A Collaborative Approach for a Complex Valuation Engagement and Its Daubert Compliance with Generally Accepted Authorities

Accurate valuations of complex assets require a cooperative multidisciplinary approach. Users of appraisals would be best served if business valuers, personal property appraisers, and real property appraisers collaborated on complex assignments, rather than solving for a residual value outside the appraiser’s individual technical skillset. This notion was successfully tested in a recent precedent-setting trial in Florida.

On June 16, 2016, Walt Disney Parks and Resorts US, Inc., a Florida corporation, sued Defendant, Rick Singh of Orange County as Property Appraiser among others (the Disney matter) and alleged among other things that the Defendant estimated the just and assessed value of the Subject Property (the Disney Yacht and Beach Club Resort as of January 1, 2015) for ad valorem purposes as $336,922,772 (Just Value)1 and $169,652,408 (Assessed Value).2 The Complaint continues that the Property Appraiser included the value of certain intangible property in the assessments, in violation of article VII, section 1(a) of the Florida Constitution.3 The effect of this new assessment was to double the Walt Disney Parks and Resorts US, Inc., (Disney) property taxes for 2015. This specific increase was approximately $2 million additional tax liability for the 2015 tax year. Given that Disney has four years’ exposure (2015 – 2018) and eleven similar hotels, however, the accumulated impact to date would approximate $88 million. Disney prevailed in a Final Judgment for Plaintiff ordered by Judge Thomas W. Turner filed July 3, 2018.4

Joint experts5 were hired by Disney to allocate asset and income streams to tangible and intangible properties. The purpose of this article is to present some of the financial tools and methods used by the joint experts in the Disney matter, in compliance with Federal law, that implicitly requires professional cooperation among real property, personal property, and business appraisers. Each of these disciplines now requires collaborative support of value opinions for enterprises that include combinations of real, personal, and intangible property. Thus, decades of technical argument can be resolved through disciplinary convergence and the broader perspective it renders.

Daubert Compliance

Maintaining independence and objectivity throughout the implicit and explicit convergence of real property, personal property, and business appraisers, and the ethical responsibilities each expert had in assessing the other’s specialty expertise while maintaining individual testimony in agreement with Daubert compliance was challenging. The Frye standard6 has now been modified by the Daubert standard in Florida.7 While many interpret 1993 Daubert as providing a checklist to guide the Court as gatekeeper, the original Supreme Court Daubert decision actually opines “[t]he Federal Rules of Evidence, not Frye, provide the standard for admitting expert scientific testimony in a federal trial.”8 Of course, the Disney matter was not held in Federal court. However, due to the likely high profile, the joint experts wanted to satisfy the highest standard for experts. From Daubert and subsequent cases comes a list, perhaps best presented by the Eleventh Circuit, establishing that admissible expert testimony must meet three requirements:9

- The expert is qualified to testify competently regarding the matters he intends to address;

- The methodology by which the expert reaches his conclusions is sufficiently reliable, as determined by the sort of inquiry mandated by Daubert; and

- The testimony assists the trier of fact, through the application of scientific, technical, or specialized expertise, to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue.

In a nutshell, a judge considering a Daubert motion must determine:

- Does the expert’s methodology satisfy the scientific method?

- Is the expert qualified in a manner that is relevant to the facts of the matter and will aid the court?

- Is the expert’s methodology reliable and broadly accepted?

- Can the expert’s hypothesis and conclusions be tested independently, objectively, and empirically?

Financial experts use particular methods not commonly known to non-financial courts, thus creating a communication gap. Understanding and observing the methods at both quantitative and qualitative levels of judgment above the threshold of materiality evidenced by broadly applied checklists traced ultimately to peer reviewed generally accepted methodology will go a long way to bridging that communication gap. The joint experts left a clear trail of documentation in the work papers and checklists to demonstrate compliance with the Daubert Test, namely:

- Peer reviewed methodology,

- Error rate established,

- Tested empirically,

- Accepted generally in the expert’s industry, and

- Litigation and non-litigation use of methodology is established.

