Editor’s Note: This article was written prior to the events of March 29, 2017, when Prime Minister Theresa May triggered Article 50.

As a former imperial capital, London has had global significance for about 300 years, but over the last 30, it has seen particular success. Although its global roles as a financial center and business management hub are generally held up as the key reasons behind its success, there are many more qualities that make London a pre-eminent global city.

For some, the recent Brexit vote was a signal from the rest of the country that London’s dominance needs to be kept in check, that the financial industry should not be given preferential treatment or incentives, and other industries and regional centers need to get a larger slice of the investment ‘pie.’ Seven months on, we are starting to see whether these effects will actually materialize. However, in the long run, the impacts of Brexit will depend less on the immediate effects of economic uncertainty (which is likely to span at least two years whilst negotiations take place1), but on the ongoing ability of London to attract and support global business. In this article, we explore what the core strengths of London are, before assessing the current and likely impacts of Brexit in the longer term.

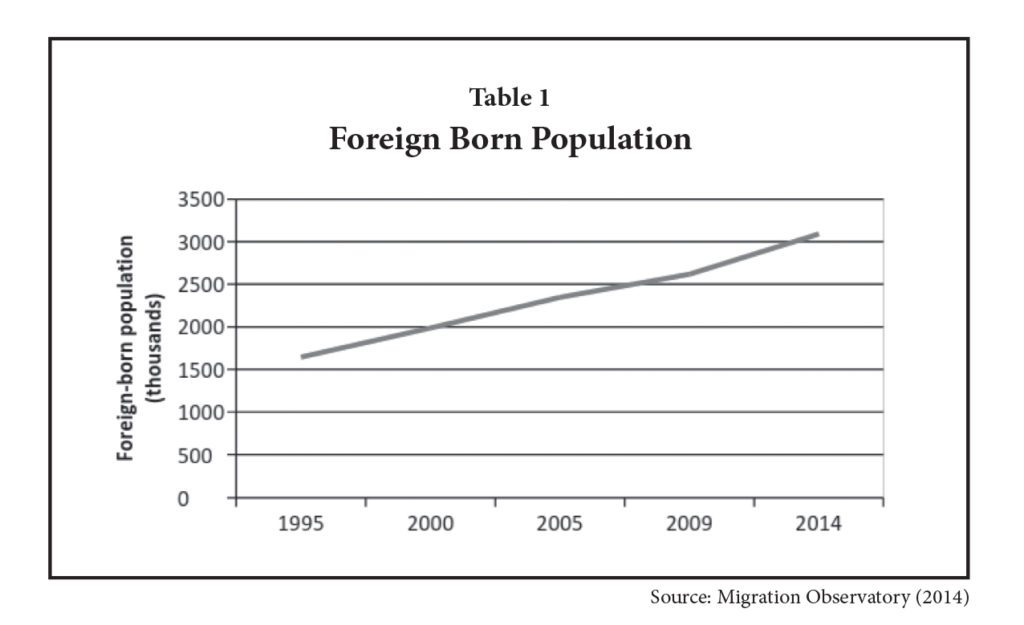

The story of London as a global financial center can be traced back several centuries, but only after the ‘Big Bang’ of the 1986, did its role in international banking really take off. For instance, between 1981 and 1989, employment in banking, finance and insurance in London increased by 38 percent.2 This increase is partly attributable to the growing presence of foreign, particularly U.S., banks in London, which has now reached over 250, including Goldman Sachs, and UBS. The foreign-born workforce in London has correspondingly increased to the extent that 36.7 percent of London’s population were born abroad,3 providing a culturally diverse workforce.

Not only is the population culturally diverse, but highly skilled. In London, 56 percent of economically active people have a degree, a figure which rises to an astonishing 77 percent in the borough of Wandsworth.4 The next most highly qualified city in Europe is Oslo, where 54 percent of the population is qualified to degree level or higher.5 This is no surprise, given London’s ability to attract talent and the fact that London is home to over 60 universities and colleges, of which University College London, Kings College London, Imperial College, and London School of Economics are known internationally as particularly outstanding. Despite this, according to the Institute for Public Policy Research,6 labor market demand in 2022 for high-skilled jobs in London is expected to outpace supply.

