It is now nearly a quarter-century since the adjective ‘disruptive’ gained currency as a positive value, rather than referring to its prior pejorative meaning of ‘disintegrative’ or ‘misbehaving’. The popular embrace of ‘disruption’ as an engine of forward economic change dates from a 1997 book by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma.1 In a way, this adoption of a stark metaphor to characterize progress is reminiscent of another Harvard professor, Joseph Schumpeter, who coined the phrase ‘creative destruction.’2 It is the same spirit as a venerable revolutionary slogan, ‘You cannot make an omelet without breaking some eggs,’ dating to 18th century France and popular in the civil unrest in the United States during the 1960s.3

At its best, this line of thinking reflects a willingness to discard comfortable but unproductive ways of doing things in favor of an innovative leap ahead. At its worst, however, the concept can become an apologia for mischief that covers the very high failure rate of economic experiments.

The incremental alternative of sustainable innovation has garnered fewer headlines over this last quarter century or so, but was at the heart of a previous approach to successful business. That approach focused on the concept of ‘continual improvement,’ a management philosophy most associated with W. Edwards Deming, whose advisory work with Japanese companies was widely credited with accelerating the post-World War II resurgence of the Asian economy.4

The pedigree for this incrementalist approach goes deep in history. Indeed Albertus Magnus, the 13th century philosopher, made a point that change typically moves through a sequence of intermediary steps. The great natural scientist Carl Linnaeus (18th century) gave us the pithy Latin statement natura non saltum facit (“nature does not make leaps”), which inspired Darwin a century later to trace the path of evolution in The Origin of Species. The founder of modern economics, Alfred Marshall, used this Latin phrase as the epigraph of his 1890 Principles of Economics, a text which laid out fundamental economic concepts still considered relevant to understanding economic utility, investment returns, supply and demand, and competition in the marketplace.5

Considering the Disruption of the Coronavirus Pandemic

One of Marshall’s key insights was that economics was not merely a study of wealth, and the activities that go into the creation of wealth. Rather, he considered economics as the study of human beings and their attainment and use of the material elements of well-being. Earning and spending money, he thought, found their interpretative context in the satisfaction of certain necessities of life, most particularly food, clothing, and shelter.

There can be no doubt that the Coronavirus and its active disease manifestation, COVID-19, have caused a major economic disruption. It may be thought that this disruption is different in kind from the examples considered by Christensen and Schumpter but, nevertheless, their thoughts are relevant to our economic situation and to the consequent conditions we find in the real estate markets. Moreover, the temptation to find a quick fix, a kind of leap, is especially strong amongst policy makers right now, and so the systematic perspective of Marshall can be a healthy corrective to some of the ‘magical thinking’ being applied to the restoration of the U.S. economy.

First, let’s look at the ways that the current economic downturn is properly called a ‘disruption.’ Over the years, my commentary has alluded to the five primary kinds of change we normally consider in real estate: cycles, trends, maturation, change of state, and disruption.6 Of these basic forms of change, three are ‘continuous’ change – cycles, trends, and maturation – and two – change of state and disruption – are ‘discontinuous.’7

Much of the standard economic commentary refers to the present condition as a recession. But that is not exactly accurate, if recession is fundamentally considered to be a natural, predictable phase of the business cycle. The danger in that way of thinking lies in the continuous and self-correcting characteristics of the business cycle, as understood by macroeconomics.8 In such a view, recessions – economic contractions that are widespread and of significant duration – are caused by imbalances in production or consumption, with those imbalances adjusted either by the mechanism of market prices, or by the interventions of fiscal or monetary policy. This is ‘continuous’ change that fits the pattern of the eight recessions I’ve experienced during my working career. But it does not accurately describe what is going on in 2020, nor what is likely to be transpiring over the next year or two.

To state the obvious, the economic downturn was triggered by a public health crisis, remains linked to that public health crisis, and the economic future will be shaped in response to that public health crisis. In other words, we should not be expecting economic self-correction to lead us into recovery and then into expansion. Virtually all economic models are predicated on a theory (and equations) anticipating a cyclical return to equilibrium. But just as no model forecast the current crisis, we should not place much confidence in forecasts expecting market forces to restore America’s economic momentum. As a lesson in humility learned by excessive reliance on econometric models, we can do no better than re-read Alan Greenspan’s Foreign Affairs essay, “Never Saw It Coming,” on the Global Financial Crisis (November/December 2013).9

Setting Sights on a Vibrant Future, Not a ‘Return to Normal’

At the time of the Great Depression, in the 1930s, America and the world faced a similar economic cataclysm, one which appeared intractable to either a “wait for the markets to correct” approach or to then-conventional policy approaches, such as protective tariffs to shield domestic industries from international competition. The solution was not to look backward toward re-creating the Gilded Age of the Roaring Twenties. Over time, rather, a series of important changes were introduced by a succession of U.S. presidents (Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower) that broke with past practices and laid the foundation for a half-century growth.

