Volume 39, Number 1

Spring 2014

By Nicholas Chatzitsolis, CRE, FRICS, and Prodromos Vlamis, Ph.D.

Introduction

The Greek residential market (and the Greek property market in general) has always been one of the pillars of economic growth in Greece. Since the early 1950s the development industry has been one of the major contributors to and one of the most important sectors of the Greek economy.[1] The construction industry in particular significantly affected the country’s economic growth and because of that, its importance for the growth prospects of the Greek economy has never been questioned. The construction sector’s contribution to the GDP since the year 2000 ranges between six and eight percent in both current and constant prices,[2] while it employs more than seven percent of the total country’s labour force.[3] Also, the construction sector affects heavily, although indirectly, other sectors of the Greek economy such as mining, building material, electrical equipment, etc.[4]

During the first four years of the economic crisis, public investment for development projects was dramatically reduced. To illustrate this point further, focusing on the construction industry in particular, according to the Hellenic Statistical Authority, a steady annual decline of more than eight percent since 2006 has been registered every year in terms of building permits issued. Thus, the crisis that the Greek residential market is currently facing can mainly be attributed to the current fiscal stance of the Greek economy.[5] The 2008 crisis in the United States subprime loans market and the increase in oil prices are still affecting liquidity in markets, the cost of capital, economic growth and capital markets at large. This negative economic environment affects the European Union countries and Greece, too. Economic repercussions of the crisis cannot be entirely estimated since the crisis is ongoing.

The Greek housing market may be characterized as imperfect and opaque. Though the commercial market has gone through a phase of regulation during the late 1990s and the early years of the 21st century, the residential market still retains all its peculiarities and is seen by the average Greek as the “peoples’ investment market.” Regardless of various fiscal and taxation measures aimed at regulating this market, a number of cultural, social and financial considerations, along with a recent dramatic drop in terms of property values, have prevented its improvement.

The purpose of this article is to present a general overview and a critical discussion of the developments in the Greek residential market and identify and analyse the possible links with all its “peculiarities.” These peculiarities include: 1) the “counter performance” development process, which is unique by global standards; 2) the ill-based concept that every family must own two or three residential units for “security” purposes—and that this type of security was favoured, in light of the high inflation environment of the 70s, 80s and mid 90s, as the best type of inflation hedge investment by virtually all different income classes of Greek households; 3) the extensive land fragmentation[6] in Greece; 4) the high rate of owner occupation; and, 5) the trend to concentrate residential development in virtually two cities (Athens and Thessaloniki).

Our analysis indicates that the above considerations result from a number of socioeconomic problems that are hard to resolve. This fact along with lack of demand for the acquisition of new homes makes developers more conscious and selective when measuring their risk. Residential real estate experts now state that recovery of the housing market may take up to eight years in order to reach 2007–2008 levels. Recovery, however, depends on property taxes—namely capital transfer tax and capital gains tax.

This article presents data regarding the recession in the Greek housing market, a number of considerations under assessment as well as their impact on the residential market, and the authors’ conclusions.

The Greek Housing Market and the Current Crisis

The latest available data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority7 reveals that the Greek economy is still in recession, with the growth rate of GDP being -2.6 percent (measured in fixed prices, base year 2005) in 2013Q4 (in comparison to 2012Q4). This recession is reinforced by the existing negative psychology—crisis of confidence— because the market participants are afraid of the not-yet-seen repercussions of the Greek debt crisis. Moreover, frequent changes to tax laws create uncertainty and reduce business confidence.[8] This is expected to negatively affect property transactions and, consequently, the companies engaged in the Greek construction sector, real estate services, etc. Also, the so-called “objective values”[9] of real assets for both urban and rural areas are to be reviewed upwards—sometime between now and 2016—because they are unchanged since the year 2007. This might have a further negative effect on property transactions.