Given that such a large percentage of employment in London is in the services sector (87.9 percent),7 and 56 percent of vacancies are in occupations that require a degree-level of training or higher, it is hardly surprising that the labor market in London is thirsty for educated individuals.8 It is encouraging that employment in the FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate) sector as a percentage of the total is below 2007 levels, indicating that London’s economy has since rebalanced, specifically towards greater employment in the professional services, real estate and scientific/technical sectors.9 Creative industries have also flourished around Soho, Shoreditch, King’s Cross and Hammersmith, contributing around 16.3 percent of the total jobs in London.

As a tech hub, London has grown in stature, with 23 percent of investors believing that London has the right environment to produce the next technology giant, compared with 10 percent for Berlin.10 This is supported by research into European technology clusters, which has shown that London has the most to offer compared with its European competitors in terms of employment in this sector, ability to generate start-ups and new patents, and attractiveness for technology students and graduates.11 This is especially true for the ‘fintech’ industry, which has thrived in London thanks in part to the surplus of financially savvy yet unemployed professionals in the capital in the years immediately following the last financial crisis.12

Not only is there a variety of industry, but a concentration of top-level management. This is indicated by data from the Global and World Cities network, which places London at the top of the global city connectivity ranking, measuring cities according to the presence and importance of professional services firms’ headquarters. According to Deloitte (2014), London hosts 40 percent of the European headquarters of the world’s top companies.

London is not only a place to work, but also to play. For off-duty Londoners, there is a vast array of cultural, sporting, leisure and retail options to choose from. The West-End regularly tops international rankings for shopping and the current weakened value of the Sterling has boosted sales for luxury retailers, with Harrods reporting record sales last year. For entertainment, there are over 6,000 restaurants to enjoy, of which 65 are Michelin starred, before an evening at one of the 241 theaters.13 In terms of sport, there are 14 major venues, including the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and Wembley stadium. For those more culturally inclined, there is a choice of 300 museums, of which the British Museum is consistently ranked among the best in the world. Without adopting the tone of a tourist brochure, it would be fair to say that London’s wealth is not solely a product of the global ranking of its financial center.

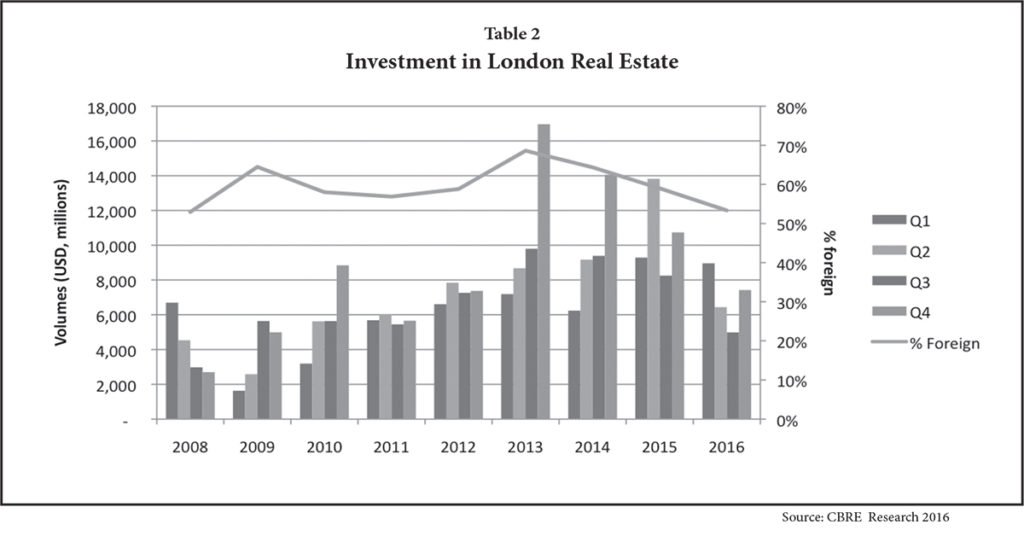

In terms of real estate, London has three core strengths: liquidity, size and transparency. Total investment in 2016 was approaching $28 billion, of which over 50 percent was accounted for by foreign investors.