Let’s take a look at what a look forward on the economy might entail, if we were to use the tools and the insights of both approaches of disruption/innovation and of incremental building on historical trends and examples.

Employment

The plunge in employment since March 2020, when the U.S. economy locked down against the pandemic is of historic proportions. As of April, the year-over-year job loss tallied by the Bureau of Labor Statistics exceeded 20 million, or 13.4 percent of total employment. Even with regional economic re-openings, by August the number of employed workers was down 10.2 million on a twelve-month comparative basis, or 6.8 percent.10

While month-to-month figures look more encouraging, with 10.3 million jobs regained from the April trough, momentum has been slowing. In July, 1.73 million added jobs amounted to just 36 percent of June’s 4.8 million gain. August’s gains were even slower, at 1.37 million jobs, and one quarter of those jobs were temporary census workers, tempering enthusiasm for the drop in the unemployment rate to 8.4 percent. The labor force participation rate remains slack at 61.7 percent, with seven million persons not actively looking for jobs and therefore excluded from the denominator used to calculate the official U-3 unemployment rate. Total unemployment (U-6, which accounts for those marginally attached to the labor force and those working only part-time for economic reasons) remains very elevated at 14.2 percent.11

Jobs are reported on a “net” basis, of course. Initial unemployment insurance claims continue to flood in, with August 1st marking the 20th consecutive week of more than one million such claims. For the balance of August, initial claims averaged 974,000 per week. The number of workers receiving relief was 15.4 million, on average, for the four full weeks of August.12

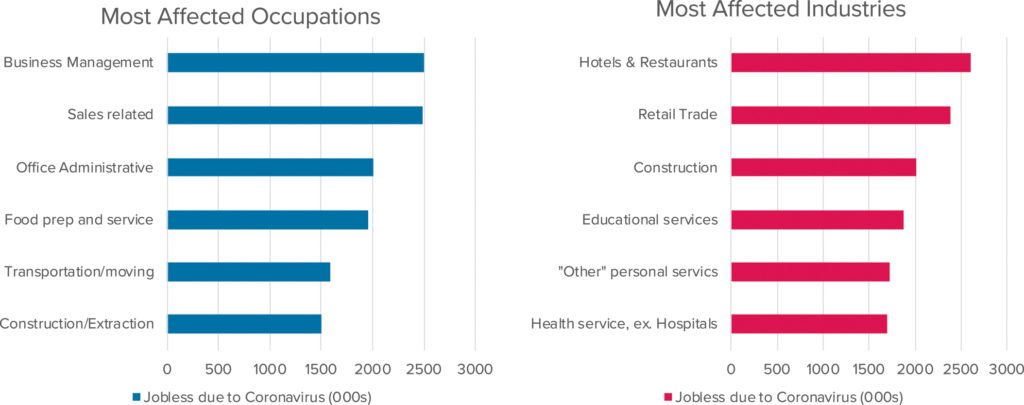

The distribution of job losses, meanwhile, is vastly uneven across the economy, as seen the chart “Hardest Hit Sectors.” The critical take-away from these Bureau of Labor Statistics data is that the headline news about job losses as concentrated in a few industries such as hotels, restaurants, and retail stores, large employing low-wage workers, gives a very incomplete picture of the labor force impacts. Millions have been laid off in a variety of economic sectors, and across a wide range of skills.13

Hardest Hit Sectors Through June 2020

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Concern is growing that a significant proportion of the job losses may be permanent as the downturn lengthens. Businesses that were sustained by the relief package passed by Congress in the Spring are now finding those supports expiring. Consequently, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (a private organization) reports that 58 percent of small business owners find themselves at risk of closing permanently. This has broad economic ramifications, as the U.S. Small Business Administration (a government department) estimates that firms employing fewer than 500 employees account for 44 percent of the nation’s economic activity.14

The upshot is a mixed story. The bad news in the employment picture should not be minimized.

However, slack labor resources can, under innovative policy management, become a Schumpeterian opportunity to redeploy those resources creatively to address national needs in infrastructure, education, and healthcare. The conclusion of this essay will address that opportunity.