Volume of Residential Property Transactions

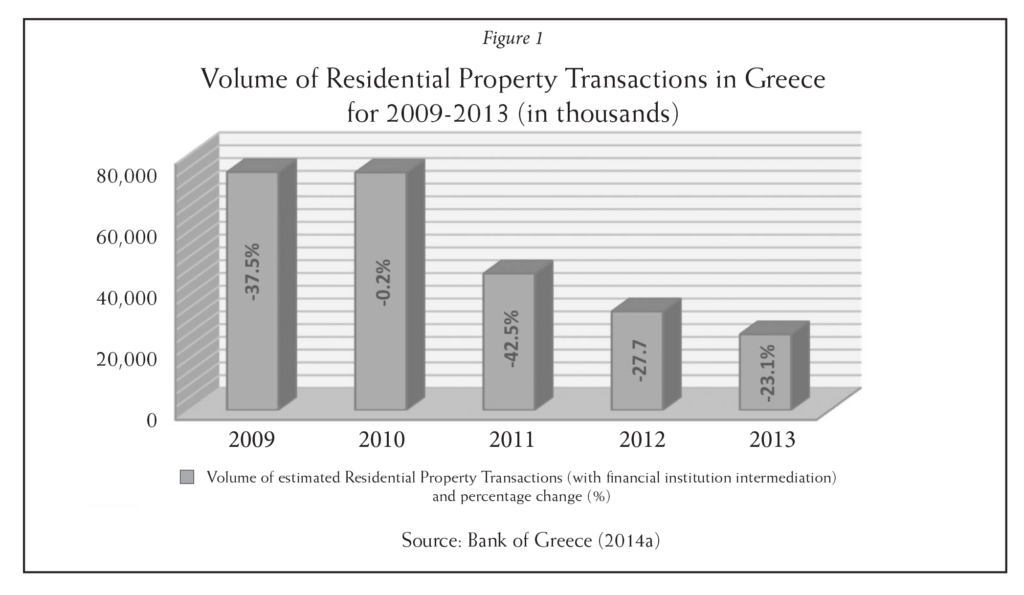

Data recently published by the (Central) Bank of Greece[10] show that the number of real estate transactions continues to fall, from 74,586 in 2009 to 74,457 in 2010; 42,814 in 2011; 30,964 in 2012 and 23,801 in 2013 (Figure 1).

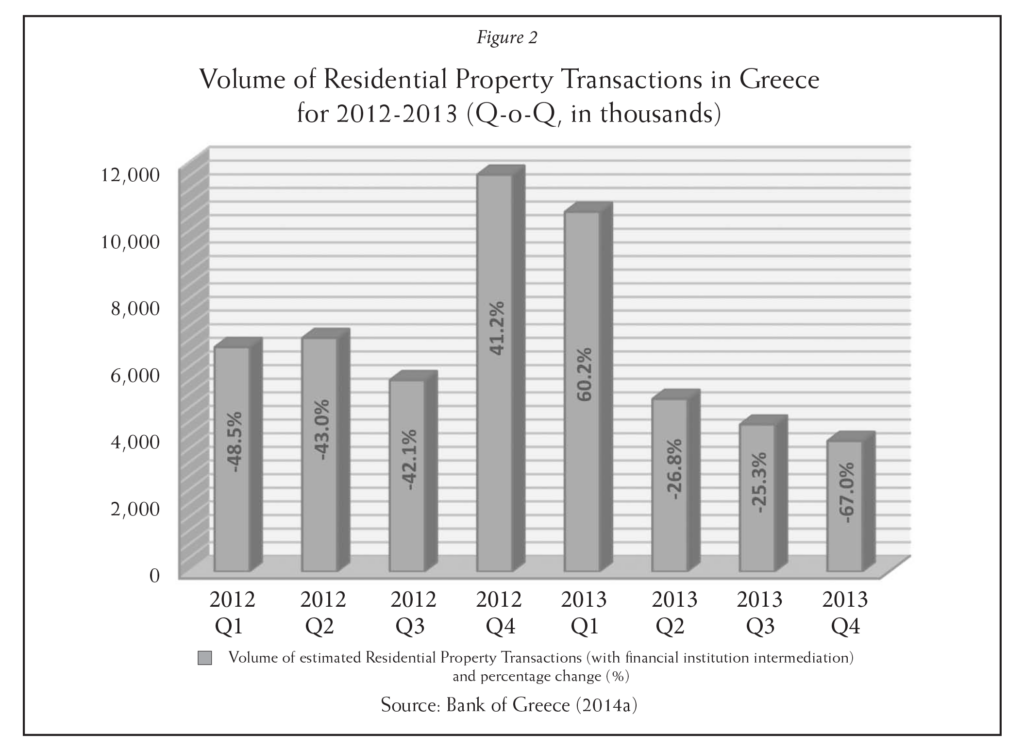

The Quarter-on-Quarter (QOQ) picture for the volume of the residential property transactions for 2012 and 2013 shows that property sales continue to fall, from 5,074 in 2013Q2 to 4,321 in 2013Q3, and 3,841 in 2013Q4 (Figure 2).

