Introduction

In the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession, cities globally faced a pivotal moment, urgently seeking rejuvenation and renewal amidst economic turmoil. Urban planners and policymakers embarked on a quest for innovative solutions to breathe new life into struggling urban landscapes. It is within this context that the concept of innovation districts emerged as a beacon of hope for economic recovery, championing creativity, entrepreneurship, and collaborative knowledge-sharing. This article aims to dissect the phenomenon of innovation districts, uncovering the key elements essential for their success.

Defining Innovation Districts

The concept of innovation districts represents a response to the economic challenges post-2008, providing focal points for knowledge-based development within urban landscapes. These districts foster collaboration between public and private entities to nurture, attract, and retain investments and talent. Within these dynamic environments, a diverse creative class comprising knowledge workers, entrepreneurs, startups, and business incubators converges, synergistically contributing to urban revitalization and the advancement of knowledge-driven economic activities. Leveraging the density and clustering of institutions and companies, innovation districts promote knowledge sharing, collaboration, and the acceleration of innovation, productivity, and creativity.

The Crucial Role of Innovation Districts

The significance of innovation districts lies in their remarkable ability to tackle the challenges faced by metropolitan areas in the post-recession era, offering viable solutions to job scarcity, poverty, and fiscal constraints. These districts act as catalysts for job creation by fostering collaboration across diverse sectors, empowering entrepreneurs with accessible resources, and promoting social equity by revitalizing disadvantaged neighborhoods and providing avenues for skill development. Furthermore, innovation districts play a pivotal role in promoting environmental sustainability by encouraging denser development and mitigating carbon emissions, all while generating revenue for municipal governments to invest in critical infrastructure and services.

Innovation districts often become focal points for real estate investment and development, triggering increased demand for properties in the area. The influx of businesses, startups, and research institutions contributes to rising property values due to the desirability of being situated near these innovation hubs. These districts typically feature a mix of residential, commercial, and recreational spaces, creating a vibrant live-work-play environment that attracts various stakeholders. This surge in demand for mixed-use developments can drive up property prices and rental rates, particularly for properties located within or near the district. However, alongside the opportunities brought by innovative districts, concerns about gentrification and exclusivity arise, limiting access to benefits solely to district residents. This situation can lead to socio-economic disparities in income, social status, and racial polarization. To address these potential impacts, both local governments and developers have implemented strategies to mitigate negative externalities. Initiatives such as inclusive entrepreneurship programs and communities for underrepresented groups aim to tackle issues of exclusion, ensuring that innovation districts have an inclusive socio-economic impact throughout the region, benefiting a diverse range of communities.

The Diverse Models of Innovation Districts

The Brookings Institution’s study (2018) outlined three general innovation district models that provide a nuanced understanding of their dynamics and impact.

- Anchor Plus: The “anchor plus” model, primarily found in the downtowns and mid-towns of central cities, centers around large-scale mixed-use development anchored by major institutions and a rich ecosystem of related firms, entrepreneurs, and spin-off companies engaged in commercializing innovation. Kendall Square in Cambridge and the Cortex district in St. Louis exemplify this model.

- Re-Imagined Urban Areas: The “re-imagined urban areas” model, often located near historic waterfronts, represents a transformation of industrial or warehouse districts into vibrant hubs fueled by transit access, historic building stock, and proximity to downtowns in high-rent cities. This model is showcased in the revitalization efforts of Boston’s South Boston waterfront and Seattle’s South Lake Union area.

- Urbanized Science Parks: Commonly found in suburban and exurban areas, the “urbanized science park” model involves the urbanization of traditionally isolated innovation areas through increased density and diverse activities like retail and restaurants. North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park stands as a prime example of this model’s success.

Idris conducted research on the impact of innovation districts in 2022 by analyzing the index for total employment and other demographic data. Regardless of the type—whether anchor plus, re-imagined urban areas, or urbanized science park—the presence of an innovation district improves the economy of the area.