What the Capital Markets – and the Fed – Are Telling Us

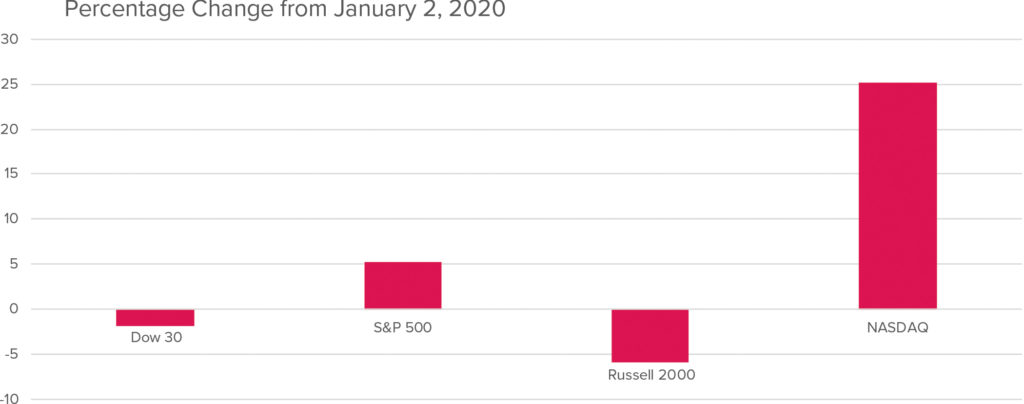

It is a commonplace maxim amongst economists that “the stock market is not the same as the economy.” Yet investor preferences do give a meaningful glimpse at economic expectations. The various indexes tracking the equities markets describe decidedly uneven results for the year 2020, thus far.15 On a positive note, all the major indicators have rebounded sharply from the initial Coronavirus shock that sent them plummeting in March. The Dow 30 (popularly still referred to as the Dow-Jones Industrial Average)16 is still down 1.9 percent since the start of the year, though, reflecting the drag of several of its components tied to transportation, heavy equipment, retail, restaurants, and entertainment. The Russell 2000, a broad index of small-capitalization stocks, has fared even worse, posting a 5.9 percent decline from early January to mid-August.

Equities Markets Expect Mixed Performance Overall, But Strong Tech Growth

Source: Yahoo Finance, data as of August 24, 2020

The S&P 500, on the other hand, is up 5.3 percent, a good sign for the large capitalization stocks representing $27 trillion listed on U.S. exchanges. The S&P performance reflects its mix of firms, with a significant weighting of financial firms, technology giants, and consumer brands, and has consistently produced annualized returns in the 11 to 15 percent range over the past 50 years.

Perhaps more importantly, the NASDAQ composite index, heavily weighted toward larger information technology firms, is leading with a 25.2 percent gain since the start of 2020. Admittedly, the NASDAQ has been the most volatile of the equities indexes, partly owing to its industry concentration limiting the hedge of diversification. That weighting, however, is benefiting this sector as trends such as work-from-home, remote learning, and on-line shopping are key functional responses to pandemic infection risk. It may be that, long range, adaptation to the public health crisis will cause some permanent residual shifts in the way Americans live, work, learn, and shop. The greater the length of the pandemic itself, the more likely such changes are likely to be imprinted on the economy as a whole.17

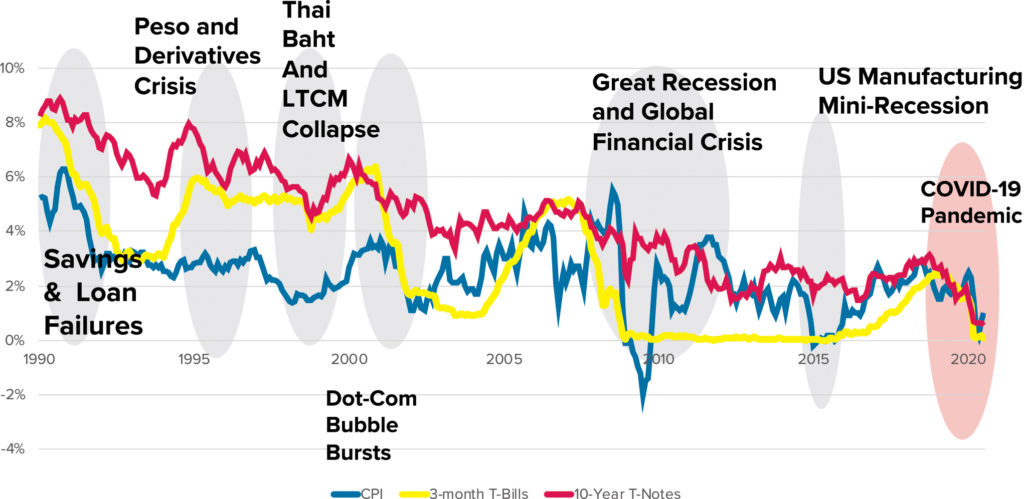

No doubt the improvement in stock prices is, in part, a result of the quick and decisive move by the Federal Reserve to drop interest rates once again toward the ‘zero bound.’ This is the seventh time in thirty years that the U.S central bank has had to intervene in a crisis. The Fed is becoming more expert and creative in applying its tools in times of trouble. It also means that it has learned that remedies must not only be supplied, but also sustained. (See the chart, “Thirty Years of Crisis Management at the Fed.”)

