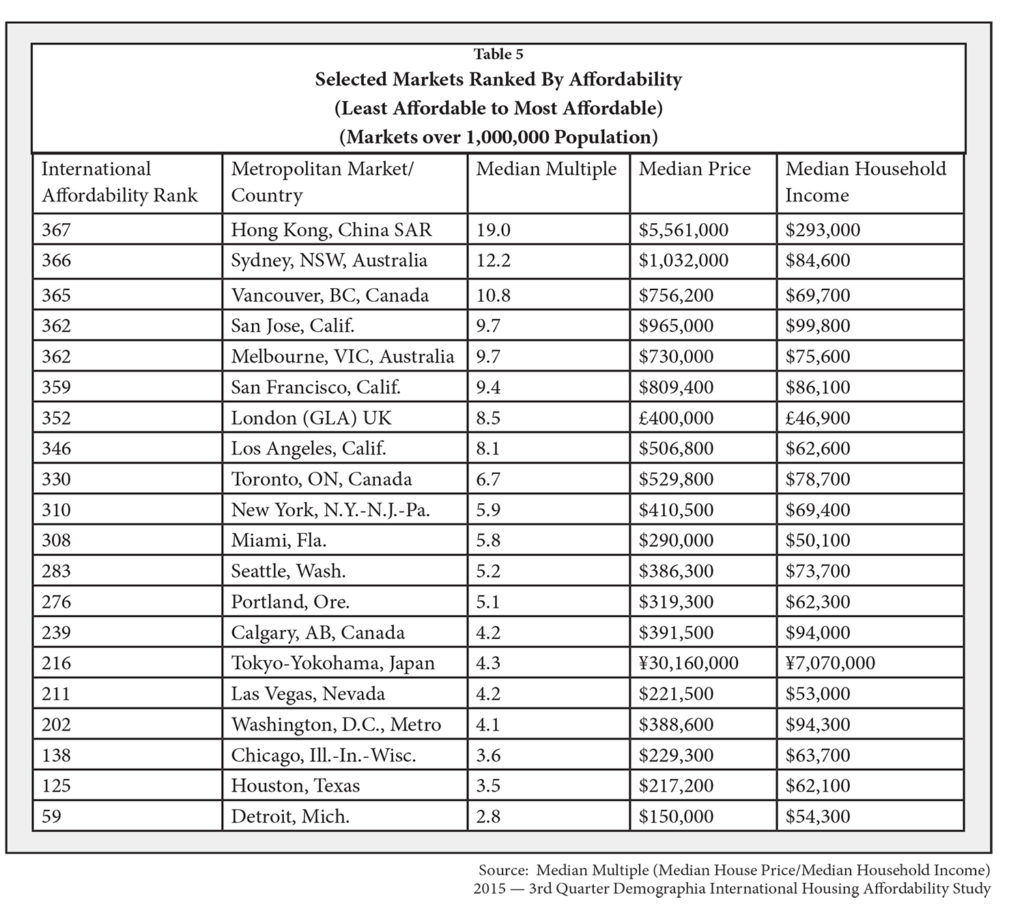

When a city loses control of its housing market, it eventually loses control of much of its economy. Vancouver’s housing is now the second least affordable in the world, and with that gap, wages and housing costs widens each year. The following table, produced by the City of Vancouver itself, shows that for the past thirty years, a period simultaneous to the implementation of Greater Vancouver’s Livable Region Smart growth plan, median incomes moved up only 9 percent in three decades, while the steep trajectory of its housing prices paralleled the launch of the region’s Smart Growth zoning containment strategy. The gap has widened considerably in recent years.

When a city loses control of its housing market, it eventually loses control of much of its economy. Vancouver’s housing is now the second least affordable in the world, and with that gap, wages and housing costs widens each year. The following table, produced by the City of Vancouver itself, shows that for the past thirty years, a period simultaneous to the implementation of Greater Vancouver’s Livable Region Smart growth plan, median incomes moved up only 9 percent in three decades, while the steep trajectory of its housing prices paralleled the launch of the region’s Smart Growth zoning containment strategy. The gap has widened considerably in recent years.

While the Livable Region, the Greater Vancouver Region central planning document focused on two goals, livability and sustainability, was light on actual numbers and benchmarks, planners and politicians had to realize early that their region’s housing matrix was volatile. The failure of planners and politicians alike to first acknowledge they had severely miscalculated the financial consequences of their Smart Growth agenda was only exceeded by their failure to retreat from these policies.