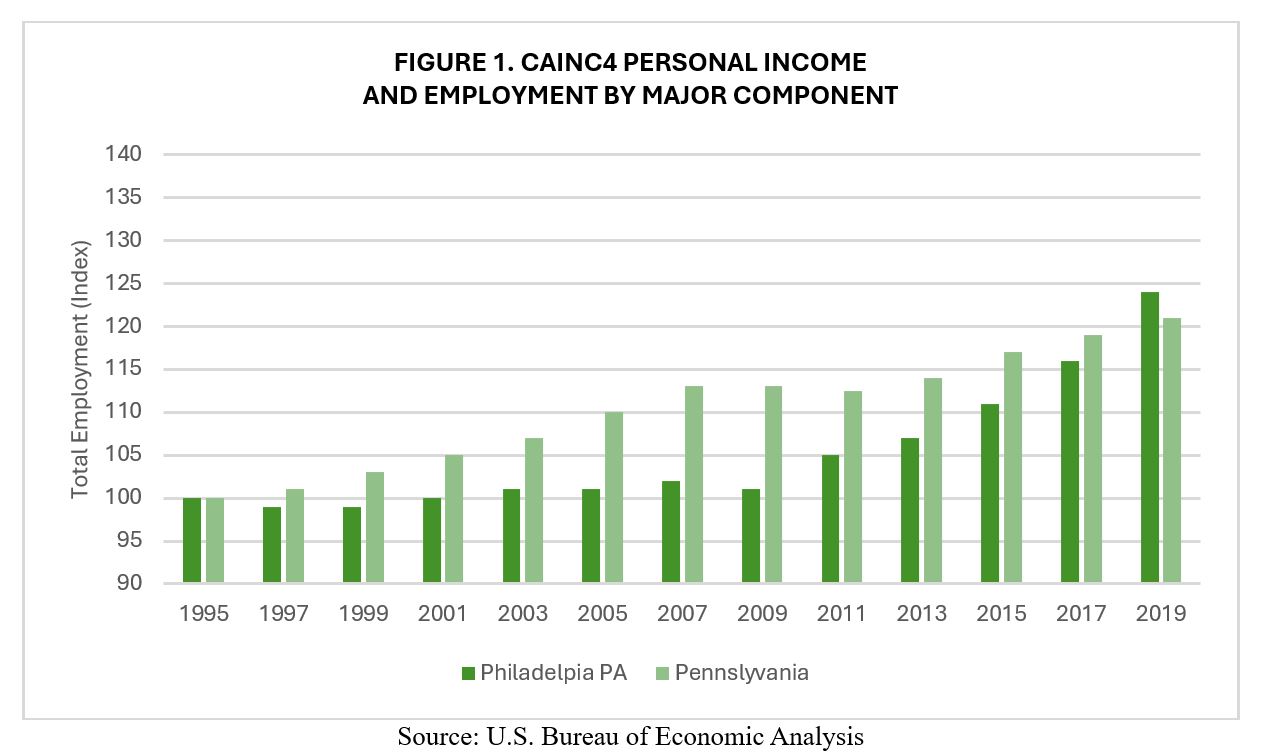

In the research, the anchor plus model was exemplified by Philadelphia’s University City, located in Pennsylvania County. The University City District (UCD) played a pivotal role in revitalizing Philadelphia’s urban landscape starting in 1995. To demonstrate the impact of this district, the total employment index was analyzed in Figure 1 below, which reveals a consistent outperformance of Pennsylvania County compared to Philadelphia State in terms of the total employment index from 1995 to 2019. This trend can be linked to the district’s transformation, attracting a significant influx of private firms.