Of course, the $88 million question was: How do the joint experts comply with all of this using two different professional specialties applied to tangible and intangible assets?

Collaborating Specialists

In today’s world of multi-disciplinary projects, understanding, and therefore embracing, the intersection of two disparate disciplines can be perplexing. It’s challenging for several reasons, not the least of which is that the real estate appraiser’s and the business appraiser’s jargon use the same words, but with different meanings and in different contexts. Regardless of whether the lead appraiser is the real estate, tangible personal, or business appraiser, the lead must now consider collaborating with a qualified (by virtue of skill, education, and experience) specialist counterpart. Certainly in the world of financial reporting, auditors must now consider working together with a knowledgeable real estate appraiser. Specifically10:

The market for valuation-related services in financial reporting is seen as a potential growth area for real estate valuers, working with (or for) accountants, business valuers, and personal property appraisers. As a significant example, corporate assets often must be valued for inclusion on corporate financial statements. A corporate merger or acquisition also triggers a valuation of the entire business, requiring that allocations be made for tangible and intangible assets in addition to determining if there is any residual goodwill in the business value….

In valuation for financial reporting assignments, a valuer may be recognized as what auditing standards consider a specialist. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants defines a specialist as “a person (or firm) possessing special skill or knowledge in a particular field other than accounting of auditing,” according to AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards No. 73: Using the Work of a Specialist. In this context, an appraiser has the valuation knowledge and expertise that auditors are neither required nor expected to have, such as specialized knowledge of professional valuation standards, relevant state laws and regulations, property characteristics and utility, trends in market conditions, and analysis of the highest and best use of real property. However, auditors generally are expected to be able to use the audit evidence provided by a valuation specialist.

Clearly, The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th Edition borrowed the requirements of determining a specialist from the AICPA, but how is this to be applied in assessing the specialty expertise of real property, personal property, and business appraisers? Specifically, how is a real property appraiser supposed to “test the chops” of a business appraiser? Conversely, how is a business appraiser expected to “test the chops” of a real property appraiser?

To be clear, the days of blindly relying on the other expert are over. An appraiser today cannot simply hire another appraiser and think one’s professional obligations are satisfied. We must be cognizant of and conversant with the other’s regulatory requirements, jargon, and theoretical positions. Importantly, this goes both ways. There are no more “black box” excuses for a lack of professional competence. You must be able to understand each other at a workable level and apply that knowledge to the assignment in the real time development of that assignment. Bridging this gap begins with understanding regulatory expectations.

In 2003, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) released its Commission Statement of Policy Reaffirming the Status of the Financial Accounting Standards Board as a Designated Private-Sector Standard Setter11 that states:

The Securities and Exchange Commission has determined that the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB or Board) and its parent organization, the Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF), satisfy the criteria in section 108 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and, accordingly, FASB’s financial accounting and reporting standards are recognized as “generally accepted” for purposes of the federal securities laws. As a result, registrants are required to continue to comply with those standards in preparing financial statements filed with the Commission, unless the Commission directs otherwise.

Federal law through the SEC, as well as FIRREA, requires professional cooperation among real property, personal property, and business appraisers. None of these disciplines can independently credibly support value opinions for enterprises that include combinations of real, personal, and intangible property. Thus, decades of myopic technical argument can be resolved through interdisciplinary collaboration and the broader perspective it renders.