Thirty Years of Crisis Management at the Fed

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics (CPI); Federal Reserve (Interest Rates); Hugh Kelly Real Estate Economics (Event Characterization)

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has expressed the determination to do “whatever it takes” to assist the economy as the pandemic continues on. The response to the Great Recession demonstrates that once committing to dropping interest rates toward zero, the Fed is more than willing to hold them there until there is decisive evidence of economic improvement.18 One element in such willingness is the long-term evidence that the fear that monetary accommodation will lead inexorably to inflation has proven false over recent decades.

The consequence right now is that we can reasonably anticipate a period of low-cost capital until the economy has gotten back on its feet. By the measure of a return of GDP to 2019 levels, that will likely take until 2022, according to the consensus forecast of the Blue Chip Economists survey (as of August 10, 2020).

And even if the nation avoids slipping into a double-dip downturn (a “W” recession)19, the Congressional Budget Office projects that it will take until mid-2025 before employment gains take up the existing slack in the labor market, much less show the net increases we might have expected prior to the pandemic.20

Technology Seen as a Bright Spot for Many Local Economies

As the NASDAQ performance suggests, the unevenness of the 2020 economic adjustment does have hopeful elements amid the torrent of troubling news. Technology is one of those brighter spots. Shelter-in-place protocols have been a boon to firms providing a bridge for a population coping with the suddenly obligatory regimen of social distancing. In addition to strengthening the “virtual world”, the tech firms are impacting IRL (the world “in real life”). Amazon, for instance, reports that it has hired 175,000 fulfillment workers to cope with surging demand for deliveries. Facebook, in early August, announced a 730,000 sq. ft. office lease in New York City, meaning that all five “FAANG” tech giants (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google) have expanded this year in Manhattan or Brooklyn.21

It is not merely a New York story. As seen in the “Tech Hubs” table, employment services specializing in the tech sector identify a disparate set of metro areas attractive for tech workers, a growth sector of the labor market during a time of job contraction. Those cities are, generally speaking, those identified by research as 24-hour or 18-hour cities, or more descriptively as vibrant urban centers.22

Technology Hub Metros

|

Best Cities for Tech Jobs |

Emerging Tech Cities |

|

|

Atlanta |

Austin |

Baltimore |

|

San Francisco |

New York City |

Detroit |

|

San Diego |

Boston |

Houston |

|

Portland |

Seattle |

Miami |

|

Los Angeles |

Chicago |

Philadelphia |

|

Denver |

Dallas |

Phoenix |

Source: Career Karma

In the first weeks of the pandemic, there was much discussion about how the impact of COVID-19 would disadvantage such cities, due to density characteristics including high-rise buildings, public transportation, and clustering of high-occupancy entertainment venues. Two things have mitigated such assumptions as the months have passed. First, we are seeing evidence from around the world that mass transit systems such as those found in Paris, Milan, Hong Kong, and Tokyo do not exacerbate Coronavirus contagion, if riders and system employees take appropriate precautions.23 And, secondly, in the United States we are seeing that automobile-based metro areas and even low-density rural counties are just as susceptible to viral outbreaks as dense city centers.24 Leaping to conclusions is human nature, but no substitute for strategic thinking.25