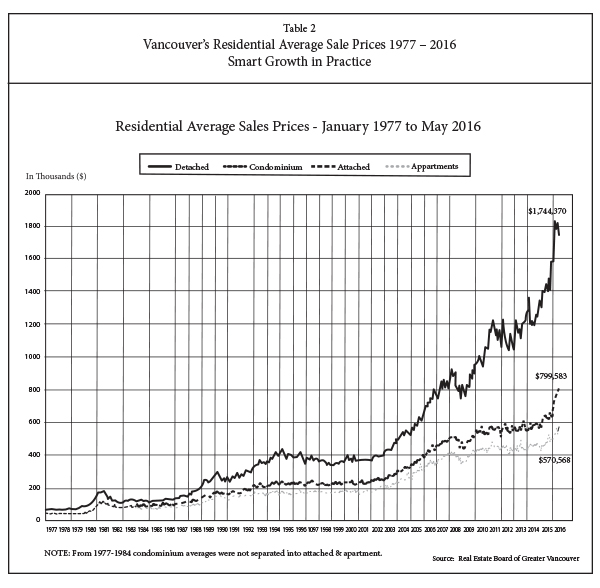

When you examine Vancouver’s housing data one has to ask, how could a city allow such a disparity to occur, perpetuate and even accelerate? These disparities have been accelerated when Vancouver alone in the world failed to place any restraints on foreign investment of its residential markets.29 As a direct consequence, Vancouver real estate has become a commodity. While much of the world believes Canada escaped the recent global real estate meltdown unscathed, that their banking system is sound, and that at worst a downward correction in housing prices will be at worst a “soft landing” (and not a bubble burst), this does not hold up to scrutiny. If you live in Vancouver, based upon its housing prices and wage structure, the housing affordability index indicates that depending on the housing type, fully 41.8 percent (condominium) to 87.8 percent (two story house)30 of pre-tax income is required to be able to qualify for the standard mortgage underwriting ratios. This explains why Canadians are now spending $1.65 — $1.70 for every dollar earned, higher spending than occurred in Europe and the United States when their housing bubbles burst.31

When you examine Vancouver’s housing data one has to ask, how could a city allow such a disparity to occur, perpetuate and even accelerate? These disparities have been accelerated when Vancouver alone in the world failed to place any restraints on foreign investment of its residential markets.29 As a direct consequence, Vancouver real estate has become a commodity. While much of the world believes Canada escaped the recent global real estate meltdown unscathed, that their banking system is sound, and that at worst a downward correction in housing prices will be at worst a “soft landing” (and not a bubble burst), this does not hold up to scrutiny. If you live in Vancouver, based upon its housing prices and wage structure, the housing affordability index indicates that depending on the housing type, fully 41.8 percent (condominium) to 87.8 percent (two story house)30 of pre-tax income is required to be able to qualify for the standard mortgage underwriting ratios. This explains why Canadians are now spending $1.65 — $1.70 for every dollar earned, higher spending than occurred in Europe and the United States when their housing bubbles burst.31

Residential real estate there is more a commodity and not about homes for people living and working in the city. This is completely contrary to what should motivate one to purchase residential real estate, according to Richard Florida. “Housing is different from other investments and for a very simple reason. The primary purpose of investing in a home is not to make money but to have a roof over one’s head.”32

And Vancouver’s median family incomes are well below the Canadian average of $76,040.33 Vancouver, the country’s third largest city and Pacific gateway, has a median family income (2011) of $68,970.34 Out of 28 Metropolitan cities surveyed by Statistics Canada, 21 had far higher median family incomes, with none being close to Vancouver’s housing prices. While Vancouver has long been the country’s most expensive housing market, with its natural beauty most cited as the reason, the city’s Smart Growth policies coupled with no restrictions on foreign purchases have rapidly accelerated this disparity and Vancouverites are paying more for less, with 500-700 square feet units, not the 900 square foot unit national average now common. The city’s owner occupied housing stock (2011) is 35 percent and rising — “the highest market share by far in Canada.”35 By comparison in the United States there are 4.4 million owner-occupied condominium units, which represent 5.8 percent of the country’s total owner-occupied housing supply, well below Canada’s overall total of 12.6 percent and Vancouver’s 35 percent.36 Rather than admit Smart Growth had harmed the region and reversed course, the region and, in particular, the City of Vancouver continued to build not for the local, but for the foreign market, most notably the mainland Chinese. Vancouver, where only 49 percent of the residents speak English, and 25 percent have Chinese as their first language “is no longer a domestic market — what occurs in China is now a greater effect on our housing markets, not the action of local residents.”37