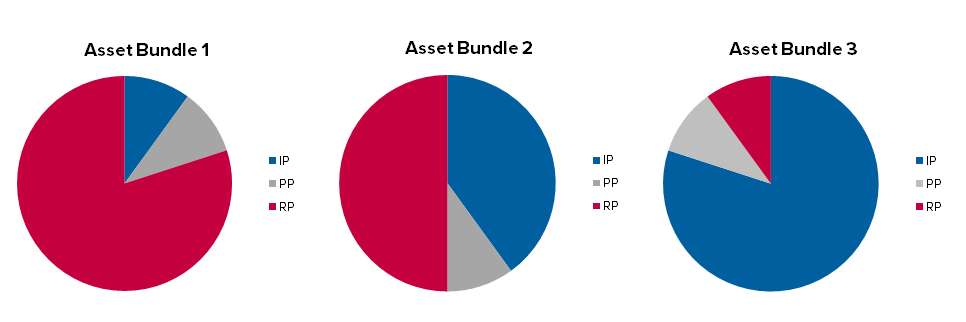

Many property types, requiring valuation for a variety of purposes, are actually bundles of underlying assets. See Figure 1. Asset bundles are commonly referred to as assets, properties, or businesses. Asset bundles comprising more than one class of property arguably requires cooperative teamwork between two or more competent valuation professionals if credible results are to be rendered.

Figure 1

Weighted Average Return on Assets (WARA)12

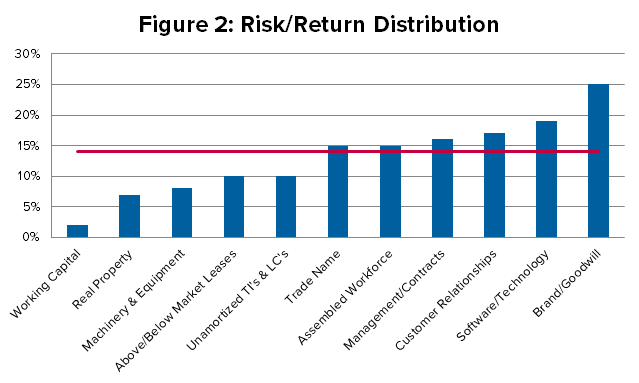

Figure 2 is presented for illustrative purposes and is not specific to the Disney matter due to certain information sealed by the Court. In the illustrative summary of values presented, the valuation conclusions are separated into the following groups: elements of net working capital, property, plant and equipment, intangible assets, and goodwill. Individual asset valuations are presented within each group (see Figure 2). The weighted average return on assets (WARA) helps visualize why accurate valuations of complex assets require a collaborative multidisciplinary approach.

In addition to presenting the summary of values, the WARA provides a sanity check in the form of a weighted return calculation. The WARA calculation employs the rate of return for each asset, weighted according to its value relative to the whole. The WARA should approximate the overall weighted average cost of capital for the business.

Multiperiod Excess Earnings Method (MPEEM)13

Major assets for which it is possible to isolate discrete income streams are often valued using the Income Approach-Multiperiod Excess Earnings Method (MPEEM). This is essentially a discounted cash flow method for each asset and honors the concept that the value of an asset, including identifiable intangible assets, is equal to the present value of the net cash flows attributable to that asset, and recognizes the notion that the net cash flows attributable to the subject asset must recognize the support of many other assets, tangible and intangible, which contribute to the realization of the cash flows.

The MPEEM measures the present value of the future earnings to be generated during the remaining lives of the subject assets. Using the enterprise (100%) value of the business (i.e. the Business Enterprise Value or BEV) as a starting point, pretax cash flows attributable to the acquired assets as of the valuation date are calculated. The discount rates shown at Figure 2 are for illustrative purposes only and represent general relationships among assets. Actual rates must be selected based on consideration of the facts and circumstances related to each category of asset as determined based on market participants. A fundamental tenet of economics holds that return requirements increase as risk increases, with many intangible assets being inherently more risky than tangible assets. It is reasonable to conclude that the returns expected on many intangible assets typically will be at or above the average rate of return (discount rate) for the company as a whole. Note the returns expected on intangible assets may be below the company average for a hotel business with a mix of tangible and intangible assets. The relationship of the amount of return, the rate of return (including risk), and the value of the assets creates a mathematical relationship as previously discussed.