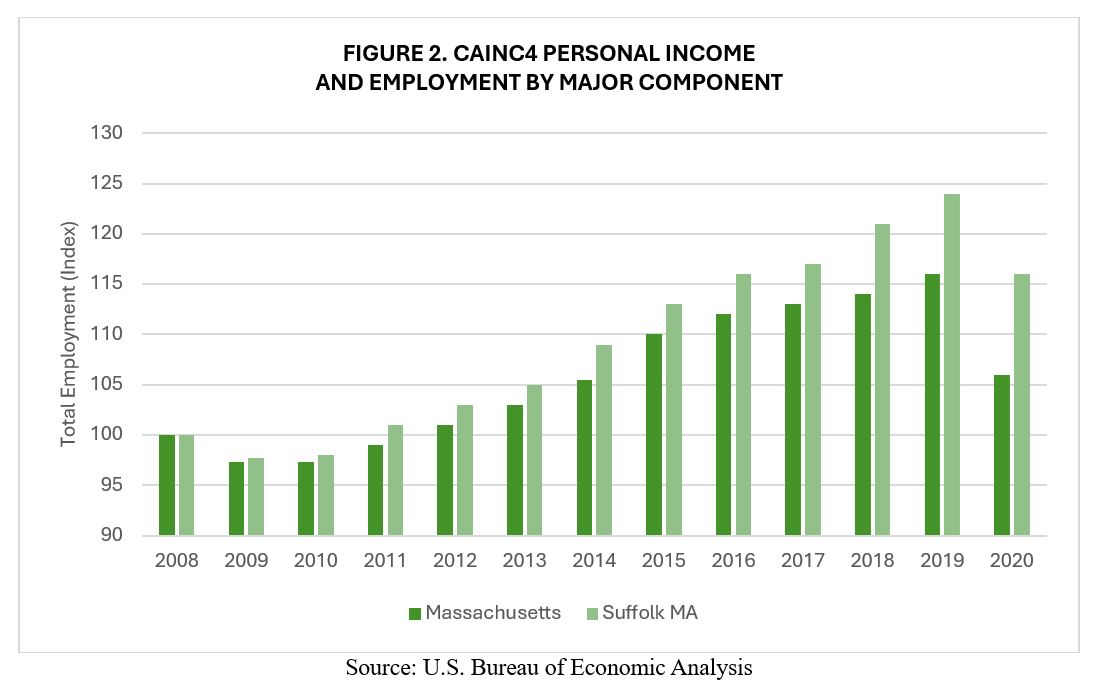

The district that represented the re-imagined urban areas was Seaport-South Boston Waterfront, located in Suffolk County. The urban revitalization and redevelopment of Boston’s waterfront district began in 2010. Supported by Figure 2 below, Suffolk County has exhibited a consistent and exponential growth in the employment index since its inception. In more recent years, the county has widened its total employment index gap compared to Massachusetts state, indicating the county’s resilience in employment and sustained growth.