Nowhere in any Smart Growth literature or projections is such an occurrence even contemplated. With control of their domestic housing market now largely out of the control, politicians and planners are now scrambling for solutions to Vancouver’s housing affordability crisis. While much of their plans are hybrids of the same Smart Growth policies that created the crisis, regional planners still try to be innovative, such as the move to laneway housing of which 1,000 building permits have been issued over the last five years in Vancouver. Unfortunately, these units, which replace the former garage in the alley, cannot be more than 750 square feet and must remain part of the main property’s title, are expensive. The average cost to complete a Vancouver laneway house, which incorporates about $85,000 in combined building fees and site costs, range from $250,000 to $350,000.38 Based upon current U.S. housing pricing averages, in selected American markets you could buy two detached homes for the price of one Vancouver laneway house.39

Vancouver’s planners and politicians thought they could control the Smart Growth genie, but instead are now trapped by its limitations. As a result, their plans to join the city’s green agenda and extensive social housing and community plans to its Smart Growth strategies has made the city extremely vulnerable on many levels.

Smart Growth: Rhetoric vs. Results

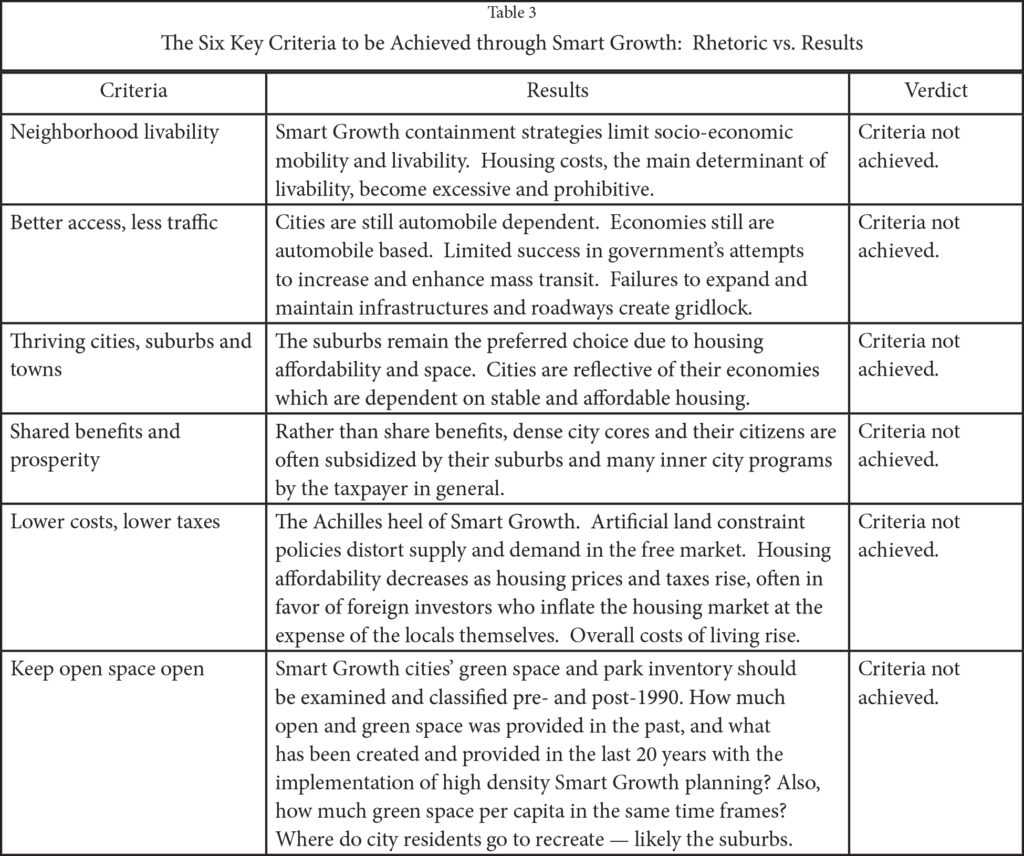

From its inception Smart Growth set a very high bar for itself, with its proponents proclaiming moral and intellectual superiority for their agenda, while always being dismissive of its opponents. Smart Growth promises and rhetoric have fallen well short of their stated objectives. Table 3 restates the six key goals and criteria which the proponents of Smart Growth use to promote their agenda. In actual practice, the goals do not live up with the results to date.

