Reprinted from Real Estate Law Journal Volume 52 Issue 4, with permission from Thomson Reuters. Copyright © 2024. Further use without permission of Thomson Reuters is prohibited. For further information about this publication, please visit https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/products/law-books, or call 800.328.9352.

ABSTRACT

LOOMING DEBT DEFAULTS: LOAN DUE DATES – Business and Societal Implications

Since the start of 2024, there has been a flurry of defaults on office loans.

These defaults have and are taking place for many reasons. The need to refinance loans that have become due or are coming due in this time frame of the end of 2023 and in to 2024 has been an important subject of discussion in financial circles. The need to refinance loans is not a new event. What is of recent, current development is the lack of lenders who are willing and able to refinance the loans in question at rates and on terms that are even close to those terms that existed when the loans were originated, such as 5 years ago.

If, for example, a loan was placed on office property 5 years prior to this refinancing position in 2024, such loan terms commonly provided for a loan to value ratio of about 65% or 70%. That is, if a building had a valuation of 100 million, the loan would have normally been around 65 to 70 million. Assume the outstanding balance on the loan, today, is still close to 65 million. Today, the lender who is willing to consider refinancing the loan may only allow a 60% loan to value ratio, i.e., a loan of 60 million, assuming the value of 100 million. Thus, the borrower would need to add additional equity to obtain the refinanced loan to pay off a loan of 65 or 70 million.

In summary:

But the above ratio is not the greatest concern for the borrower, if the market value of the building in question is now only 70 million. That is, in 2024 many office buildings that might have been valued much higher a few years ago, such as the example with the 100 million valuation that was determined 5 years ago, may now, in 2024, be valued at only 70 million. This means a lender might only be willing to provide a loan on the current 2024 building valuation, and possibly even with a ratio of only 60% of the valuation of the building. This means in the example presented, the loan would be 60% of 70 million, or a loan of only 42 million.

The combination of only the two variables noted above, the loan to value ratio and the drop in valuation of the building, resulted in a borrower who must provide much more equity to be able to obtain the refinancing.

This example did not consider other potential problems for the borrower, such as an increase in interest rates, a drop in net operating income because of lower rental rates, etc.

The combination of the above financial factors adversely impacts the borrower. In turn, such problems encourage borrowers, a fortiori, to pressure appraisers for higher valuation conclusions that would help the borrower obtain financing.