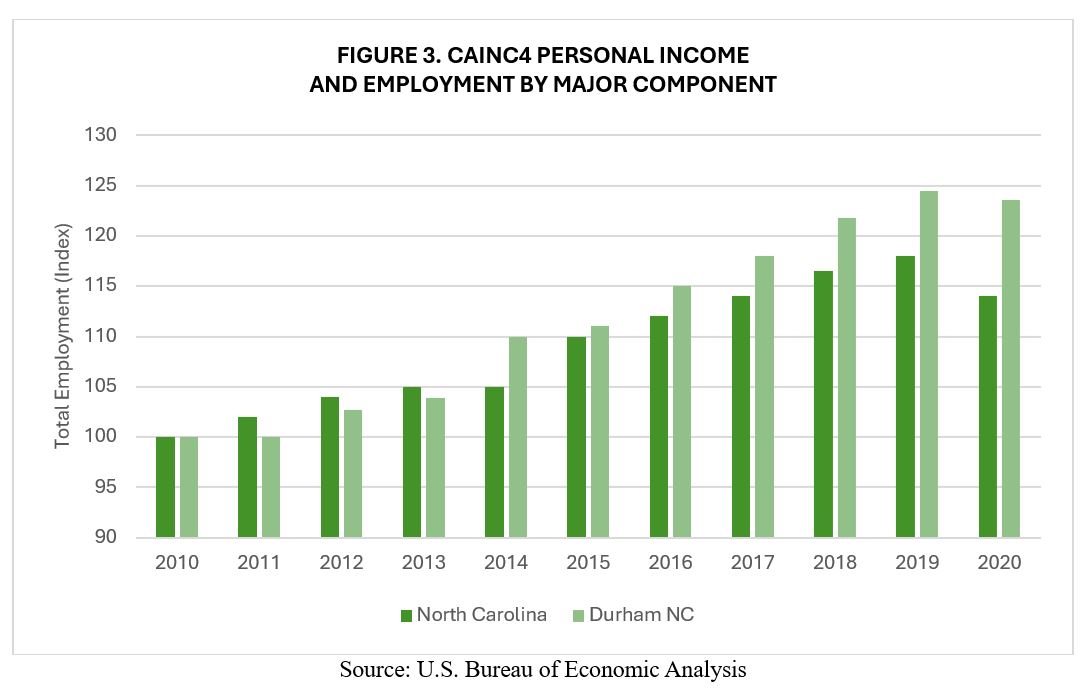

We can also see the impact of Raleigh-Durham’s Research Triangle Park, as representation of the urbanized science park innovation district, to the area. Raleigh-Durham’s Research Triangle Park, established in 1959. The park underwent a significant $50,000,000 redevelopment and master plan revamp in 2015. According to Figure 3 below, Durham County began outperforming the North Carolina state employment index from 2016 onwards. Much like the previous case, Durham County increased its gap with the state, showcasing growth without signs of slowing down.

Based on the three cases discussed above, it’s evident that innovation districts bring a significant positive impact to the local economy, regardless of their type. Therefore, in this article, we aim to delve deeper by not only analyzing the quantitative impact of innovation districts but also exploring the non-quantitative factors that contribute to their success. By doing so, we intend to identify the essential elements that appear in all districts and play a key role in the long-term effort of creating successful innovation districts.

Key Elements of Successful Innovation Districts

As previously mentioned, the primary objective of an innovation district is to rejuvenate the urban fabric, attract investments, and stimulate innovation, productivity, entrepreneurship, and trade. Consequently, the measure of a district’s success or impact extends beyond quantitative investment returns, encompassing qualitative variables such as community growth, job creation, educational opportunities, university research funding, and more. This article aims to measure the success of the district qualitatively to identify the key elements that are important for carrying out this type of long-term strategic effort.