If Smart Growth has failed to meet its own targets, what lessons should be learned from this experiment in urbanism? The following seven conclusions and recommendations to date are offered so as to continue this debate on urbanism and to create cities which are actually livable and sustainable proceeds based upon facts and best practices.

1. Smart Growth is an oxymoron. It is about containment and political control and favoritism.

Smart Growth mislabels what has actually been practiced within cities that profess to exercise this agenda. As pointed out throughout this paper, Smart Growth is essentially about a few controlling the future of many. Through an ideologically driven containment strategy Smart Growth is an artificial use and application of restrictive zoning and development practices at the expense of the free market circumstances prevalent within industrial cities. By its nature and practice, Smart Growth puts groups into perpetual conflicts of interest. It is not smart, but cronyism in action. Smart Growth should be referred to and re-labelled as containment zoning. But are such policies and denigration of the suburbs really necessary? Are not the best functioning metropolitan cities a core-suburb combination? Characteristics we associate today with sprawl have actually been visible in most prosperous cities throughout history. Sprawl has been as evident in Europe as in America and can now be said to be the preferred settlement pattern everywhere in the world where there is a certain measure of affluence and where citizens have some choice in how they live.40

2. City and regional planning should be balanced. Strategic plans should be short term and target based.

Reporting and rating the well-being and strength of a city should not be anecdotal, rhetorical or self-serving. Civic pride is one thing. Presenting one city as a national or global standard for others to emulate is another. But this is what the Smart Growth movement has always done. They need champions to promote their agenda and this in turn has led to cities, such as Portland and Vancouver being offered as model cities to replicate. But this one size can fit all model of urbanism goes against common sense. Each city and its people are unique and reflective of the geography, climate, history, culture, demographics and economy of the city and metro region. Rather than impose ideology, urbanists should encourage best practices and basic analytics which can be used to improve quality of life and outcomes. Some of these analyses and benchmarks would include:

- Housing affordability;

- Housing options and the cost thereof;

- Infrastructure and transportation planning and funding;

- The financial and budget viability of the city including its long term pension and infrastructure liabilities;

- Property taxes and economic development and viability;

- Guidelines for green, park and school space per capita;

- The per capita costs and best practices basic and essential civic services such as waste removal, water, safety and security and the civic government itself; and

- There must be a clear division and transparency between the real estate and development industry and bureaucrats and politicians, to avoid conflicts of interest.

Developers and politicians use one another. This is self-evident when examining Smart Growth not in theory but in action. Smart Growth influences Official Community Plans and development bylaws favor density and control over the land supply — but their interpretation is always subjective and far too often political, with zoning approval density lifts tied to fee and amenity kickbacks to the city. Civic budgets are also increasingly dependent on development cost charges to fund their operating budgets, which together with always rising property taxes, reduce housing affordability and make the commercial real estate market cost prohibitive. What emerges are crony capitalism and a weakening of the market economy. Political connections and campaign funding should not be as important to a firm’s success as their track record and skillset.

3. It is the planners and politicians that must be constrained, not the free markets.

The more complex planners and politicians make city planning and governance, the more poor decisions and mistakes they will make. Smart Growth in practice diverts focus and attention, and financial resources, away from the basics — running a city. Instead, most Smart Growth cities are now locked into arbitrary 20-30 year strategic growth plans that they refused to repudiate. “Planners today rely heavily on the ‘visioning’ process in which planners or a few members of the public try to imagine what they would like their region to resemble in twenty years or more.”41

If politicians either buy into this Smart Growth visioning process, and/or do not challenge their staff to justify past and  proposed actions, then there are no effective checks and balances over their city’s evolution. Politicians become first complacent by their silence, and then often advocates who are willing to spend and commit city resources in support of actions and practices they perhaps did not fully understand or comprehend. In practice, how many civic politicians, or even their senior planners and bureaucrats, have the education, experience, expertise and other skills commiserate with making multi-million dollar strategic decisions? As virtually all do not, should not a slow and cautious approach green their actions, combined with a very healthy dose of skepticism when schemes are placed before them?

proposed actions, then there are no effective checks and balances over their city’s evolution. Politicians become first complacent by their silence, and then often advocates who are willing to spend and commit city resources in support of actions and practices they perhaps did not fully understand or comprehend. In practice, how many civic politicians, or even their senior planners and bureaucrats, have the education, experience, expertise and other skills commiserate with making multi-million dollar strategic decisions? As virtually all do not, should not a slow and cautious approach green their actions, combined with a very healthy dose of skepticism when schemes are placed before them?