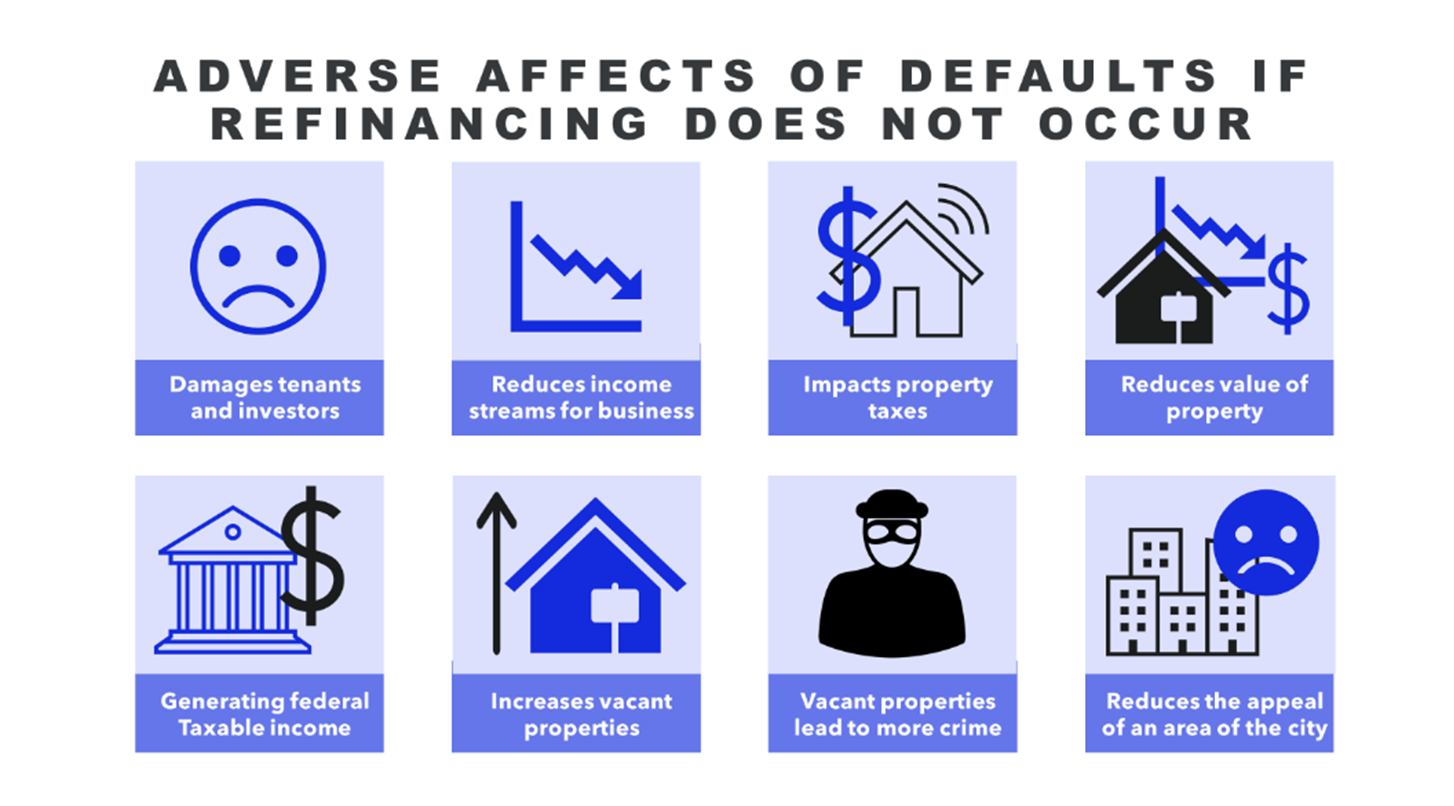

The defaults that occur if the refinancing does not take place damages investors and tenants in the building, reduces the income stream for many businesses that depend on traffic from the building in question that needs the refinancing, impacts property taxes and other government revenue, and often reduces the quality of property in each area, such as the core, downtown area. As discussed in this Note, defaults on loans have additional, adverse implications in many cases, such as generating federal taxable income to a defaulting borrower, creating more crime in areas where there is a greater amount of vacant property, and otherwise reducing the appeal of a given area of a city, such as the downtown area.

T’s the Season—for Loan Defaults.

Whether one would argue that the economy is doing “fine” or it is heading for a crash—soft or hard in nature, what cannot be challenged is the fact that a good deal of debt on commercial properties is coming due in the very near future.[1] In one article by Neil Callanan of Bloomberg, the author noted, along with many other reports, that the amount due in the 2023 and next 2 years is in the range of $1 and ½ trillion dollars.[2]

With this huge debt coming due on commercial properties, what does this mean? If history is any indicator of what will develop, the clear answer is that such due dates create a rush for refinancing of the loans in question. This is the norm. However, what is not the norm is the inability to refinance the loans. Such status results when lenders are not able or are not willing to extend or grant the new loans that are needed under terms that are close to what existed the last time the loans were renewed or when the loan was first granted. This setting is what exists today. That is, as was quoted in a Wall Street Journal article, citing Gregg Williams at Trident Pacific, which is a firm acting as receiver on projects under a defaulted loan:

“What we’re seeing is the unfortunate collision of the most rapid increase in interest rates in a one-year period and the realities of how people work.”[3]

Supporting this same position of concern, in the same article by the Wall Street Journal, citing the research firm of CoStar, the Managing Director of CoStar, Xiaojing Li, stated the position that they estimate “…as much as 83% of outstanding securitized office loans won’t be able to refinance if interest rates stay at current levels.”[4]

What this means is we already are seeing many defaults on existing commercial loans; and, we will see this number growing, absent a major and very positive change in the marketplace that would cause a more positive outlook on the economic position in the market. Such change, if it were to come about, would need to present much lower interest rates, greater loan to value positions, and other favorable terms. This scenario is very unlikely to occur without huge political, economic, and cultural shifts in the marketplace.

Therefore, assuming for purposes of his article that such major alternations do not occur, what are the Business and Societal implications to those involved in the default positions on the existing loans that are or will be non-performing in 2024 or the near future?

There are important financial and related consequences to the broad economy and to entities and individuals involved in such defaults.

The purpose of this Note is to examine current 2024 business and societal issues that are and will be faced by many institutions and individuals in this default setting.

The business issues impact not only the given debtor and creditor on the loan in question, but also others (governments, related activities that rely on the business in question, international issues, and many more).

Large numbers of defaults have far-reaching implications within a society. Will such defaults result in loss of jobs and lack of income for individuals, businesses, and governments? If so, what are the repercussions of such negative results? What is the impact of such results on an international basis? (If the US sneezes, does the whole world—or part of it—catch a cold?)

Knowing that the commercial real estate defaults are occurring at this time, with more on the way as indicated above, we move to the examination of the broad areas of analysis as indicated: Implications to businesses and society, under a setting with many commercial office loan defaults.

The area of commercial real estate does not exist in a vacuum. The success or failure of this office investment area will influence many areas in our society and in business, as discussed in more detail below.