The Contributory Asset Charge Guide Describes Returns On and Of

In applying the MPEEM to any asset, after-tax cash flows attributable to the asset are charged amounts representing a “return on” and, in some cases, a “return of” these contributory assets. The contributory asset charge (or CAC) is calculated based on the value of the contributory asset. Simply stated, it represents the value of a contributory asset multiplied by a required rate of return on, and in some cases of, that contributory asset. The return on the asset refers to a hypothetical assumption whereby the project pays the owner of the contributory assets a market return on the value of the hypothetically rented assets (in other words, return on is the payment for using the asset – an economic rent). For self-developed assets (e.g., assembled workforce or customer base), the annual cost to replace such assets should be factored into cash flow projections as part of the operating cost structure (e.g., sales and marketing expenses could serve as a proxy for a return of customer relationships). Similarly, the return of fixed assets can be included in the cost structure as depreciation, which effectively acts as a surrogate for a replacement charge.

Together returns on and of, or contributory charges, represent charges for the use of contributory assets employed to support the subject assets and help to generate revenue. The cash flows from the subject assets must support charges for replacement of assets employed, tangible or intangible, and provide a market return to the owners of capital. The respective rates of return are directly related to the analyst’s particular assessment of the risk inherent in each asset. Generally, it is presumed that the return of the asset (reflecting the “using up” of the asset) is reflected in the operating costs when applicable (e.g., depreciation expense). The contributory asset charge is the product of the tangible or intangible asset’s value and the required rate of return on that asset.

The distinguishing characteristic of a contributory asset is that it is not the subject income-generating asset itself. Rather it is an asset that is required to support the subject income-generating asset. The CAC represents the charge that is required to compensate for an investment in a contributory asset, giving consideration to rates of return required by market participants investing in such assets. Figure 3 provides examples of assets typically treated as contributory assets, and suggested bases for determining the market return.

Figure 3

| Asset | Basis of Charge |

| Working capital | Short-term lending rates for market participants (e.g., working capital lines or short-term revolver rates) |

| Fixed assets (e.g., property, plant, and equipment) | Financing rate for similar assets for market participants (e.g., terms offered by vendor financing), or rates implied by operating leases, capital leases, or both, typically segregated between returns of (i.e., recapture of investment) and returns on |

| Workforce (which is not recognized separately from goodwill), customer lists, trademarks, and trade names | Weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for young, single-product companies (may be lower than discount rate applicable to a particular project) |

| Patents | WACC for young, single-product companies (may be lower than discount rate applicable to a particular project). In cases where risk of realizing economic value of patent is close to or the same as risk of realizing a project, rates would be equivalent to that of the project. |

| Other intangibles, including base (or core) technology | Rates appropriate to the risk of the subject intangible. When market evidence is available, it should be used. In other cases, rates should be consistent with the relative risk of other assets in the analysis and should be higher for riskier assets. |

It is important to note that the assumed value of the contributory asset is not typically static over time. Working capital and tangible assets may fluctuate throughout the forecast period, and returns are typically taken on estimated average balances in each year. Average balances of tangible assets subject to accelerated depreciation may decline as the depreciation outstrips capital expenditures in the early years of the forecast. While the carrying value of amortizable intangible assets declines over time, there is a presumption that such assets are replenished each year, so the contributory charge usually takes the form of a fixed charge each year. An exception to this rule is a noncompete agreement, which is not replenished and does not function as a supporting asset past its expiration period.

Income, Rate, and Value Relationships

The income and return relationship to value applies to all asset classifications, whether tangible or intangible. The income and return relationship to value, when properly applied to an array of assets, will convey economically viable returns whose average weights sum to a viable weighted average cost of capital that reconciles with the band of investment. It is a fundamental axiom enshrined in The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th Edition14 that:

A $ return divided by a respective rate of return = value for the asset (I/R = V, or IRV)

If this is true, then:

A $ return divided by a respective rate of return = value for an intangible asset

Further:

A $ return divided by value = a respective rate of return

And:

A respective rate of return times value = $ return

While the readers of this article likely understand these relationships, it’s important for this article to clarify that, in the Disney matter, the Court also understood these relationships through the testimony of the fact and expert witnesses. The character of the asset being valued is irrelevant to this fundamental relationship. Of course, if the subject is comprised of multiple assets (e.g. cash, personal property, leasehold interests, real property, etc.), then each asset will have a separate and distinct return. For instance, the return on cash might be 2% in today’s environment. By operation, the weighted average of all of the property’s returns will equal the weighted average return for the property as a whole.