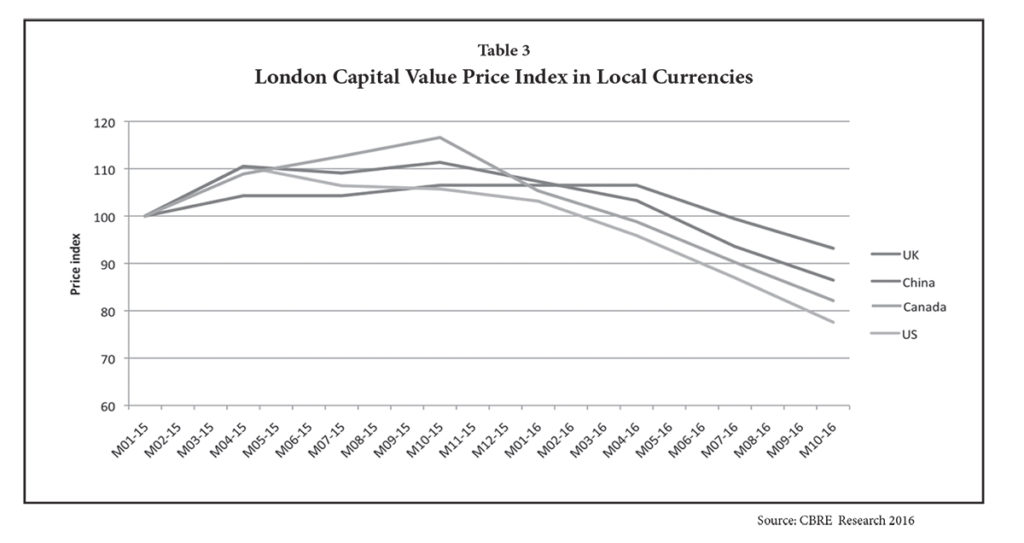

As shown in table 3, the lowered relative value of the pound to other currencies has rendered London real estate comparatively attractive in recent months, which is one explanation for the relatively robust volumes of Asian capital channeled towards London real estate in Q3 last year.

With average returns of 10.8 percent since 2000, and a standard deviation (risk) of 14.5 percent, it is easy to see why London has regularly topped the CBRE EMEA Investor Intentions Survey as a target for investors.