Before moving to the more specific areas of this discussion, it is worth noting the causes of the defaults in 2024 that are now present, with more failures on the way. That is, what is it that caused the higher interest rates, the greater vacancies in the office buildings, the concern by lenders with extending or granting new loans, and other factors that have damaged the office building as an investment class?

Covid19, working from home, changes in lifestyle, crime in the cities, more homeless, more uncontrolled immigration, financial strains on governments, and much more have been part of the catalysts that have reduced the occupancy and rates for office building leases. This decline in occupancy has diminished other business activity for those entities that survive in part through traffic generated by the office buildings, such as retail outlets, parking lots, etc.

With these changes, creating adverse settings which will not be solved soon, the likelihood that this financing issue is of short duration is unrealistic. The solutions employed to eliminate these defaults are at the heart of numerous studies at this time.[5] What is certain is the problem to obtain financing will continue for some time, resulting in defaults and the implications of the defaults as discussed below.

IMPLICATIONS FROM LOAN DEFAULTS

As mentioned, there are many areas in business and society that are impacted because of loan defaults. When examining commercial, office building loans, there are a myriad of people and properties that can be affected when a commercial loan is in default.

Consider a scenario where an investment group is assembled to acquire or build a large office building. Assume the project involves a cost of $300,000,000. Assume the property was financed with a large insurance fund or retirement fund who was willing to loan 70% of the cost of the structure that was being built or used to acquire an existing structure.

This type of setting might also involve a loan or permanent financing that is already in place and the monthly debt service payments are being made. Whether such debt will continue to be paid is in question, given the 2024 rental position of many office buildings.

Assume that there is a 70% debt amount that originated a few years ago, and assume the interest rate was a rate of 4.5%, amortized over 25 years, but with a due date to pay the entire loan at the end of 5 years. The anticipation by the parties was that the loan would either be renewed by the lender, or the owners/debtors would seek other financing to repay the existing loan. Such new debt that would be acquired would be at a rate, so the parties thought, of somewhere close to the initial rate of 4.5%. If the rate environment is such that the new loan to be acquired could be at a lesser rate than the existing rate, this bodes well for the owners/debtors. On the other hand, if the rates are up, the cost to the owners/debtors will be increased as to the interest payments. (Below, we examine the concerns to weigh if the interest rate involves a substantial increase, e.g., a 3%-point increase, moving the interest rate in the assumed setting to 7.5%. Or, what if “no” lenders are willing to make the loan, without regard to arguing over what interest rate might be charged?!)

At the time of the original financing assumed in the example above, the equity portion of the acquisition package might have been 30%. Thus, the project required a loan of 70% and an equity participation of 30%. This 30% might have been acquired by contributions from well-positioned individuals or by institutions. 30% may have been raised by a public or private syndication. Whatever the source of the 30%, there are others involved in the raising of funds on the equity side.

Employing this basic structure for this analysis, there are or could be many parties involved in the acquisition or building of the project in question.

When it comes time for the refinancing of the existing initial loan of 300 million, there are many issues to consider. For example:

- What will be the effective annual percentage rate for the new loan in 2024? It will include the interest rate and any other charges, such as points, administrative costs, and other expenses to acquire the new loan. For ease in this examination and simplicity, the main issue at hand is to consider if a new loan can be obtained, but only at an interest rate of 7.5%. Thus, there is a 3% increase in interest on the new loan, which loan it is assumed might be in an amount of 300 million. (One could simplify the example and assume the initial loan was for interest only payments, resulting in no amortization of the initial loan of 70% of the 300 million, or a net loan of $210 million.) Thus, the debt service on this loan will increase, assuming no amortization of the initial loan, by 3% on $210 million, per year. That is, a 70% loan on a 300 million value is 210 million. The increased rate is 3% higher than the existing 4.5% rate. This means the monthly payments will increase by $525,000. (The total 7.5% interest would be calculated on the amount of $210 million, resulting in a yearly payment of $15,750,000.)

- What other charges or changes may occur on the new loan? The most basic concern is that no lender will be willing to make this loan. Such reluctance may exist because lenders will have their own capital requirements and other concerns to consider in a market where office loans are not favored.

- If the loan is made, what other changes might the lender require? It is possible the lender will require More Equity into the project from the owners/debtors. That is, in place of the 70% loan mentioned above, the lender might require more equity, such as 35% equity. That is, the lender will make only a loan of 65%. In this setting, the additional equity of 5% of 210 million means that the borrowers/owners will have to place another $10.5 million of equity into the project. (This is 5% of the 210 million.)