4. Actual smart growth results and consequences must be quantified, measured, and debated.

The performance of real estate is relatively easy to both measure and quantify. Therefore, with regards to the promise, practice and actual outcomes of the Smart Growth agenda, a means and a method to assess its policies and grade them should be proforma. For example, Smart Growth studies and planning documents which have been embraced by many cities and regional governments always refer to the twin objectives of creating livability and sustainability, but how are these terms defined and a city’s adherence to them measured? To move away from either overly rhetorical attacks or defense of Smart Growth, its proponents should be able to address and measure objectively results to the following key questions and then debate the validity or not of the Smart Growth agenda.

- What defines livability and how can it be measured and quantified?

- What defines sustainability and how can it be measured and quantified?

- Housing price indexes that show a significant disparity between median household income and median housing prices in

- Smart Growth cities. Why? What is the correlation of this disparity between housing affordability and Smart Growth policies?

- How do property tax mill rates and assessments and taxation policies compare between those cities with Smart Growth land use policies and those without?

- What percent of property taxes and what percent of civic budgets are derived from commercial property classes and residential properties in Smart Growth cities? Is there a disparity between Smart Growth city taxation policies and those cities without such policies?

- What percent of a Smart Growth city’s annual budget derived from Development Cost Charge levies and other fees and payments are directly tied to the granting of development permits and density bonusing? How dependent have Smart Growth city budgets become on this revenue stream?

- Are city annual operating and capital costs in Smart Growth cities stable or not? What is their overall financial status — especially with regards to its infrastructure, long term debt and employee pension requirements?

- How objectively, consistently and fairly have Smart Growth cities applied their zoning bylaws, density bonusing, development design terms and projects? Does Smart Growth eliminate political interference and favoritism or increase it?

- Has Smart Growth policies and the cost of living associated with them actually increased the growth of the suburbs as people seek more socio-economic mobility, more affordable housing options and traditional detached homes and yards?

- What are the short and long term physiological and socio-economic impacts on individuals and communities increasingly residing in high rise condominium towers as opposed to traditional mixed-use communities and suburbs?

- Should green space/green use be quantified on a per capita basis? How can cities provide sufficient green space, green amenities and recreation facilities in dense downtown urban cores in sufficient quantity and quality for their population?

- Is it even possible to propose or promote a “happiness matrix” based upon urban design policies? Are cities a panacea to solve societal inequities and problems or a breeding ground for more of the same? How important is individual choice and socio-economic mobility of individual citizens to the well-being and growth and enhancement of cities?

- How exactly do dense urban core cities survive and function without their suburbs — especially as this urban-suburban tandem has been the norm for cities throughout history?

In essence, these and other questions are meant to actually assess and determine whether or not Smart Growth has proven to be a smart proposition for those cities which practice some form of it. Unquestionably, Smart Growth has raised housing costs, which in turn raise the overall cost of living. What can Smart Growth offer in exchange for such a direct impact on its citizens? That Smart Growth defenders continue to disparage the suburbs and other anecdotal and rhetorical soundings would seem to indicate that they cannot defend their brand objectively.

5. Housing Affordability: The Achilles’ heel of smart growth must be acknowledged and addressed.

5. Housing Affordability: The Achilles’ heel of smart growth must be acknowledged and addressed.

Early Smart Growth proclamations stated that its principles would provide a plethora of housing and neighborhood options, all situated in thriving communities that would be increasingly less auto dependent. While never overt in their claims about decreased housing costs, it was certainly implied that while “sprawl costs money,” Smart Growth did promise “lower costs, lower taxes,”42 and would “create a range of housing opportunities and choices.”43 This has clearly not occurred over the past generation. Empirical data shows that property taxes go in only one direction: up; that services once contained in the property tax bill (such as water and garbage removal) are off loaded directly to the owner and that housing prices, regardless of the unit type (detached; townhouse; condominium), and square footage, have increased.

Residents of Smart Growth cities pay directly and excessively as a result of these policies. And they may well be paying for less and less actual living space as housing prices rise.