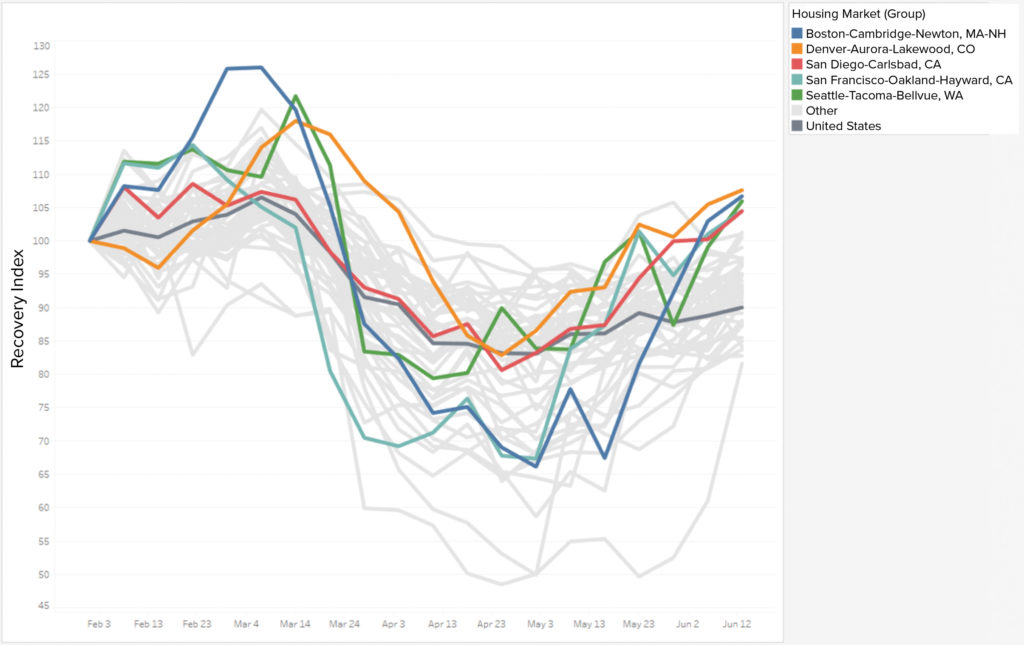

Initial Evidence from Housing: Economic Structure Rather than Metropolitan Geography Key to Location Choice

Source: Realtor.com

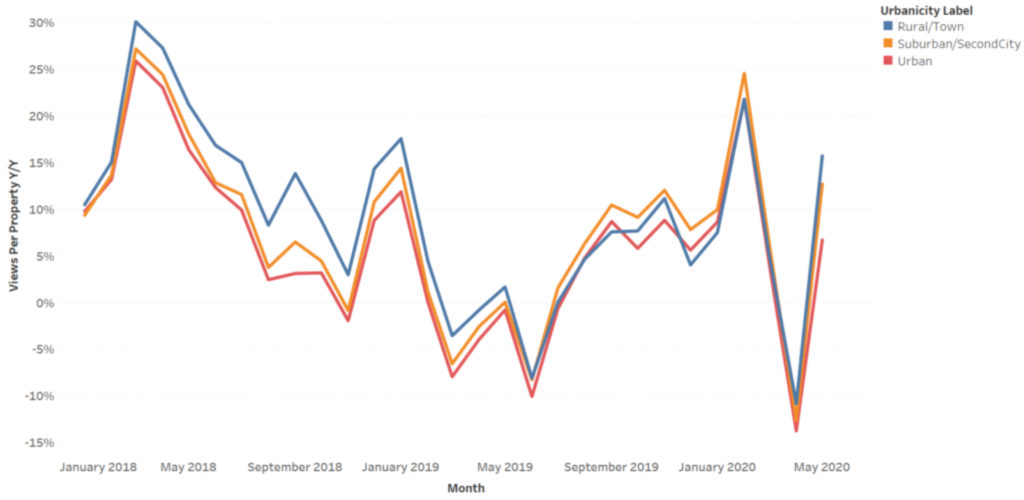

A final word on the “tech metros”: we should not be thinking of the central business districts alone as where benefit appears. The concept of the Metropolitan Statistical Area, as originally developed, saw a metro area as being a mutually interactive network of a core area and its associated suburbs. That is still a useful definition to keep in mind. As far as city/suburb/rural residential demand is concerned, NAR’s research department indicates some surprising strength on the housing front, with some marginal advantage to suburbs at the moment but with expectations that the major geographic categories will track in harmony in the coming year or so. REALTOR.com data shows remarkable consonance in urban core/suburban/rural and town homebuyer traffic both before and during the pandemic,26 and an indication that tech hubs including Boston, Denver, San Diego, San Francisco, and Seattle are ahead of the curve in a housing recovery.27

COVID-era Homebuying Traffic: Differences in Degree, but Similarity in Pattern

Source: Realtor.com

Managing the Disruption with both Schumpeter and Marshall

Virtually every economic forecast issued in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis bears the caution, “Current projections are subject to an unusually high degree of uncertainty.” The course of the pandemic, the efficacy and coordination of monetary and fiscal policy, the response of the financial markets, and the frictions stemming from a U.S. presidential election season: all make for exceptional caution on the part of forecasters.

Thus it seems best to outline a few possible (but not guaranteed) courses of action that have some demonstrable successes during an era of disruption.

From a Schumpeterian perspective, what can be creative in the midst of this discontinuous change in the economy? There are the lessons alluded to from the leadership of the Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower administrations.28

Franklin D. Roosevelt, faced with unemployment above 20 percent and a crisis of private capital, turned to the slack in the labor market and converted joblessness into a pool of human resources that could be put to productive use. If indeed there are some millions of jobs that have evaporated and are unlikely to return to private employment for several years, does it not make sense to find useful work to be paid for by the government? As it is, hundreds of billions of dollars are being committed just to provide households with some spendable income. Roosevelt funded lasting improvements to the nation’s environment through the Civilian Conservation Corps, enhanced America’s cultural heritage in music and the arts through the Works Progress Administration, and deployed workers with financial expertise to reform and restructure the banking system, in the process establishing oversight agencies such as the Securities Exchange Commission, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Social Security Administration. Such programs not only reduced unemployment in the short term, but had positive generational effects for the nation as a whole.