- What if the lender agrees to loan the 65%, but it is this percentage that is multiplied against the value determined under a current 2024 appraisal of the building? What if the value of the building is now appraised in 2024 at not 300 million, but it is something of a lesser value, such as $240 million? That is, if the building is valued at 20% less than the value of 300 million, the value at the time of the original loan, then the lender might only be willing, in 2024, to loan 65% or 70% of the current 2024 appraised value of 240 million. This means, even at a 70% loan, the lender will only loan a total of $168 million. (At the time of preparing this Note, the 2024 market has many examples where buildings have been reappraised, resulting in many instances of a drop in the 2024 appraised value as contrasted with the value of the building at the time of the initial loan on the building. There are many instances, today, where there are buildings that are showing a decrease in the current, appraised value of 20% or more, such as the example considered in this discussion.[6])

The above are only a few of the changes that might be faced by owners/borrowers when seeking a new or refinanced loan. The financial implications for the ownership group/ borrowing group should be obvious. The investment position is no longer a viable or desirable position for most if not all the investors/ debtors.

Many individuals and entities will be damaged under the assumptions in the above example. In such a setting, there are implications to not only the parties directly involved in the project, but there are huge ramifications to other individuals and entities outside of the project.

Consider some of the parties impacted by the project, but who are not direct owners, debtors, or creditors of the project. A few examples might include various others in the society that may suffer major financial and personal issues when the office buildings cannot be refinanced.

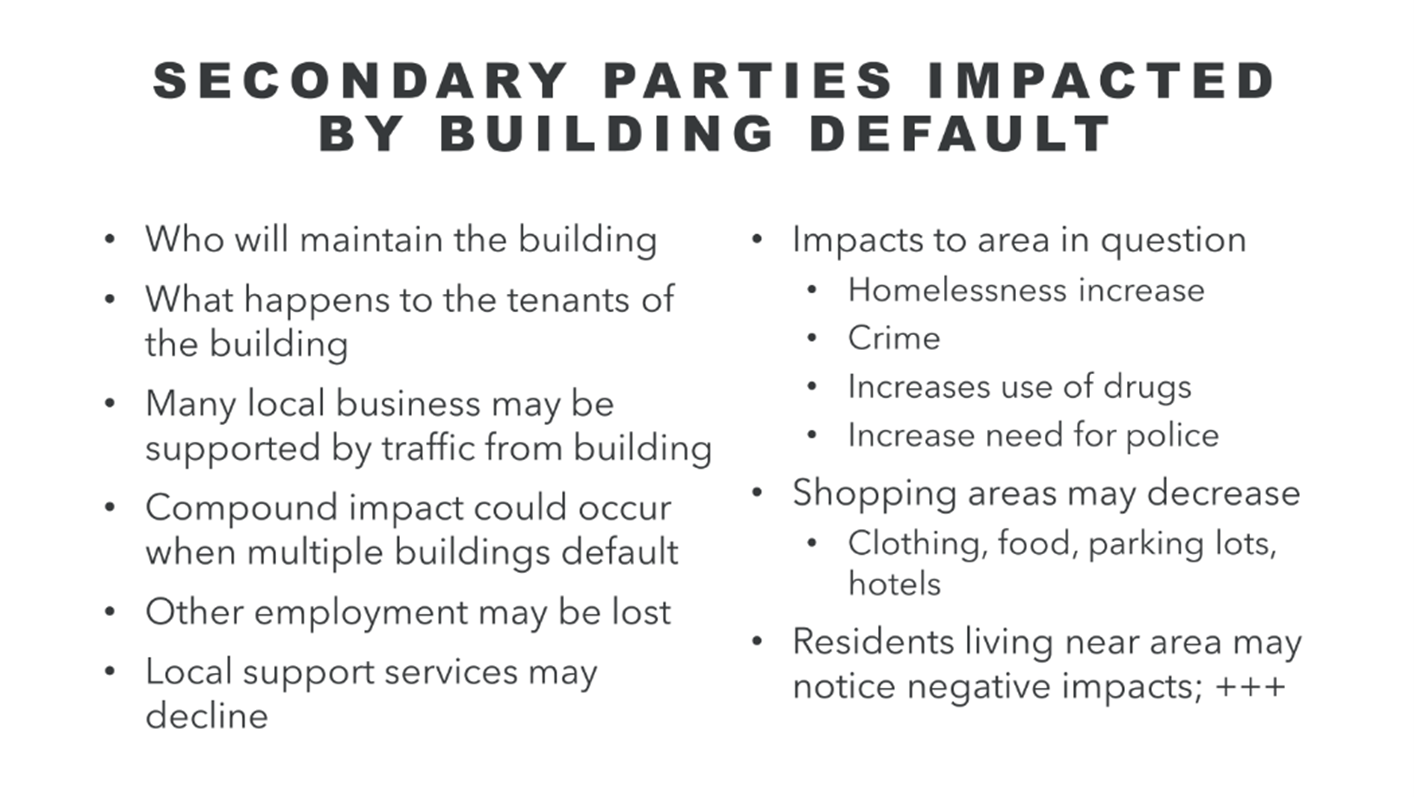

- Who will maintain the building? That is, if the owners of the buildings are in default, and there is no financial recourse to such owners,[7] the existing lender must secure the operation of the building. This means the lender will suffer additional losses, beyond the loan outstanding. If they had to sell the building, if a sale could take place, what price would be obtained after all expenses of sale, upkeep, etc.?[8] If the sales price is less than what is owed to the lender, the lender suffers a loss; thus, those involved with the lender, such as stockholders, suffer a loss.