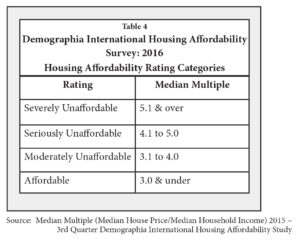

Before 1970, the median cost of housing throughout most of America was about two times median family incomes. Today, the  median homes still cost about two times median family incomes in states and urban areas that do not practice growth management. But areas with growth management have seen median prices soar to as much as 11 times median family incomes. This makes single-family housing unaffordable to all but the wealthiest people and fulfills smart-growth goals of increasing the percentage of people living in multifamily housing.44

median homes still cost about two times median family incomes in states and urban areas that do not practice growth management. But areas with growth management have seen median prices soar to as much as 11 times median family incomes. This makes single-family housing unaffordable to all but the wealthiest people and fulfills smart-growth goals of increasing the percentage of people living in multifamily housing.44

The Smart Growth alliance did not foresee, from the start, the obvious. When you artificially constrain housing markets and supply and demand metrics, housing prices are subject to wild variations and increases. This is what occurred almost from the start in Smart Growth cities — and which planners and politicians refused to acknowledge or correct. Rather than admit they had seriously miscalculated the key variable in city building and housing affordability, the Smart Growth alliance instead shifted their focus and promotion of the agenda more towards other areas such as green agendas and the anti-automobile — pro-bicycling movement. By design, the Smart Growth crowd avoids both housing unaffordability and ever limiting decreasing choice. “Smart Growth needs to address the spatial distribution of affordable housing. To date, few Smart Growth coalitions have incorporated affordable housing issues into their reform agendas.”45

6. The suburbs have not been, and will not, be the problem. Sprawl is not a pejorative.

For a comprehensive and balanced history of sprawl and its relationship with Smart Growth, University of Chicago professor Robert Bruegmann’s 2005 book, Sprawl, is an essential read. His work reveals that urban sprawl, or low density development around an urban fringe, is not a new phenomenon and dates back hundreds of years, perhaps to the very beginning of city building. Sprawl is a simple term but a complex phenomenon.46 Second, he makes a compelling argument that much of the opposition to sprawl comes from various elites and special interests that are largely focused on protecting their wealth and interest and status at the expense of lower classes. Finally, Bruegmann reviews actual results of Smart Growth agendas and challenges the reader to decide whether or not the remedies for sprawl did more harm or good, especially with regards to transportation congestion and housing costs. “Anti-sprawl alarmists have presented a picture that is at best a partial one. In some cases the diagnosis of problems caused by sprawl is based on tenuous evidence. In other cases it appears to be incomplete or even just wrong. In either case, such diagnoses rarely take into account the overwhelming evidence that sprawl has been beneficial for many people.”47

About “95 percent of the United States is rural open space.”48 This is obvious to anyone who has been in an airplane. It contradicts the key anti-suburb and sprawl argument of the Smart Growth crowd — that we are in effect running out of “space” and harming our environment. But suburbs have an enormous amount of green space, from backyards with their lawns and gardens, to parks, sports fields and other recreational space. Contrast that with hundreds of people living in smaller units stacked atop one another and with no personal green space, save perhaps a potted tiny balcony. The psychological and physiological advantages and disadvantages between owning and maintaining a detached home with a yard to keep up versus living in a condominium unit should form a major part of the Smart Growth debate. If the Smart Growth proponents can promote a “walkability dividend,” what about a “peace of mind” dividend achieved by having both house and yard space?

7. The automobile is not going away.

A city and region’s economy are, and will remain, vehicle dependent. Individual choice is also aligned with the automobile. The Smart Growth movement has not made the case, nor can they, that people will voluntarily give up their vehicles for bikes and mass transit. They have no solution to how an economy could be sustained without automobile and truck traffic. Therefore, planners should actually plan for a transportation system that remains auto dependent, and whose transit system reflects actual and verifiable ridership and flexibility. Both systems should also be consumption cost based, with neither subsidizing the other. By following a Smart Growth, anti-automobile agenda, many cities now face huge infrastructure and roadway deficits. Their budgets are focused on other expenditures and their tax and spending priorities are not sustainable. These decisions may well accelerate the growth of the suburbs, as citizens reject the high cost and limited choice of downtown housing options and the overall cost of living and taxation. This shift in growth and influence may actually leave some city cores orphans with diminishing power and influence — victims of their own hyperbole.