Harry S. Truman, faced with a potential depression when troops serving during World War II demobilized, instead crafted the GI Bill of Rights. This legislation encouraged soldiers to enroll in colleges and universities to gain the skills necessary for a restructured post-war economy. This was less a program of cash support than it was an investment in human capital. A similar need for educational investment exists today, especially as the U.S. winds down the post-9/11 wars that have vastly expanded the Defense budget. During the pandemic, the Army Corps of Engineers (for instance) was widely praised for its ability to augment medical facilities in Coronavirus hot spots. Training our military – in active service and on reserve – to place their skills to work in the civilian world – so that over the course of a working career they might bring key engineering, emergency medicine, logistics, and organizational talents to the economy – would be a contemporary application of the same principles.

Dwight D. Eisenhower looked at the sorry state of 1950s U.S. infrastructure and led the nation to create its Interstate Highway System. He also encouraged investment in science that paved the way for America’s space program that progressed swiftly from unmanned satellites, to the 1960s era Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo astronaut missions. Right now, the nation’s infrastructure deficiencies amount to $4.5 trillion of needed investment, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers.29 Federally funded Research and Development, meanwhile, has fallen from 1.8 percent of GDP at its peak in 1963, to just 0.6 percent in recent years.30 Both our aging infrastructure and our pullback on scientific funding go a long way to accounting for America’s pallid record in productivity gains over the past few decades.

Instead of dwelling on the “destruction” element of the situation, a Schumpeterian approach would look to such past successful programs as an indicator for creative, transformative economic interventions. From a funding perspective, there could be no better time than 2020, when the Federal government can issue 30 year bonds at an interest rate below 1.4 percent. It would be difficult NOT to achieve an attractive overall rate of return leveraging such a low cost of public debt.

At the same time, a refocusing on America’s cities would be a key step in adopting a sound Marshallian economic approach. This is incremental, since the economic ascendance of cities has been a consistent trend in U.S. history. As it is, the top ten metros account for 32 percent of total U.S. GDP.31 It makes good sense to build from this strong foundation.

The dynamic that accounts for this metropolitan dominance is another important concept identified by Marshall, namely, agglomeration. The interactions that are promoted by bringing industries and labor markets into proximity have been – and should continue to be – particularly fertile in stimulating innovation, the essential ingredient in re-establishing economic growth in an uncertain future. The contrary impetus to spreading out activity to smaller places not only dilutes the benefit of agglomeration but hinders the return of social vitality. And, as the evidence of the past several months shows, it does not effectively mitigate the spread of the Coronavirus into places of lower density.

Shifting focus toward essentials is another instance where there is ample opportunity for incremental gains, also well delineated by Marshall, who wrote in Principles, “It is common to distinguish necessaries, comforts, and luxuries; the first class includes all things required to meet wants that must be satisfied, while the latter consist of things that meet wants of a less urgent character.”32

The burdens of the pandemic have fallen disproportionately on America’s lower-income workers, the blue-collar sector, those without college degrees, women, and even healthcare workers. These are the members of the economy, of society itself, that are most at risk of food insecurity, housing displacement, reduced access to medical care as employment-based health insurance lapses, and difficulty in re-entering the ranks of the employed as businesses shut their doors.33

A Marshallian economics would prioritize attention and action on ‘the necessaries’ rather than ‘wants of a less urgent character.’ Hewing to such priorities would, not incidentally, bolster renewed effective demand for both residential and commercial real estate.

These are not at odds with the Schumpeterian steps suggested earlier. A program of public works (including but not restricted to infrastructure), funding for R&D advancing the technological frontier, using military training to address the nation’s skills gap, and expanding the educational support needed to gain access to growth industries are all incremental steps in service of the ‘creative’ side of creative destruction. They echo one of Marshall’s core arguments for capital investment: “The most valuable of all capital is that invested in human being.”34 •

Do you disagree with the author’s conclusion? Have a different opinion or point of view? Please share your thoughts with REI, or better yet prepare and submit a manuscript for publication by emailing the Real Estate Issues Executive Editor (or Board) on this article to rei@cre.org.

