Many of us make our living preparing forecasts of supply and demand, income and expenses, and the anticipated actions of buyers, sellers, lenders and government agencies. Some years ago, during a presentation of ten years of projected cash flows to a client, my colleague and mentor, announced “The only thing we know for certain about our forecast is that every number is wrong. Neither revenues nor expenses are going to change at exactly the projected rate over the next decade.” After getting over my initial shock, I realized he was right.

So, while the Stanford symposium was enormously insightful, and certainly many of the topics discussed have already and will certainly continue to come to fruition (Airbnb and driverless cars are just two notable examples), what can possibly go wrong along the way?

Political Risk Is an Obstacle to Global Growth

In Congo, the president recently announced plans to run for a new seven-year term despite it being against the constitution. The president of Côte d’Ivoire lost the election in 2010 but refused to leave office. Political risk was once confined to exotic emerging markets including military coups in Fiji in 2000; Thailand (2005 and 2014); and Mali (2012). Electoral fraud has been documented in Kenya (2007) Georgia (2008); Burundi (2010); and Ukraine (2012). More recently we witnessed an attempted military coup in Turkey; a debt default by Venezuela; and increased political sanctions in Russia. And even in the world’s most established markets, investors are still trying to understand the implications of Brexit for the economies of the United Kingdom and European Union.

Should we conclude that Uber, the world’s most valuable startup, with a valuation of about $70 billion and a presence in more than 400 cities around the globe, was unprofitable in China — population 1.4 billion — including more than 150 cities with populations over one million, eventually selling its operation there to local rival Didi, because it did not know how to manage its software business?[1] Or could it be that it did not fully take account of China’s less tolerant political system; civil (based on rules) rather than common law (subject to judicial interpretation) legal system; and vexing regulations, to say nothing of a culture that stresses societal order over entrepreneurism?

When companies expand globally, they face unfamiliar cultural, political and economic environments that put additional, unforeseen pressures on their usual business models. They also face local competitors that understand the local environment far better than they do. Unless they are able to accurately assess and adapt to the culture of the city they are expanding into, they risk becoming the next Nokia or BlackBerry.

Corruption is Rampant in Many Cities Throughout the World

I used to be uncomfortable saying this, but it’s simply become too common and too large of a problem to ignore. I’ve personally experienced having to pay for information that should have been available for free in Latin America, Asia and especially Africa where it’s virtually an everyday occurrence to have your car stopped by soldiers with rifles manning roadblocks saying, “What do you have for me?” or “How can you appreciate me?”,[2] to say nothing of being charged an extra fee at customs outposts. Learning how to deal with bribery when it’s a fact of everyday life is another obstacle to the growth of cities.

If more residents paid taxes, some of this money might be directed to needed new roads and airports. But simply directing this money to government coffers is insufficient. A former national security adviser in Nigeria is alleged to have awarded $2 billion in fake contracts. Nigeria’s state-owned oil company reported that about $1 billion per month disappeared during 2013. In Brazil, the figure in the Petrobras scheme is $17 billion in asset and corruption charges, and in the Philippines the losses from 1MDB scheme are approaching $4 billion.

In India, Kingfisher Airlines filed for “bankruptcy” but all of its books and records have mysteriously vanished. In Brazil, corruption is so rampant that malufar is a commonly-used verb meaning to divert government funds for personal use. In Lagos, private schools teach courses in credit card fraud. In Venezuela, both Proctor & Gamble and Clorox have had factories seized and employees arrested.

The enhanced ability to get clear title to real property would spur investment. Throughout African cities, numerous homes have hand-painted signs on their border walls proclaiming “This house is not for sale” to combat unscrupulous “sellers” of property that they don’t own.

The same issue that recently forced the resignation of the CEO of Wells Fargo, opening up accounts for customers without their consent, is similar to the 2014 Prime Minister’s People’s Wealth Scheme in India, whereby hundreds of millions of bank accounts were opened by branch managers so that the government could boast it was bringing banking to the poor.

Unfortunately, as it turns out, most of these accounts were seeded with only a single rupee, or less than two U.S. cents. Good relations with the government bureaucracy are a requirement for business success in corrupt markets.

Fortunately, many companies are now taking steps in the right direction. The crackdown against conspicuous consumption in China is widely perceived to have had a negative impact on the sale of luxury watches. In South Korea, screensavers on some company computers have regulatory pop-up quizzes that remain on the screen until the correct answer is proffered by the employee. And in some cities, corporate credit cards are now programmed to deny payment to questionable nightclubs and hotels.

Many Global Cities are Not as Advanced as the United States

One of the overriding themes of the Stanford Symposium was “smart cities.” In many of the 35 OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, credit bureaus enable prospective lenders to assess the risk of potential borrowers. But only about ten percent of Africa’s 1.2 billion residents and South Asia’s 1.7 billion population are covered by private credit rating bureaus. The result is that banks lend to government agencies instead of homeowners since it’s easier than dealing with property title issues, while individual borrowers are charged interest rates of 20 percent or more. Clearly the inability to access credit is an obstacle to future growth. By way of an additional example, there are about 175 “unicorns” in the world (private tech companies valued at $1 billion or more), yet only one is in Africa (Africa Internet Group).

In some cities, the lack of credible financial information has given rise to the growth of psychometrics, the science of measuring mental capacities and processes. By developing character quizzes, the U.S.-based Entrepreneurial Finance Lab (“EFL”) has processed some 300,000 applications for credit from individuals.

In a similar vein, the lack of infrastructure in many emerging cities has been an obstacle to the growth of cities. Manhattan is about one-third roads while some parts of Africa are five percent roads. As a result, it’s more expensive to ship goods 500 miles from Lagos to Kano than 7,000 miles to Beijing.

One possible outcome is that just as Africans have gone from “no phones to smart phones,” Africa may evolve from a dearth of highways and trucks to delivery by drones. Access to self-driving cars is among Africans’ least concerns.

Conclusion

Despite these obstacles, many companies and institutions have been successful in building their brands globally. Reinforcing Stanford University as the ideal choice for the Global Cities in an Era of Change symposium, it is fitting that most of the world’s most valuable brands have come from companies in technology-related categories.

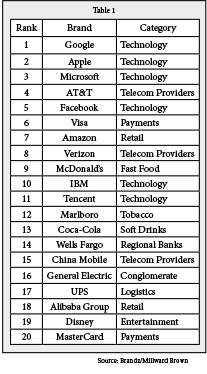

Brandz recently issued its annual ranking of the Top 100 Most Valuable Global Brands. In 2016 these were (see table).

Brandz recently issued its annual ranking of the Top 100 Most Valuable Global Brands. In 2016 these were (see table).

For clues as to which global cities are best poised for growth, it’s worth noting that 17 of the 20 companies on the Brandz3 list are based in the United States (although that’s not necessarily where they get most of their sales; Coca-Cola gets more than 80 percent of its volume overseas) with the remaining three (Tencent, China Mobile and Alibaba Group) headquartered in China.

Yes, many of the Stanford symposium forecasts will come true, and those of us who attended and our clients will be the wiser for it. But the road to change may be rockier and the destination different than anticipated.

Participants at the symposium were well-advised to absorb as much as possible, yet reach their own conclusions. As Henry Ford is reported to have said: “If I had listened to my customers, I would have given them a faster horse.”

Endnotes

[1] Uber maintains it is a software company that connects drivers with customers.

[2] The Economist reported that two American economists, Jeremy Foltz and Kweku Opoku-Agyemang, examined 2,100 long-haul truck journeys in Ghana and discovered that the average driver was stopped 16 times to extract money.

[3] Source: BrandZ/Millward Brown