Absent a collaborative approach, heretofore, business and real estate appraisers have frequently relied on residual methodologies to address the unknowns outside their disciplinary expertise when valuing the various components comprising a business enterprise. This practice has only further exacerbated disagreement among professionals and inaccurate valuations.15

For example, business appraisers often value the various business components of an enterprise and “solve” for the real property value using a residual. It’s logical that the value of real property can be expressed as a component of the total value of the income producing property (i.e. its business enterprise value), less each of the component asset values of that enterprise. Likewise, real estate appraisers frequently “solve” for the residual business component. Rather than operating in a vacuum, collaborating with a specialist appraiser renders a more credible, defensible result. And, because the sum total of the returns weighted by value will equal the overall weighted average cost of capital for the business enterprise value, the reconciliation process becomes a sanity test for the overall valuation exercise.

The weighted average return on assets is mathematical and applies whether the premise is “value in use” or “value in exchange.” That is, when all assets, tangible and intangible, are properly segregated, the value premise for the real property should be consistent with the overall business valuation or appropriate legal premise.

Final Judgment for Plaintiff

The Court obviously recognized the interplay between assets, whether tangible or intangible, and income, holding16:

The Court holds that it is improper to consider the income from the business activities conducted on the property in establishing just value of the subject property….

Here, in using the income approach to value Disney’s real property, the Property Appraiser also had a duty to deduct the values of nontaxable items, specifically tangible and intangible assets “to ensure” that the income used is “solely attributable to” Disney’s real property…. But by simply concluding that the $74 million of income from food, beverage, and other items was “inextricably intertwined” with the real estate, the Property Appraiser breached that duty and unconstitutionally taxed value from Disney’s intangible property….

Essentially after hearing all testimony, the Court held that the $74 million was Ancillary Income applicable only to intangible assets. Therefore, the Court addressed this income stream using the Property Appraiser Expert’s inputs.17

Because there is competent, substantial evidence of value in the record that allows the Court to establish the assessment of Yacht and Beach Club, the Court will establish the assessment, using the figures submitted…. This Court notes that the net effect is that the calculations are not materially different under the parties’ calculations once the ancillary income figures are excluded, and the Court’s failure to consider Disney’s other claimed intangible assets is of no consequence in this case. The Court finds that the Property Appraiser’s use of the Rushmore method in this case failed to specifically exclude the ancillary income previously discussed….

Therefore, the revised just value for the Yacht and Beach Club for 2015 is $188,991,357.

Based on a petition for rehearing, the Court corrected a math error. The Court’s revised Just Value for the Yacht & Beach Club for the 2015 assessment year was $209,156,074, within eleven percent of Disney’s appraiser’s value. •

The authors thank Joryn Jenkins, Esq., for her review and suggestions to this article. The authors are responsible for all content.

Author Michael J. Mard, CPA/ABV, CPCU, gratefully acknowledges John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and its cooperation granting permission for some original work used as a basis for this article, especially from the author’s Valuation for Financial Reporting, 2002, 2007 and 2010. All work used with permission. This article represents original work by the authors.

Endnotes

1. Florida Department of State, Florida Administrative Code & Florida Administrative Register 12D-1.002 Definitions, Unless otherwise stated or unless otherwise clearly indicated by the context in which a particular term is used, all terms used in this chapter shall have the same meanings as are attributed to them in the current F.S. In this connection, reference is made to the definitions contained in Sections 192.001, 196.012, and 197.102, F.S., (2) “Just Value” – “Just Valuation”, “Actual Value” and “Value” – Means the price at which a property, if offered for sale in the open market, with a reasonable time for the seller to find a purchaser, would transfer for cash or its equivalent, under prevailing market conditions between parties who have knowledge of the uses to which the property may be put, both seeking to maximize their gains and neither being in a position to take advantage of the exigencies of the other. ↩