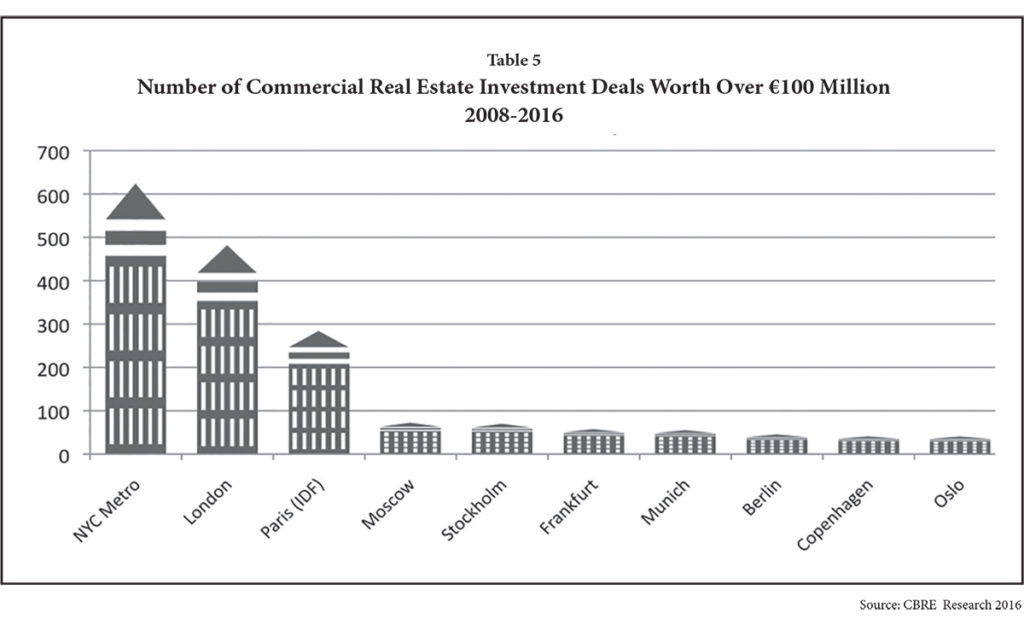

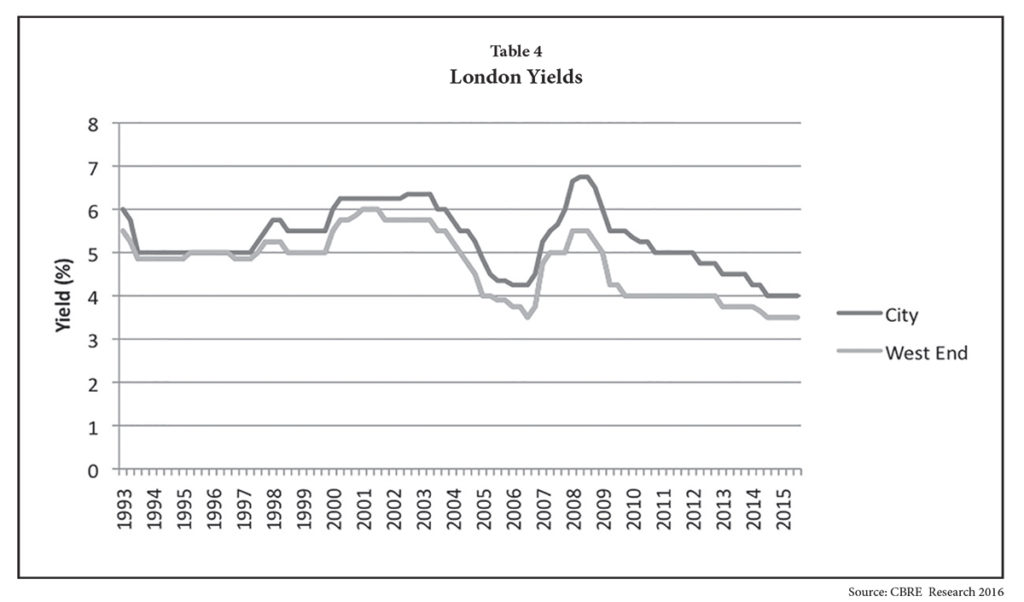

In addition, income returns (i.e. yields) have been fairly stable over time, as shown in the graph below. Despite comparatively weak figures in Q3 this year, there is a long way to go before investment levels, especially cross-border investment, reach a level comparable to any other European city. Part of the reason for this is that London offers a highly liquid market for large lot-size investments. For this reason, London stands head and shoulders above its European competitors for the number of deals over €100m since 2008 (see Table 5). This process is greatly facilitated by a transparent legal system and secure title procedures.

London Post-Brexit — What Has Happened so Far?

Pre-Brexit, the general consensus was that leaving the EU would harm London’s economy, although the extent of this was debated. This was not unreasonable, as uncertainty across business typically affects investment behavior and the economy as a whole. Now that seven months of data are available, we can start measuring the extent of the impact. Since the vote, UK GDP has increased by 0.6 percent, ahead of the 0.3 percent that analysts predicted. The ‘Citi Surprise Index,’ which measures the extent to which actual economic indicators exceed expectations or not,14 also shows that economic performance has been beating expectations. This is reassuring, though it must be remembered that Article 50 has not yet been served and there is still a significant amount of change to come.

So far, the post-Brexit referendum era has indeed been characterized by uncertainty about economic policy. This has translated in the occupier market to a considerable easing in take-up, combined with an uptick in vacancy in Central London offices from 2.3 percent in 2015 to 4.2 percent in January 2017. Of those who have taken space in January 2017, 27 percent were from creative industries, with banking and finance in second place, constituting 24 percent of take-up. Again, this demonstrates that demand for London office space is more diversified than before the 2008 crisis, when 40 percent of take-up of new space came from the banking and finance industry, suggesting there is greater resilience in the market than before.

Market response to the Brexit vote can be measured in terms of active demand for commercial space. Active demand for Central London offices has shown surprising strength in January 2017, at 7.4m sq. ft., compared to 7.1m sq. ft. in December 2016. It seems that London’s fundamental attractiveness as a location for business, as outlined earlier, is capable of sustaining demand in the aftermath of Brexit.

The investment market has seen a less positive response, with transactions at their lowest level since 2011. Since June this year, commercial property capital values not only in Central London, but in New York and San Francisco have declined. This would suggest that the advanced stage in the economic cycle has a role to play as well as the effect of the Brexit vote.