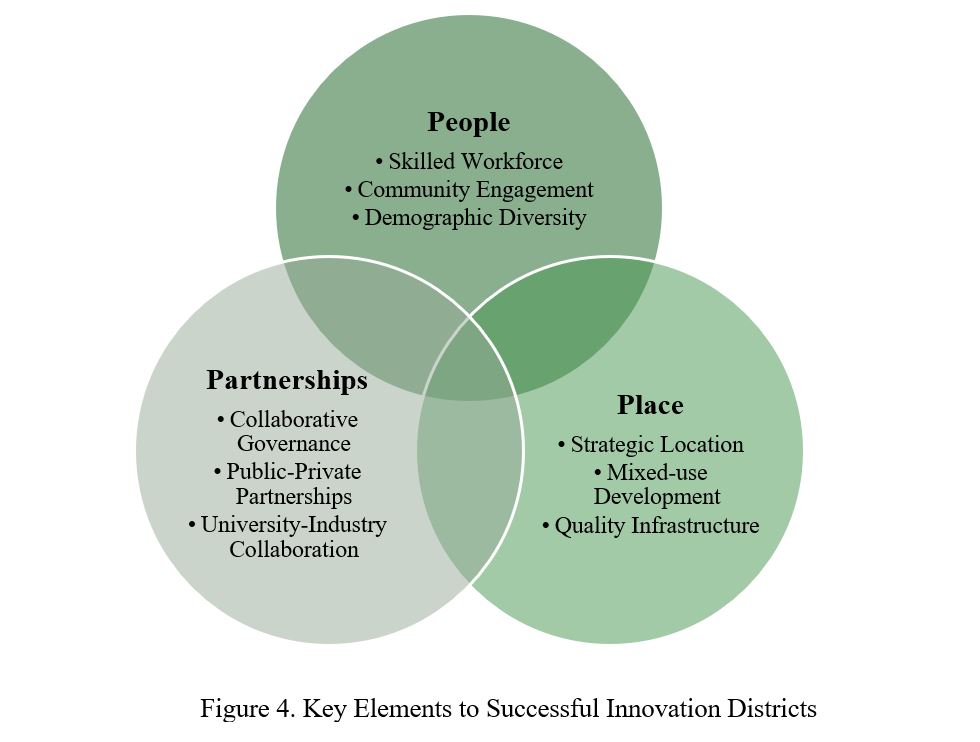

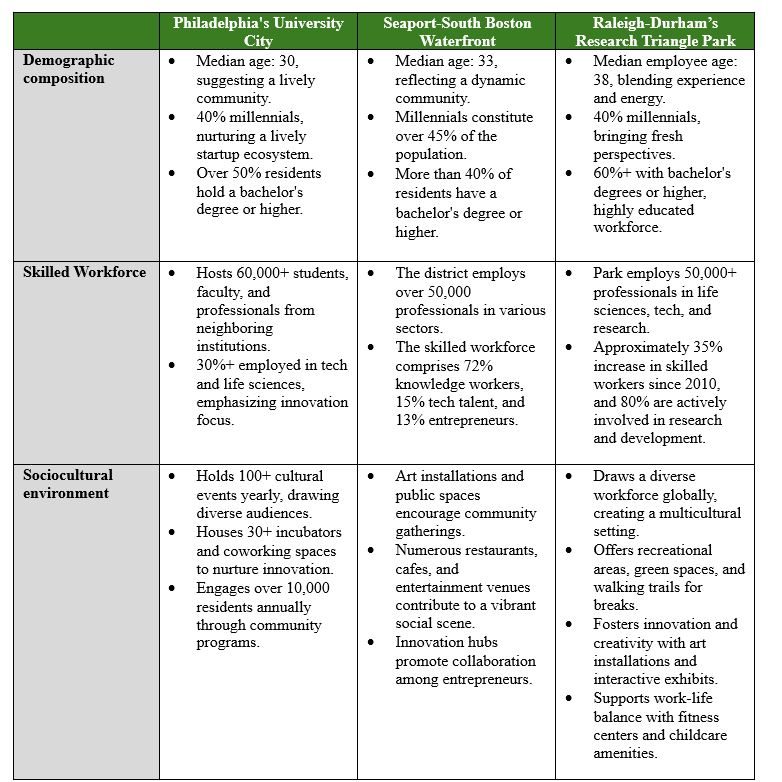

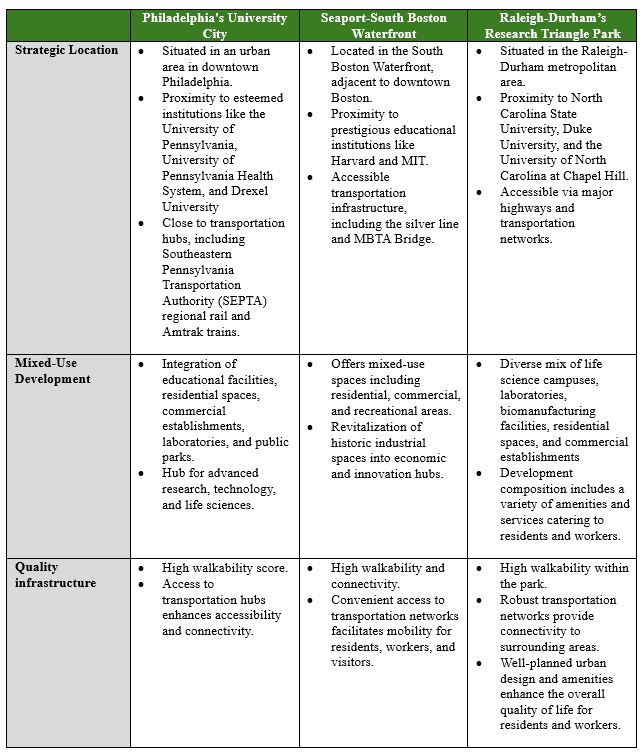

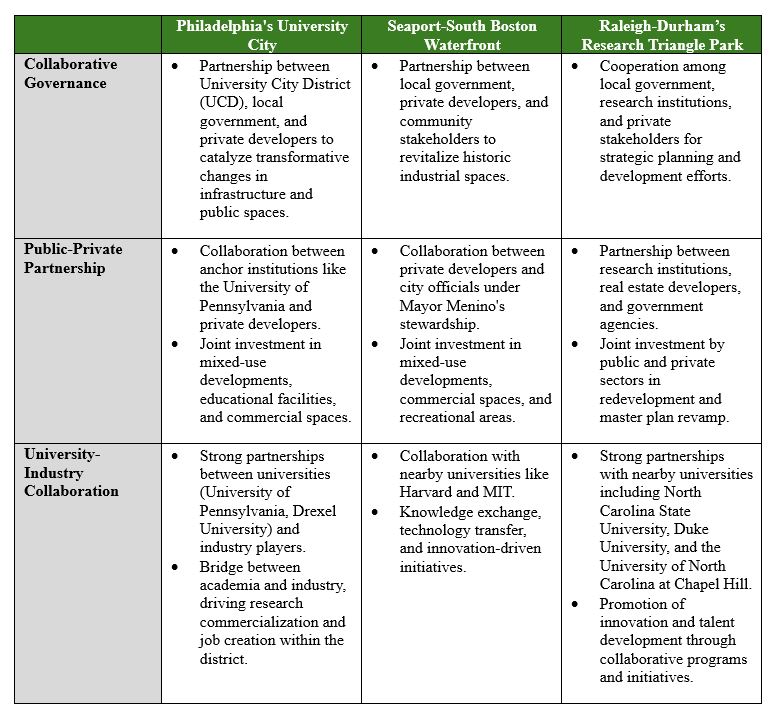

Having explored the unique characteristics of anchor plus, re-imagined urban areas, and urbanized science parks through the lenses of Philadelphia’s University City, Seaport-South Boston Waterfront, and Raleigh-Durham’s Research Triangle Park, it becomes evident that certain commonalities emerge across all three types of innovation districts. At their core, these innovation ecosystems are driven by three key elements: People, Place, and Partnerships.

In each of these innovation districts, the importance of People is underscored by the presence of diverse demographic compositions, skilled workforce, and a vibrant sociocultural environment. Whether it’s the knowledge workers and tech talent flocking to University City, the entrepreneurs and researchers shaping the landscape of Seaport-South Boston Waterfront, or the innovative minds driving Research Triangle Park forward, a thriving innovation district attracts and nurtures a diverse array of talent, fueling innovation and economic growth.

Place plays a defining role in shaping the identity and success of an innovation district. Whether situated in urban cores, historic waterfronts, or suburban enclaves, the strategic location of these districts enhances accessibility, fosters collaboration, and promotes creativity. From the mixed-use developments and public parks of University City to the revitalized industrial spaces and recreational areas of Seaport-South Boston Waterfront, and the compact, walkable neighborhoods of Research Triangle Park, each district leverages the quality of its infrastructure to create dynamic ecosystems where people can live, work, and play.

Partnerships serve as the backbone of innovation districts, driving collaborative governance, public-private partnerships, and university-industry collaborations. Whether it’s the collaborative efforts between anchor institutions and private developers in University City, the public-private initiatives spearheaded by local government and businesses in Seaport-South Boston Waterfront, or the university-industry partnerships fueling research and innovation in Research Triangle Park, effective partnerships are essential for aligning interests, pooling resources, and driving collective action towards shared goals.