The automobile and vehicular traffic continue to be the preference of free citizens. Their necessity and importance on economies will remain for generations to come. Despite efforts to demonize automobiles and roadways, Smart Growth has neither diminished people’s dependence on or preference for the automobile, nor significantly increased heavily subsidized mass transit ridership.

Conclusions

The Smart Growth movement ascended quickly. Within a generation, in tandem with the global warming and anti-automobile proponents, these groups and their leaders who believed that they could both micro and macro plan cities and regions to their visions, came to dominate much of the civic planning community. So assured were they of their wisdom, they named their movement Smart Growth, and by extension labelled opponents as practitioners of dumb growth. Along the way they have also tried to diminish the concept of the American dream, the house and yard in the suburbs, or whatever choice of housing one aspires to and is prepared to work for. As such dreams and individual choice are contrary to what Smart Growth tries to impose, the bogeyman of Smart Growth — suburban sprawl — was raised. Therefore, from the start, Smart Growth both claimed its proponents and its ideas were superior to others, and that they, not you/us, should make life defining and altering decisions for others. If something is actually Smart and good for you and yours, would you not gladly embrace it on its own merits? How has such a rapid and fundamental shift in thinking occurred in such a short period of time?

First, the Smart Growth movement and their allies are career and ideologically driven. They have been persistent. Second, they have had to win over a relatively small, and prone to group think cadre — professional planners and politicians. Smart Growth is about power and control — which appeals to these bodies. Third, natural skeptics and opponents to such schemes, the real estate and development industries, banks and business community and the media, have failed to adequately challenge or hold accountable those promoting the Smart Growth agenda. Several have become temporary beneficiaries of the agenda itself. Many in the development and real estate communities have been especially culpable. In exchange for perceived short term benefits, such as a successful rezoning application and additional building density (event though they have paid directly and indirectly for much of this), these groups who are best able to analyze the trend lines of unsustainable and unaffordable housing metrics and prices continue to work behind closed doors with city planners and politicians for short term results. To be successful in real estate requires a steady supply of consumers, in this case purchasers of residential units and commercial tenants. When a city or region loses control over its real estate market supplies, they have lost their ability to control their economic destiny. Eventually housing and real estate corrects itself, and with it, purges those firms which did not practice fundamentals, and relied instead on cronyism.

Fourth, the public is increasingly disengaged from the political process, especially the millenials who Smart Growth advocates say they are planning for and who will face the hardest cost and consequences of its containment policies. Local government, once thought to be the quiet and least intrusive form of government, is in fact the most intrusive of the three levels.

The main focus of this article is to encourage objective analysis and debate on the merits and limitations of the various planning and political agendas currently under the Smart Growth umbrella. Smart growth proponents have now had a full quarter century to prove their claims and back these up with objective data — not their ongoing and self-serving recitation of anecdotal comments. Cities were once considered the least obtrusive and most quietly efficient level of government. Their function and responsibilities were straightforward and easily understood. Civic politicians were often hands-on and respected, moderating their power prudently, including their ability to classify, zone and tax land. But once ideologically driven planners and politicians and the coalition and alliances formed around Smart Growth emerged, cities have changed, and their futures uncertain. Cities around the world are in transition.

The Suburbs and City Cores have Peacefully Co-Existed Forever

Sprawl is perhaps the best single edition on the history of the suburbs and city cores. The book effectively argues that Smart Growth has an element of elitism to it, and that individuals themselves should determine where and how they live. The book highlights that “sprawl” is not a recent phenomenon and should not be vilified in support of Smart Growth. If Sprawl — or better defined suburbia — has always been present in one form or another throughout history, then there really is no need for a “Smart Growth anecdote” for a condition, suburbia, which has always been naturally occurring.

This article has argued that when assessed strictly against its own lofty words and promises, Smart Growth has failed. In actual practice, Smart Growth denotes the overt politicization of local real estate markets and resulting conflicts of interests. By demonizing suburbia, even though the suburbs have been a natural extension of cities since recorded time and remain the living preference of most citizens, Smart Growth depends more on rhetoric than facts. By proclaiming their actions as “smart,” and contrary opinions as irrelevant, Smart Growth proponents too aggressively pushed and imposed their agenda on planners and politicians without due consideration of the unintended consequences of Smart Growth in practice, especially housing unaffordability. Simply stated, Smart Growth over promised, and under-performed — big time. Smart Growth literally and figuratively has morphed into dense growth.