15

15

Scenarios

At present, every week has a new twist to offer in terms of political sentiment and where this may leave the UK in a post-Brexit referendum world. However, in general, there seem to be two likely scenarios:

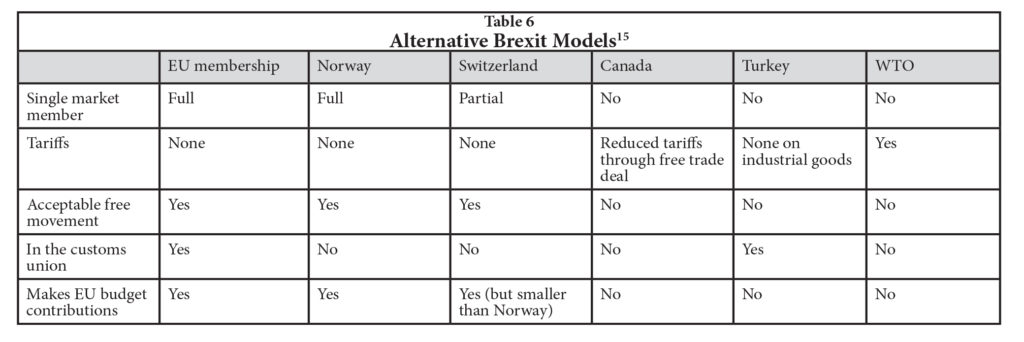

A ‘soft’ Brexit — this would look something like the Norwegian model (see table below), whereby access to the single market is retained, but the UK would no longer be a member of the EU and would not have a seat on the European Council. Goods and services would be traded with the remaining EU states on a tariff-free basis and financial firms would keep their passporting rights to sell services and operate branches in the EU. Britain would remain within the EU’s customs union, meaning that exports would not be subject to border checks. In this scenario it is likely that the UK will continue to make contributions to the EU in return for market access and/or passporting rights.

A ‘hard’ Brexit — this would involve leaving the single market entirely in order to prioritize controlling immigration and have a relationship based — at least initially — on World Trade Organization rules.

While neither outcome is certain at present, Prime Minister Theresa May’s recent Conservative Party conference speech was taken by many as favouring a ‘hard Brexit’. This would imply the UK losing access to the single market, and accompanying passporting rights for the financial sector in exchange for control over movement of labor. There has, however, been no serious suggestion that EU migrants currently living in the UK will be required to leave.

According to The Economist magazine, if a ‘hard Brexit’ does occur, an estimated 75,000 jobs could be lost from London’s financial center, with a third going to the continent, a third to New York, and the rest being lost altogether.16 This does not bode well for the jobs in professional services, many of which are located outside of London, which form part of the supporting infrastructure for London’s financial district. In addition, a tighter immigration policy might be harmful to the tech industry, which relies on easy availability of highly-skilled labor, often from Eastern and Central European regions.17 However, if London’s financial district successfully shifts its focus from servicing EMEA Capital Markets to Emerging Markets, especially those in Asia, this could pave the way towards a renewal of the finance industry following any initial job loss. London has proved itself quite resilient to major political changes over its history!

Construction and development can also be expected to be negatively impacted in the short term. Those developments which have not yet started on site face delays until the level of uncertainty about future demand for space in the economy becomes more certain. In Central London, over 6m. sq. ft. of office developments were completed in 2016, the highest total in over ten years, and a similar level in 2017 — but as less than 3m. sq. ft. is due to complete in 2018 and 2019 has started on site, it is unlikely that we can expect much more than this to come onto the market in these years. The resulting supply restrictions will serve to hold rents up in this period.

For the residential sector, development is more likely to show resilience in the short term for the simple reason that housing in London has been in chronic undersupply over an extended period of time. Development will also receive a boost from the £2.3 billion Housing Infrastructure Fund, intended to help address this shortage in areas of high demand announced by the Chancellor in this month’s Autumn Statement.18 Longer term, development prospects will depend on the future state of the economy but also on the costs of construction.

In terms of investment, while there is continued uncertainty around the outcome of the Brexit negotiations, investors will continue to act with caution. The extent of this uncertainty effect, however, is highly complex to predict with confidence. As 68 percent of investment into Central London over the past eight quarters was accounted for by international investors, London is, in theory, highly vulnerable to a drop in international confidence. Yet it must be remembered that out of this figure, only 13 percent originated from European investors, indicating that it is their outlook that will have most impact on overall investment volumes. It should also be noted that the biggest source of European money into London was Norway, which is itself not in the EU.

It is worth remembering that there are some ‘silver linings’ to be found within a ‘hard Brexit’ cloud. A weaker pound resulting partly as an effect of the uncertain economic climate makes London a more attractive tourist destination, and the boost to retail sales, especially in the luxury sector, has already been felt. With 31.5 million people visiting the capital in 2016,19 London is already ranked among the very top few tourist destinations in the world, and in the month after Brexit, tourist spending increased by 7 percent.20 In addition, freedom from certain aspects of the EU’s regulatory regime, such as setting a cap on bankers’ bonuses, could have the effect of encouraging the industry to stay in the UK.