2. Complaint filing #42883479, IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE NINTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT IN AND FOR ORANGE COUNTY, FLORIDA, CIVIL DIVISION, Case No.: 2016-CA-005297-0, WALT DISNEY PARKS AND RESORTS US, INC., a Florida corporation, Plaintiff, vs. RICK SINGH, as Property Appraiser; SCOTT RANDOLPH, as Tax Collector; REEDY CREEK IMPROVEMENT DISTRICT, a political subdivision of the State of Florida, and LEON BIEGALSKI as Executive Director of the Florida Department of Revenue, Defendants. ↩

3. Ibid, paragraph 14. ↩

4. Final Judgment for Plaintiff, Filing # 74427259 E-Filed 07/03/2018 10:34:41 AM ↩

5. Full Disclosure: The authors were retained by the Plaintiff as joint experts in the Disney matter. Further, because some of the evidence was sealed, this article honors that confidentiality and fully uses illustrative examples unrelated to the Plaintiff but which sufficiently describe the process. ↩

6. This standard comes from Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923), a case discussing the admissibility of polygraph test as evidence. The Court in Frye held that expert testimony must be based on scientific methods that are sufficiently established and accepted. The court opined:

Just when a scientific principle or discovery crosses the line between the experimental and demonstrable stages is difficult to define. Somewhere in this twilight zone the evidential force of the principle must be recognized, and while the courts will go a long way in admitting experimental testimony deduced from a well-recognized scientific principle or discovery, the thing from which the deduction is made must be sufficiently established to have gained general acceptance in the particular field in which it belongs.

7. Section 1. Section 90.702, Florida Statutes, was amended in 2013 to read:

90.702 Testimony by experts.—

(1) If scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will assist the trier of fact in understanding the evidence or in determining a fact in issue, a witness qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education may testify about it in the form of an opinion or otherwise, if:

(a) The testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data;

(b) The testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

(c) The witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.

↩

8. Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).↩

9. Rink v. Cheminova, Inc., 400 F.3d 1286, 1291-92 (11th Cir. 2005) (quoting City of Tuscaloosa v. Harcros Chems., Inc., 158 F.3d 548, 562 (11th Cir. 1998)); e.g., Madura v. BAC Home Loans Servicing L.P., 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 103639, 2013 WL 3777094 (M.D. Fla. July 17, 2013). The proponent of the expert witness must establish each of these elements by a preponderance of the evidence. Rink, 400 F.3d at 1292; Allison v. McGhan Med. Corp., 184 F.3d 1300, 1306 (11th Cir. 1999). ↩

10. Op. Cit. The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th Ed. p. 695-696 ↩

11. Release Nos. 33-8221; 34-47743; IC-26028; FR-70; https://www.sec.gov/rules/policy/33-8221.htm ↩

12. Mard, Michael J., Hitchner, James R., Hyden, Steven D., Valuation for Financial Reporting, Fair Value, Business Combinations, Intangible Assets, Goodwill, and Impairment Analysis, Third Edition, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011. Page 46. Print. ↩

13. Financial Accounting Standards Board, Accounting Standards Codification 820-10-55-3 d. [An asset’s use in combination with other assets or with other assets and liabilities might be incorporated into the valuation technique used to measure the fair value of the asset. That might be the case when using the multiperiod excess earnings method to measure the fair value of an intangible asset because that valuation technique specifically takes into account the contribution of any complementary assets and the associated liabilities in the group in which such an intangible asset would be used. [FAS 157, paragraph A5, sequence 123]] ↩

14. The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th Edition, © 2013, Appraisal Institute • 200 W. Madison • Suite 1500 • Chicago, IL 60606 • www.appraisalinstitute.org, page 492, Chapters 23, 24, et al. ↩

15. A Business Value Enterprise Anthology, Appraisal Institute © 2001 and 2011 ↩

16. Final Judgment for Plaintiff, Op. Cit. pages 13, 14. Citations omitted. ↩

17. Ibid, pages 17 – 20 ↩

Photo: James Kirkikis/Shutterstock.com

Photo: James Kirkikis/Shutterstock.com