From the analysis of the three case studies provided, it becomes apparent that while innovation districts share key feature similarities, the development aspects of these models vary significantly. Consequently, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Developers aspiring to create successful innovation districts must ensure sufficient local demand and a drive for innovation. A collective vision among leaders from city governments, industries, and local universities is crucial for collaborative design, planning, and governance. Support from these leaders is imperative for establishing innovation districts and leveraging the city or region’s existing strengths and differentiating factors, such as neighborhood identity.

In many cases, universities play a crucial role in driving innovation. Establishing a strong relationship with a university is therefore imperative. Collaboration between universities and industries has proven mutually beneficial, fostering a symbiotic relationship that accelerates research and innovation. Innovation districts attract research university students and researchers due to their mixed-use components and live-learn-work-play environment, providing industries with a valuable talent resource pool.

Effectively leveraging the innovation district model also requires a focus on placemaking. Placemaking initiatives attract and retain talent while fostering networks between industries and universities, creating a culture of innovation through inclusive and flexible spaces that allow people to capitalize on the benefits of agglomeration, inter-industry networks, and knowledge spillover. This is particularly important after the COVID-19 pandemic, as many individuals have shifted to remote work, creating pressure on office occupancy. Encouraging workers to return to the office through promoting the benefits of agglomeration and fostering knowledge exchange can revitalize the struggling office sector, supporting related retail services, and overall commercial real estate growth.