- What happens to tenants in the building? Will the building be maintained?[9] What happens to tenants that rely on traffic in the building, for their business, such as attorneys, reporters, etc.?

- Are property taxes being paid?[10] In most taxing jurisdictions, the taxing authority may have a priority lien over most other liens. In such instance, if this is correct, the lender must pay the taxes to secure their existing loan position of priority on liens.[11] In some settings with a default, the lender will “walk” and not pursue foreclosure on the property. This is not likely in the example set out above; however, on smaller properties that have other concerns, such as contamination, , the lender may choose to not pay the taxes and the lender may simply abandon the property. If such an event occurs, the local government may find that they “own” the property and thus taxes are not paid. (There can be tax sales of the property; thus, the local government may also be directly impacted by a default.)

- As mentioned earlier, many local businesses may be supported by the traffic from the local building that is now in default in 2024. Thus, small businesses may find that defaulting on the loan on the large building may damage other small businesses that depend on the traffic from the large office building.

- Workers employed in support of the office building may lose work or their job because of the default on the loan in the example given.

- A compound impact may result when this building in question and other buildings are in default. These defaults can have a cumulative impact on the areas in question, such as the downtown area.

- There might be other implications to the area in question, such as an increase in homeless people in the area, increased crime, use of drugs in the area, requirements placed on the city for more services, such as police, etc.

- Other employment may be lost, resulting in more individuals impacted by the default on the loan.

- Local support services may suffer a decline in business. This may include shopping areas for clothing, food, restaurants, parking lots, hotels, drug stores, and many other local businesses that depend on the foot traffic generated from the activity in the building that is now under the defaulted loan.

- Residents living near the building where the loan is in default may find a negative impact on the area in which they live.

- And more….

In summary:

All the above items include both financial and non-financial issues that are important to individuals and entities on a personal and societal basis. Much more could be added to the above discussion as to how a loan default can have broad and important impacts on individuals and entities. Suffice it to say that there are many issues to consider. The discussion now moves to more technical issues on how a default has major, federal, income tax implications to many people involved when there are defaults on real estate loans.

TAX IMPLICATIONS ON A DEFAULT ON A COMMERCIAL LOAN:

The discharge of debt has important tax ramifications. In general, the discharge of debt may cause the generation of taxable income to the person or entity that is relieved of the debt—or part of it—in question. This is under well-established Federal tax law[12] and applies in many states.[13] Under Code Section 61,[14] Congress provided for many items that can constitute gross income. Under Code Section 61 (a) (11), the Code states that gross income includes (unless otherwise provided in the Code) “Income from the discharge of indebtedness.”[15]

Tax considerations are a part of the areas that impact businesses and individuals where loan defaults occur. There are many tax considerations in the United States, on the Federal and state levels, that should be examined in this environment of loan defaults. Most of the tax analysis in this Note is on Federal, not state, tax issues. However, each state law must also be considered when analyzing the tax issues that arise when a loan is in default and property transfers because of such default, be it from a foreclosure, a court order, or other arrangements to settle the debt issues between the lender and the debtor.

This section of this Note addresses many of the circumstances that can generate taxable income[16] where debt is eliminated and those circumstances where even with the discharge of a debt, the Code provides settings where there are exceptions and income is not generated.[17]

As mentioned,[18] there are many considerations when there will be a possible cancellation of a debt. The earlier discussion considered the non-tax issues with the discharge of debt. Continuing with the tax issues, consider the following as to release or discharge of debt.

- Normal Setting of Debt Payoff:

Debt is normally discharged or eliminated in most circumstances when the debt is paid in full. The payment of the debt is made by the seller of property at closing, when the seller provides a deed to the buyer. That payoff, per se, is not the controlling factor in most instances to determine the taxable gain, if any, to the seller. Rather, the seller receives a selling price, after adjusting for expenses, reduces the price by the then adjusted basis of the property, and then determines the net gain or loss to the seller. This is the typical setting, where there is no default.

- Foreclosure or Deed in Lieu of Foreclosure:

However, when the property is transferred and the seller, for example, receives no payment from the lender who is foreclosing on the realty or accepting a deed from the seller in lieu[19] of the lender foreclosing on the realty, there are tax issues to consider.

Federal law, via statute, such as Code Section 61, noted earlier,[20] and case law, must determine if there has been a gain or loss to the seller when the property is transferred, even without having the seller paid any monies.

In this setting, one might assume that there is no gain or loss to the seller. However, such assumption can be faulty in many settings, as discussed, below.