Endnotes

1. O’Toole, Randal, Gridlock, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., 2009, page 40.↩

2. Gallagher, Leigh, The End of the Suburbs, Penguin Books, New York, 2013, pages 166-167.↩

3. Ibid.↩

4. Duany, Andres, Lydon, Mike and Speck, Jeff, The Smart Growth Manual, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2010, page xvii.↩

5. Zyscovich, Bernard, Getting Real About Urbanism: Contextual Design for Cities, ULI – The Urban Land Institute, Washington, D.C., 2008, page 52.↩

6. Bruegmann, Robert, Sprawl: A Compact History, University of Chicago, Chicago, 2006, page 161.↩

7. Ibid., page 12-13.↩

8. O’Toole, Randal, The Vanishing Automobile and Other Myths: How Smart Growth Will Harm American Cities, Thoreau Institute, Bandon, Oregon, 2001, page 138.↩

9. O’Toole, Randal, The Best-Laid Plans, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., 2007, page 93.↩

10. Duany, Andres, Lydon, Mike and Speck, Jeff, The Smart Growth Manual, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2010, page xii.↩

11. Duany, Andres, Lydon, Mike and Speck, Jeff, The Smart Growth Manual, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2010, Appendix.↩

12. Ibid., page xvii.↩

13. Ibid.↩

14. Angel, Shlomo, Planet of Cities, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2012, page 3.↩

15. Ibid., pages 13-14.↩

16. Ibid., page 144.↩

17. Bruegmann, Robert, Sprawl: A Compact History, University of Chicago, Chicago, 2006, page 207.↩

18. Ibid.↩

19. O’Toole, Randal, Policy Analysis, July 9, 2007.↩

20. O’Toole, Randal, “Debunking Portland: The City that Doesn’t Work,” CATO Institute, Policy Analysis, January 9, 2007, page 1.↩

21. Bruegmann, Robert, Sprawl: A Compact History, University of Chicago, Chicago, 2006, page 207.↩

22. City of Vancouver, 2011 Population Census.↩

23. Statistics Canada, 2011 Metro Vancouver Population Census.↩

24. Greater Vancouver Regional District, “Livable Strategic Plan,” 1996.↩

25. O’Toole, Randal, Unlivable Strategies: The Greater Vancouver Regional District and the Livable Region Strategic Plan, The Fraser Institute, Vancouver, 2007., page 3.↩

26. Ibid., page 12.↩

27. Ibid.↩

28. Ibid.↩

29. McCarthy, William, “Seller Beware: The Impact and Consequences to Date of Asian Investment in Metro Vancouver’s Real Estate Market,” The Counselors of Real Estate, Real Estate Issues, Chicago, 2011.

McCarthy has also written a longer version of this article, focusing on the blatant politicization of Vancouver’s real estate markets and its corresponding Smart Growth agenda. This thesis was part of his Master of Arts in Integrated Studies program at Athabasca University.↩

30. Royal Bank of Canada Economics and Research, “Housing Trends and Affordability” February 2013.↩

31. National Post, “Really There is a Recession Right Now,” April 15, 2013.↩

32. Florida, Richard, Whose Your City, page 139.↩

33. Statistics Canada, Median Table Income, 2013.↩

34. Ibid.↩

35. Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Canadian Housing Observer, 2013, page 2-1.↩

36. Ibid., page 2-9.↩

37. Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver, “Future Trends in Real Estate,” December 3, 2013.↩

38. For Vancouver, B.C. laneway house prices and bylaw information see www.lanefab.com ↩

39. To view American housing prices see http://us.spindices.com↩

40. Bruegmann, Robert, Sprawl: A Compact History, University of Chicago Chicago, 2006, page 17.↩

41. The Fraser Institute, Public Policy Source, “Unlivable Strategies,” page 25.↩

42. Duany, Andres, Lydon, Mike and Speck, Jeff, The Smart Growth Manual, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2010.↩

43. Ibid.↩

44. O’Toole, Randal, Gridlock, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., 2009, page 55.↩

45. “Smart Growth: The Future of the American Metropolis?” page 21.↩

46. Bruegmann, Robert, Sprawl: A Compact History, University of Chicago, Chicago, 2006., page 164.↩

47. Ibid., page 13.↩

48. O’Toole, Randal, The Best-Laid Plans, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C., 2007, pages 97-98.↩