Endnotes

1. Clayton Christensen, The Innovators Dilemma, Harvard Business Review Press, (Cambridge, MA, 1997). ↩

2. Joseph Schumpter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, Harper & Bros., (New York, 1942) ↩

3. Often attributed to Maximilien Robespierre, but of uncertain specific provenance. Since the late 18th century it has been attributed to Napoleon, the French general Aimable Pelissier, Lenin, and Stalin. Cited as a proverb in The Hippie Dictionary: A Cultural Encyclopedia (and Phrasecon) of the 1960s, Joan Jeffers McCleary (ed), Random House (New York, 2004) p. 578. ↩

4. See W. Edwards Deming, Quality, Productivity, and Competitive Position, MIT Press (Cambridge, MA, 1982) ↩

5. Albert the Great (Albertus Magnus) is notable in his attention to the empirical world (plants, animals, astronomy, etc.) in an era where philosophers were more abstract. (Not much has changed there, after all!). Frederick Copleston in his History of Philosophy, vol. 2, part 2: Medieval Philosophy [Doubleday, New York 1948] remarks on Albert’s “spirit of curiosity and reliance on observation and experiment” (p. 130). Those characteristics were amply abundant in the work of Linnaeus, who developed the discipline of taxonomy [the scientific grouping or classification of organisms]. Social scientists, including economists, use the approach of organizing, categorizing, and ranking human systems as a discipline giving structure to their studies. Marshall, in Principles, [Macmillan, London, 1890] applies organization as an element in the analysis of capital, saying, “Capital consists in a great part of knowledge and organization: and of this some part is private property and other part is not. Knowledge is our most powerful engine of production; it enables us to subdue Nature and force her to satisfy our wants.” (p. 84) ↩

6. See this discussed in Hugh F. Kelly, 24-Hour Cities: Real Investment Performance, Not Just Promises. [Routledge, New York, 2016]. For an early consideration of the topic, see the author’s “Changes of State,” Real Estate Issues, Summer 1998, Vol. 23, No. 2. ↩

7. One characteristic of continuous change is that it can be modeled with fairly simple mathematics. Although large scale economic models are complicated engines with multiple variables, the basic pattern comes down to the sine curve (y= a sin [bx + c]), the general pattern of cyclical change. Trends can be graphed as a slope, (y=mx+b). Maturation typically follows the form of the logistics, or Sigma, curve and while its equation looks a little more complicated, it is still fairly simple and brief in form (dPdt=rP(1−PK). All three forms of continuous change are familiar in macroeconomics. Economic research into discontinuous change, however, has tended to focus on microeconomics – the behavior of firms – and the management study of transformational leadership. A good introduction may be found in David A. Nadler, Robert B. Shaw, A. Elise Walton, et al., Discontinuous Change: Leading Organizational Transformation, [Jossey-Bass Publishers, San Francisco, 1994]. ↩

8. There is a vast literature, including textbooks and historical studies, looking at the phases of the business cycle, for example, Lloyd M. Valentine and Carl A. Dauten, Business Cycles and Forecasting (6th ed.), [South-Western Publishing, Cincinnati OH, 1983].

For a brief and readable commentary of recent vintage, see Denzell Melles, “Economic Cycles and Why Self-Correction is A Good Thing,” March 19, 2019, accessed at https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/economic-cycles-why-self-correction-good-thing-denzell-melles/. Ray Dalio, of Bridgewater Associates, presents the fundamentals in a 30 minute video available at https://www.bridgewater.com/how-the-economic-machine-works. ↩

9. See Greenspan, art. cit., pp. 88 – 96. The former Federal Reserve Chairman, widely dubbed the ‘maestro’ prior to the Global Financial Crisis, says this in the article, an apologia for bankers in the meltdown of 2007 – 2010: “The financial crisis that ensued represented an existential crisis for economic forecasting. The conventional method of predicting macroeconomic developments-econometric modeling, the roots of which lie in the work of John Maynard Keynes-had failed when it was needed most, much to the chagrin of economists. In the run-up to the crisis, the Federal Reserve Board’s sophisticated forecasting system did not foresee the major risks to the global economy.” Greenspan’s proposed remedy, however, is to tweak those very same models by incorporating some other insights of Keynes, particularly the recognition of ‘animal spirits’ (psychological reactions that induce ‘irrational’ behaviors in the marketplace, and more modern contributions of behavioral economists such as Daniel Kahneman relating to asymmetrical preferences leading to risk aversion. Such tweaking, however, does little to anticipate the kinds of market failure that have recurred historically. See John Kenneth Galbraith, A Short History of Financial Euphoria [Penguin Books, New York, 1990} and Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable [Random House, New York, 2007]. ↩

10. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed through https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet ↩

11. Employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics are the latest available as of September 7, 2020 and were accessed at https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm. ↩

12. U.S., Department of Labor, News Release, September 3, 2020. ↩

13. To monitor industry-by-industry details, see the monthly release of the “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This essay reviewed the release of August 10, 2020. ↩