For a simple example, assume the seller purchased a property for 10 million dollars but did not have any funds in to the property, when purchasing the property, either because the purchaser assumed a 10-million-dollar loan or bought the property by borrowing 10 million. (Also, assume the loan is an interest only loan in that there is no amortization of the principal owing.[21]) Assume further that the purchaser depreciated the property over a given period resulting in 1 million of depreciation. Thus, the adjusted basis for tax purposes of the property to the purchaser, who is now selling or defaulting on the loan on the property, is 10 million, less the depreciation, or an adjusted basis of 9 million.[22]

If the seller sold the property for 10 million, one might assume there is no gain or loss as the property was sold for the same price as was paid for the purchase of the building. However, that assumption is incorrect. Why? Because the adjusted basis to the seller is 9 million and the sales price was 10 million. Thus, the tax law under the Code would support the posture that there is a million dollars of gain to the seller. (This issue could also arise when the seller acquires the property with debt and equity, and the seller depreciates the property over time in an amount where the accumulative depreciation exceeds the amount of equity invested in the property.)

Alternatively, if the purchaser did not sell this property, but it was lost in a foreclosure of the property or the seller tendered a lender a deed in lieu of foreclosure,[23] the seller, even without receiving one dollar from the transaction, has gain of the 1 million under the above example.

Again, this result is within the parameters of Code Section 61, among other Sections of the Code.[24] (There are some exceptions to this rule, where taxable income will not apply; however, again, these are exceptions. The normal rule would be that the gain in the example would be taxed to the owner/transferor;[25] see below for a discussion of some of these exceptions.)[26]

What the seller must contemplate when faced with the above setting is when taxable income will apply,[27] even in a foreclosure or deed in lieu setting; and when can– and how can– the seller avoid taxable income in this setting.

There are situations where the above settings do not apply.

Here are a few quick examples.

Discharge of Debt Without Generating Taxable Income

In as much as we have no “debtor’s prison”[28] where one could go to jail for failing to pay debts, even without any issue of fraud or other impropriety, Congress needed to address a setting where one might generate taxable income, yet not have the ability to pay the taxes.

In this setting, under the current law, as noted, the debtor could be relieved of debt (forgiven), which Congress has already said can in some cases generate taxable income. However, this is problematic if the taxpayer does not have any assets to pay the tax.

To address this enigma, Congress passed several laws. Consider the following:

- Gift:

If the taxpayer is owed a sum of money, but the creditor chooses to make a gift of the amount owed, such as X owing Y, the Creditor, the sum of $10,000, but Y states that X is forgiven and does not have to pay Y the money owed, this gift is not subject to a Federal income tax on X.[29] (The gift tax issues are not addressed in detail in this note. However, for more on this issue, see the Footnote.[30]) Of course, this example is a gift and not a sale along the lines mentioned above with loans in default. Thus, only passing reference is made to this issue herein.

- Debt Not Discharged:

If the debt continues, there may not be debt relief and thus taxable income may not be generated. For example, if the earlier example of a debt of 10 million applied, and the basis was 9 million, where the seller of the property surrendered the property or sold the property to the creditor to satisfy 9 million of the debt, with the promise that the debtor would pay the other 1 million in a given period of time, there is no income to the debtor in this setting. The debtor is agreeing to pay the full 10 million; the debtor was not discharged from the 1 million.

- Code Provisions that Eliminate Taxable Income:

The Code has special provisions within it that allow for some exceptions where a debtor, discharged from a debt, nevertheless, does not have taxable income.

One such Code Section, 108, allows for a few settings where taxable income is not generated even when there is a discharge of indebtedness.[31]

Code Section 108 (a) provides for 5 exceptions in this setting where taxable income is not generated, even with a discharge of debt, if the taxpayer can meet the Code Section 108 requirements.

This Section states:

“Gross income does not include any amount which (but for this subsection) would be includible in gross income by reason of the discharge (in whole or in part) of indebtedness of the taxpayer if—”[32]

(The Code then moves to discuss the 5 situations.)

- “The discharge occurs in a title 11 case.”[33] That is, if there is a bankruptcy that comes within the details of this provision, where the taxpayer is in a bankruptcy and does not have assets to pay the tax debt, the taxpayer can be excused from such debt.[34]

- “The discharge occurs when the taxpayer is insolvent.”[35]

This could involve a setting where the taxpayer can show the taxpayer is insolvent, that is, the taxpayer’s assets are exceeded in an amount by debts, yet the taxpayer may not have filed for bankruptcy.[36]

- “The indebtedness discharged is qualified farm indebtedness.”[37]

- “In the case of a taxpayer other than a C corporation, the indebtedness discharged is qualified real property business indebtedness.”[38]

- “The indebtedness discharged is qualified principal residence indebtedness….”[39]

The above areas of Code Section 108 simply illustrate that there are exceptions where, even with a discharge of indebtedness, taxable income may not result. However, if a taxpayer/debtor cannot come within a rule that allows the exclusion of gain generated in a foreclosure or deed in lieu setting, income will be generated as discussed earlier.[40]

“Solutions” to the Office Building Crisis:

Many pundits, investors, lenders, builders, academicians, attorneys, counselors, government bodies, and others have offered “solutions” or suggestions to resolve the current office building dilemma.