Conclusion

Innovation districts have emerged as transformative urban models in the 21st century, offering substantial economic and social benefits. Their success hinges on prioritizing People, Places, and Partnerships as essential elements. By fostering inclusive environments, dynamic urban spaces, and strong collaborations, innovation districts not only drive innovation, economic growth, and community well-being but also attract investments, industries, and skilled workers. This approach creates thriving ecosystems that contribute to the city’s productivity and serve as attractive hubs for real estate development. Collaborating with universities further accelerates research and innovation, while placemaking plays crucial roles in talent retention and network building, ultimately ensuring the long-term success and sustainability of innovation districts in urban development.

Resources

Andrews, J. (2019, June 17). What makes a successful innovation district? Cities Today. Retrieved March 27, 2022, from https://cities- today.com/what-makes-a-successful-innovation-district/

Boston Planning & Development Agency Research Division. (2019, March). South Boston Waterfront Economic Data. Boston Planning & Development Agency. http://www.bostonplans.org/ getattachment/178e7bd7-9770-4c89-98fb-7c3373d4c712

Bracken, D. (2010, September 4). RTP begins updating its master plan- Local/State – NewsObserver.com. News Observer. Retrieved April 12, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20101012050104/http:// www.newsobserver.com/2010/09/04/663597/rtp-begins-updating-rules.

Burke, C., & Zettler, Z. (2022, April 4). Retooling Innovation Districts for Midsized Cities. Urban Land Magazine. Retrieved May 3, 2022, from https://urbanland.uli.org/economy-markets-trends/retooling-innovation-districts-for-mid-sized-cities/?msclkid=f054a719cf1911eca 5972a180181a866.

ECPA Urban Planning. (n.d.). Case Study: The Boston Waterfront Innovation District | Smart Cities Dive. Smartcitiesdive. Retrieved March 27, 2022, from https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/ sustainablecitiescollective/case-study-boston-waterfront-innovation- district/27649/

Heaphy, L., & Wiig, A. (2020). The 21st century corporate town: The politics of planning innovation districts. Telematics and Informatics, 54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2020.101459

Idris, D. (2022). Innovation District Models: Examining The 21st Century Innovation Labs. Real Estate Review, 55. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/communities/17e2ab86-dec8-47c1-9853-314d7dd4f203

Katz, B., & Wagner, J. (2018, October 24). The Rise of Innovation Districts. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/essay/rise-of– innovation-districts/

KPF. (n.d.). Seaport Square Innovation District by Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF). Retrieved March 22, 2022, from https://www.kpf.com/projects/ seaport-square

Research Triangle Park. (n.d.). Research Triangle Park – Our Community. Retrieved March 27, 2022, from https://www.rtp.org/ our-community/

Saunders, P. (2017, July 20). Innovation Districts — Where Talent, Institutions, And Networks Come Together. Forbes. Retrieved February 14, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/ petesaunders1/2017/07/20/innovation-districts-where-talent-institutions- and-networks-come-together/?sh=76e69dfd4099

Seaport District. (2021, December 17). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia. org/wiki/Seaport_District

The Brookings Institution. Retrieved March 29, 2022, from https://www.brookings. edu/blog/metropolitan-revolution/2017/07/11/does-innovation-equal- gentrification/

The Brookings Institution. (2017, May). Connect to Compete: How the University City-Center City innovation district can help Philadelphia excel globally and serve locally. https://www.brookings.edu/wp- content/uploads/2017/05/csi_20170511_philadelphia_innovationdistrict_ report1.pdf

University City District 2017 Annual Review. (2018, January). University City District. https://www.universitycity.org/sites/default/files/ documents/UCD%20Annual%20Review%202017.pdf

University City District. (2022, January). The State of University City 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2022, https://www.universitycity.org/sites/ default/files/documents/The%20State%20of%20University%20City%20 2022.pdf

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “CAINC4 Personal Income and Employment by Major Component,”. Retrieved April 14, 2022, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=70&step=1&acrdn=6.

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. (2022, January 27). University City, Philadelphia. Wikipedia. Retrieved March 25, 2022, from https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_City,_Philadelphia

Yigitcanlar, T., Adu-McVie, R., & Erol, I. (2020). How can contemporary innovation districts be classified? A systematic review of the literature. Land Use Policy, 95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. landusepol.2020.104595

@jamesteohart/Shutterstock.com

@jamesteohart/Shutterstock.com