As to what the broader rebalancing of London’s economy could involve, it is clear that London has a series of core strengths that will endure, whatever shape Brexit will take. These include its diverse and skilled employment base, increasingly diversified and entrepreneurial services and tech sectors, leisure possibilities and cultural heritage. For these reasons, even under a ‘hard Brexit,’ a recent article in the New York Times comparing European cities as potential new locations for the financial sector found London to be the most attractive. This conclusion was drawn based on an analysis of the regulatory environment, especially regarding employment; transportation and communications infrastructure; availability of prime office space and luxury housing; schools; restaurants, English language facility; and cultural offerings.21

According to these measures, the next best city for the financial sector would be Amsterdam, which offers the attractions of culture, communications and good housing stock, but fails to satisfy the need for a relaxed regulatory environment on employment. It seems that there is no ready panacea in Europe for the financial sector to fly to, even with cities falling over each other in a scramble to seduce industry away from London. Most commentators think that a post-Brexit London will have even lighter touch regulation, which is highly attractive to the financial sector.

Ultimately, there are questions over London’s continued ability to generate jobs and attractive returns in a post-Brexit economic environment. Whilst Brexit has, and is likely to cause, a short-term ‘wobble,’ London’s key attributes will provide the basis for its resilience in the long-term.

Endnotes

1. Gibson, M. and Blake, N. (2016) “The Long Goodbye,” https://researchgateway.cbre.com/Layouts/GKCSearch/DownloadHelper.ashx ↩

2. Bank of England (1989) Quarterly Bulletin, available online at: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/archive/Documents/historicpubs/qb/1989/qb89q4516528.pdf ↩

3. Migration Observatory (2014) “Migrants in the UK: An Overview,” http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migrants-in-the-uk-an-overview/ ↩

4. London Datastore (2015), https://data.london.gov.uk/ ↩

5. Eurostat (2016), http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database ↩

6. IPPR (2016) “Jobs and Skills in London,” http://www.ippr.org/files/publications/pdf/london-skills_Apr2016.pdf?noredirect=1 ↩

7. London Datastore (2015), https://data.london.gov.uk/ ↩

8. IPPR (2016) “Jobs and Skills in London,” http://www.ippr.org/files/publications/pdf/london-skills_Apr2016.pdf?noredirect=1 ↩

9. London Datastore (2014), https://data.london.gov.uk/ ↩

10. EY’s Global Investment Monitor (2016), http://www.ey.com/gl/en/issues/business-environment/european-investment-monitor ↩

11. Williams, R. (2015) “London’s technology sector attracts greater investment than ever before,” http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/technology-topics/11509979/Londons-technology-sector-attracts-greater-investment-than-ever-before.html ↩

12. KPMG (2016) “10 reasons why London is becoming the Fintech capital of the world,” http://www.kpmgtechgrowth.co.uk/fintechcapital/ ↩

13. “Almost twice as many people visit the theatre than attend Premier League games,” The Telegraph [online], available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/11001177/Almost-twice-as-many-people-visit-the-theatre-than-attend-Premier-League-games.html ↩

14. Bloomberg (2016) “Pound Spurred by Fear of the Future Shrugs Off Good News,” http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-10-28/pound-spurred-by-fear-of-the-future-shrugs-off-good-news ↩

15. BBC (2016) “Brexit: What are the options?,” http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-37507129 ↩

16. The Economist (2016) “From Big Bang to Brexit” (October issue) ↩

17. Gibson, M. and Blake, N. (2016) “The Long Goodbye,” https://researchgateway.cbre.com/Layouts/GKCSearch/DownloadHelper.ashx ↩

18. Hammond, P. (2016) “Autumn Statement,” http://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/11/23/autumn-statement-chancellors-speech-full/ ↩

19. The Guardian (2016) “London visitor numbers hit record levels,” https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2016/may/20/london-record-visitor-numbers-2015-31-5-million ↩

20. The Guardian (2016) “Tourist spending in UK surges following pound’s Brexit slump,” https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/aug/22/tourist-spending-uk-surges-following-pounds-brexit-slump ↩

21. Stewart, J. (2016) After “Brexit,” Finding a New London for the Financial World to Call Home,” http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/01/business/after-brexit-finding-a-new-london-for-the-financial-world-to-call-home.html?_r=0 ↩

Photo: Matt Gibson/Shutterstock.com

Photo: Matt Gibson/Shutterstock.com