Proposals to resolve the current office space glut have ranged from tearing down buildings, especially those Class C (older, dysfunctional buildings), foreclosures and repricing of the property acquired in foreclosures, conversions40 of offices to other uses, such as residential multifamily apartments, condominiums for residential and office uses, other workout arrangements with the investors/owners of the structures and the holders of the existing notes on the buildings, joint ventures between the current owners of the buildings and the lenders on the current buildings, and more.

Knowing the uncertain answer as to when the office space now vacant will be in demand by workers returning to the office, when interest rates will fall, allowing for more favorable financing, and a myriad of other issues, the “solutions” that might allow for solving the office glut and lower rents remains in question.

As mentioned, many suggestions have been floated by lenders, investors, governments,[41] and others. Still, the “answers” remain elusive.

Given more time, some of the options suggested to help resolve this crisis may make more sense than they do today.

The Avalanche of Defaults is Coming!

Without regard to those that will be directly damaged when there are foreclosures on office buildings, such directly damaged parties including but not limited to owners or investors in the building, lenders, tenants, workers related to the functioning of the office buildings, cities that rely on income, sales and other taxes connected with the building and its occupants, there are others in the area of the building under default. Many others that can be caught in the web of injury from the default on the loans in question. Those injured in the fallout from the default are not limited to the owner of the building and the lender. Thus, many parties must consider the damage that results from the foreclosure.

Many building owners, especially those dealing with office buildings, will have a very difficult burden to support the refinancing of existing loans as these loans mature. If the refinancing is not available and a foreclosure occurs, damage can be widespread and include, as noted earlier, many people who are not owners or lenders involved in the building in question.

As mentioned,[42] many loans, the total loans being in the Trillions of dollars, appear to be approaching their maturity.

The financing of a new loan, that is, the underwriting to acquire a new loan, necessitates supporting income, coverage ratios, interest rates and other terms that cannot often be met by many current office building owners. Thus, many defaults will likely be present. In such settings, not only are there the direct financial losses for investors who may lose their capital, but, rubbing salt in the wound of the investors, such parties may learn that they not only lose part or all their investment, but they may also have to provide additional funds because of the discharge of indebtedness causing taxable income to them.

Many of the loans in default in 2024, or moving toward a default position, will not be cured. Therefore, many, if not all the parties mentioned earlier, such as tenants, workers, cities, etc., may find that they, too, may suffer financial, personal, and societal losses when a foreclosure occurs.

REFERENCES

[1] There are many sources that have been cited to support this position of the debt that is coming due in the current and next few years. See, for example, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-04-08/a-1-5-trillion-wall-of-debt-is-looming-for-us-commercial-properties#xj4y7vzkg The Wall Street Journal has indicated the same number as coming due in the next 3 years, citing its source as Trepp, a data source. See https://www.wsj.com/articles/interest-only-loans-helped-commercial-property-boom-now-theyre-coming-due-c3754941

[2] Id.

[3] https://www.wsj.com/articles/interest-only-loans-helped-commercial-property-boom-now-theyre-coming-due-c3754941

[4] Id.

[5] This issue is discussed below. See infra Footnote 41.

[6] See Supra Footnote 1.

[7] Often the loans of this type in the example given, especially as to the size of the loan, are non-recourse loans, where the lender will look only to the real estate to support the obligation owing to the lender; often there is no personal liability to any individual or entity that is involved as an equity owner in the project. Thus, it is not unreasonable to assume that the lender who is owed the debt in question on the structure must face the concern with not only attempting to regain the amount owing to it, but also recognize that if there is a foreclosure on the structure in question, or other settlement, such as a deed in lieu of foreclosure, there are nevertheless additional costs and on-going expenses that the lender would incur in acquiring the building and holding as real estate owned (REO) by the lender.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Even if property taxes have been escrowed with monthly payments, there is the concern with the additional taxes that will be incurred when the lender acquires the building in a foreclosure or otherwise.

[11] Such tax lien priorities are common in most states.

[12] See Internal Revenue Code of 1986 as Amended, herein sometimes referred to as the Code or the Internal Revenue Code. In this instance, specifically Code Section 61.

[13] Many state income tax laws follow the Federal income tax laws in many areas, such as what items constitute income for tax purposes. These states are often referred to as “piggy-back” states when there state law is tied to the Federal income tax laws.

[14] Code Section 61.

[15] Code Section 61 (a) (11).