14. U.S. Chamber of Commerce and US Small Business Administration data cited in Madeleine Ngo, “Small Businesses Are Dying by the Thousands — And No One Is Tracking the Carnage,” Bloomberg News, August 11, 2020; accessed through, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/on-small-business/small-businesses-are-dying-by-the-thousands–and-no-one-is-tracking-the-carnage/2020/08/11/660f9f52-dbda-11ea-b4f1-25b762cdbbf4_story.html. ↩

15. Equities market data, year to date, as of August 24, 2020. ↩

16. On August 24, 2020, Salesforce, Amgen and Honeywell were added to the Dow, replacing Exxon-Mobil, Pfizer and Raytheon Technologies Over time, the “industrial” character of the DJIA has become less reflective of traditional “heavy” industries. The Dow 30 now includes companies such as Visa, Goldman Sachs, Walmart, and Walt Disney.↩

17. Note, for example, how post-9/11 adjustments including airport screenings, identity checks on entering office buildings, and security procedures for package delivery to businesses tightened as a response to the experience of terrorism and have remained in place now for nearly two decades. ↩

18. The June 2020 Monetary Policy Report of the Federal Reserve says, “With regard to [Federal Reserve Open Markets Committee] participants’ projections of appropriate monetary policy, almost all participants expected to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent through at least the end of 2022.” ↩

19. That survey places 4Q2019 real GDP at $19,254.0 billion, and 4Q2021 real GDP at $19,066.3 billion. ↩

20. The CBO’s most recent ten-year projections show 4Q2019 non-farm employment at 151.8 million, and recovery to this level occurring in 3Q2025. Projections accessed at https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data#4. By contrast, the CBO’s pre-pandemic projection had non-farm employment at 155.3 million for 3Q2025, indicating that the COVID-19 impact on employment for the first half of the 2020s is roughly 3.5 million jobs. That is the slack that could be addressed by policy measures suggested at the conclusion of this essay. ↩

21. See https://ny.curbed.com/maps/amazon-google-facebook-nyc-offices for details. ↩

22. Analyses of such metro areas can be found in Hugh F. Kelly, Alastair Adair, Stanley McGreal, and Stephen Roulac, “Twenty-four Hour Cities and Commercial Office Building Performance” Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management: 2013, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 103-120. Also, Hugh F. Kelly and Emil Malizia, “Defining 24-Hour and 18-Hour Cities, Assessing Their Vibrancy, and Evaluating Their Property Performance” Journal of Real Estate Portfolio Management: 2017, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 87-103. ↩

23. See https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/08/28/907106441/coronavirus-faq-is-it-safe-to-get-on-the-bus-or-subway (August 28, 2020); an earlier article in The Atlantic examined the alarm about mass transit and dense cities, but indicated that in Europe and Asia evidence indicated that reliance on mass transit did not correlate with Coronavirus outbreaks

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/fear-transit-bad-cities/612979/ ↩

24. As we gain more experience with the Coronavirus, it appears that risks of contagion are more tied to behaviors than to places. Events where unsafe practices have led to notable spread have included outdoor recreation, political rallies, student parties at re-opening schools, and even religious services. ↩

25. As I have written elsewhere: Hugh F. Kelly, “Look Before You Leap,” Commercial Property Executive (September 2020), accessible at https://www.cpexecutive.com/post/economists-view-look-before-you-leap/ ↩

26. Nicolas Beco, Realtor.com Economic Analyst, June 17, 2020, “Housing Market Rankings in Suburban Communities Outpaced Urban Areas in May.” Accessed at https://www.realtor.com/research/housing-market-rankings-in-suburban-communities-outpaced-urban-areas-in-may/ ↩

27. See discussion in https://www.realtor.com/research/housing-market-recovery-index-trends-june-13-data/ ↩

28. Although I look back at these historical examples, I regard adoption in the COVID-19 era to be discontinuous (and therefore Schumpeterian), since my suggested policy moves are more than just an outgrowth of existing government programming. Indeed, returning to the approach of Presidents Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower reverses Federal trends in place for roughly the past 40 years. ↩

29. See ASCE’s website and the historical trends in its report card on the nation’s infrastructure at https://www.infrastructurereportcard.org/making-the-grade/report-card-history/

30. National Science Board, “Research and Development: US trends and international comparisons,” [NSB 2020-3, January 15, 2020], p. 18. ↩

31. Gross metro product is available at https://www.bea.gov/data/gdp/gdp-county-metro-and-other-areas ↩

32. Op. cit., p. 47. ↩

33. See, among many published analyses, this discussion from the Urban Institute: https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/covid-19-crisis-continues-have-uneven-economic-impact-race-and-ethnicity↩

34. Op cit., p. 324. ↩

Photo: zimmytws/Shutterstock.com

Photo: zimmytws/Shutterstock.com