[16] Some of these settings are described below. For more detail, see Levine, Mark Lee and Segev, Libbi Levine, Real Estate Transactions, Tax Planning, Chapter 21 (Thomson/Reuters/West) Volume 1 (2023).

[17] See, for examples, where income may not be generated, Code Sections 1038 and 108, which are discussed, below.

[18] See Supra Footnote 16.

[19] A deed by an owner/seller to the lender often saves a good deal of time and expense as opposed to the lender undertaking a foreclosure. It may also be a better public position for a lender as well as for the debtor/owner. For more on this issue, see Rajinder K. Saini, Alexander C. Berger and Trevor Hoffmann, “To Deed, Or Not To Deed (That is the Question): The Pros and Cons of a Deed in Lieu,”

As explained in this article, there are many other considerations that should be weighed before a lender or debtor undertake a deed in lien of a foreclosure. For example, the in lieu position should also consider other liens on the property, other liabilities, timing of the deed, tax issues and much more.

[20] See Supra ———————-

[21] Interest-Only Loans Helped Commercial Property Boom. Now They’re Coming Due.

Landlords face a $1.5 trillion bill for commercial mortgages over the next three years. Konrad Putzier (June 6, 2023).

[22] See Code Sections 1012 and 1016 as to the basis and adjustments.

[23] See Supra for the discussion on a “deed in lieu.”

[24] As to how much income is generated when there is a discharge of debt, see the Levine and Segev text, Chapter 21, cited Supra Footnote 16. The amount of income generated, based on case law, seems to depend in many instances as to whether the fair market value of the real estate was more than the adjusted basis of the taxpayer as to the foreclosed property. However, this can vary in some cases by looking to the difference of the taxpayer’s adjusted basis as compared to the debt being discharged. See the Levine and Segev text on this issue.

There can also be recapture of depreciation in the foreclosure sale, where gain is generated. See Code Section 1250 and the discussion of this issue in the Levine and Segev text as cited herein.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] The structure of the law in the United States does not provide for a criminal offense simply because a business fails. (This position assumes no impropriety or improper action was undertaken by those involved in the business that fails.) Under the Constitution of the US, there are specific provisions for discharge of debt, allowing for a new start, without a criminal sanction for loss of funds because of the failure of the business. See the United States Constitution, Article I, Section 8, providing for Congress to enact authority on the issue of bankruptcies.

[29] See Code Section 102 and Treas. Regs Section 1.61-7.

[30] For a detailed examination of this type of gift tax issue, see the Levine and Segev text, Chapter 41, cited Supra, Footnote 9. See also Code Section 2503.

[31] Code Section 108. Rev. Rul. 2016-15.

[32] Code Section 108 (a) (1). For more detail on this issue, see Supra Footnote 9. For a detailed discussion of many of these and related issues, see the Levine and Segev text, Chapter 21, Supra Footnote 16.

[33] Code Section 108 (a) (1) (A). See also, Hartman, Paul J., “The Dischargeability of Debts in Bankruptcy,”15 Vanderbilt Law Review 1 (December 1961).

[34] Id.

[35] Code Section 108 (a) (1) (B). The potential discharge is limited to the insolvency.

[36] Id. See also, Kahn, Jeffrey and Kahn, Douglas, “Cancellation of Debt and Related Transactions,” 69, Vol 1, Tax Lawyer 161 (2015).

[37] The detail of this farm area discharge is outside the scope of this discussion. See the references in Code Section 108 (a) (1) (C) and in the Levine and Segev text cited Supra, Footnote 9, with emphasis on Chapter 21 of that text.

[38] See Code Section 108 (a) (1) (D) and the Levine and Segev text, cited Supra, Footnote 9.

[39] See Code Section 108 (a) (1) (E). This discharge must occur regarding the principal residence. Thus, it is not focused on the area of this Note as to commercial real estate. Further, specific time frames must be met to come within this provision.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/108#:~:text=If%20any%20loan%20is%20discharged,which%20is%20not%20qualified%20principal

[40] See Supra Footnote 7 as to recourse and non-recourse debt involving taxable income on default on a loan.

[41] In a recent publication issued by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) entitled Evidence Matters, HUD focused on “Office to Residential Conversions” (Fall 2023). In this publication, HUD, via comments by the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Policy Development, Brian McCabe, stated that “Office conversion can help to increase the supply of housing in neighborhoods where it is desperately needed….” He also commented that converting underutilized office space to residential use has additional benefits.” The Secretary then cited the concern with vacant office buildings and the damage such buildings can cause to cities and businesses in the area of such vacant office buildings. For more on this issue by HUD, see www.huduser.gov/forums. Many cities are also active in this conversion approach, along with considering subsidies and credits for such conversions.

[42] See Supra Footnote 1.

@Who is Danny/Shutterstock.com

@Who is Danny/Shutterstock.com