Building Activity

The latest available data published by the Hellenic Statistical Authority11 reveals that the volume of the overall (private and public) building activity across the country (measured by the number of building permits, both residential and commercial)12 has decreased by 27.4 percent during the period January – November 2013 (in comparison with the period January – November 2012). As well, recently published data by the Hellenic Statistical Authority[13] reveals that the production index in construction has fallen by 8.3 percent in 2013Q3 (in comparison with 2012Q3).

Bank Credit for the Domestic Private Sector: Residential Mortgages

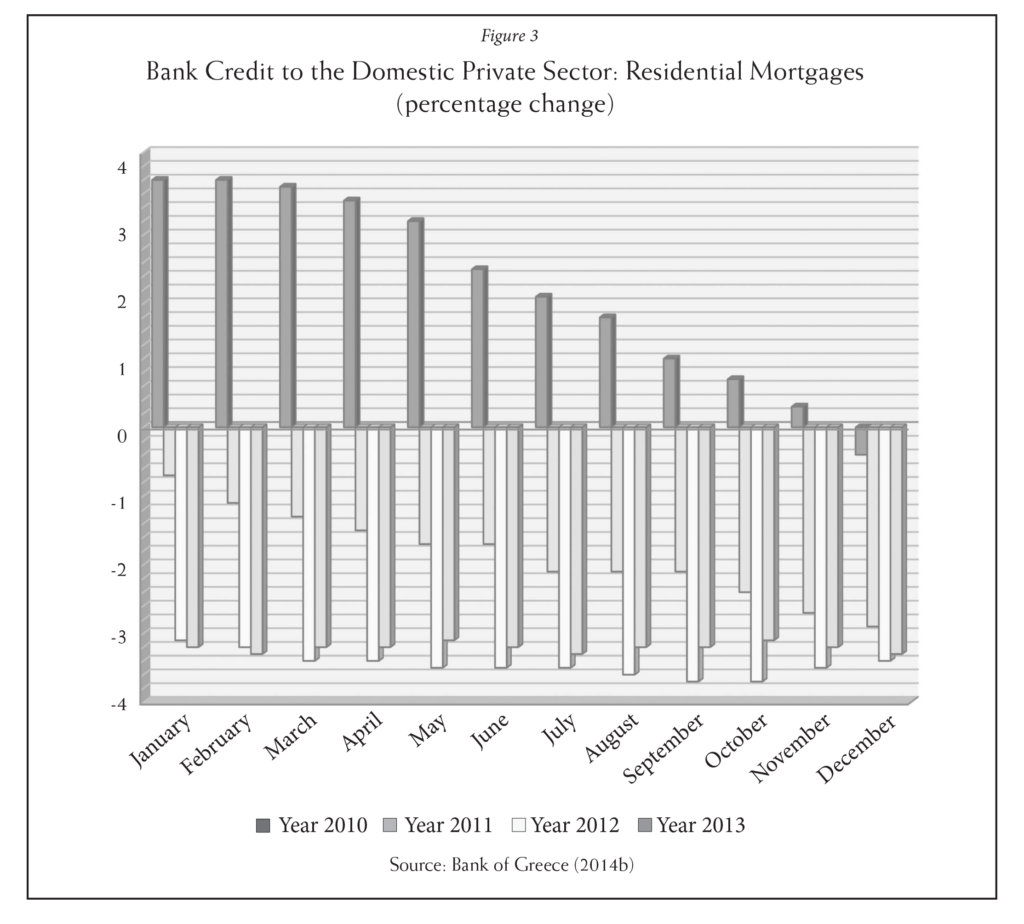

The crisis that the Greek property market is experiencing also has been crucially linked to the Greek banking crisis and the consequent credit crunch that has emerged; commercial banks are facing liquidity constraints and thus, since December 2010, they keep reducing the available funds to the domestic private sector[14] (Figure 3).

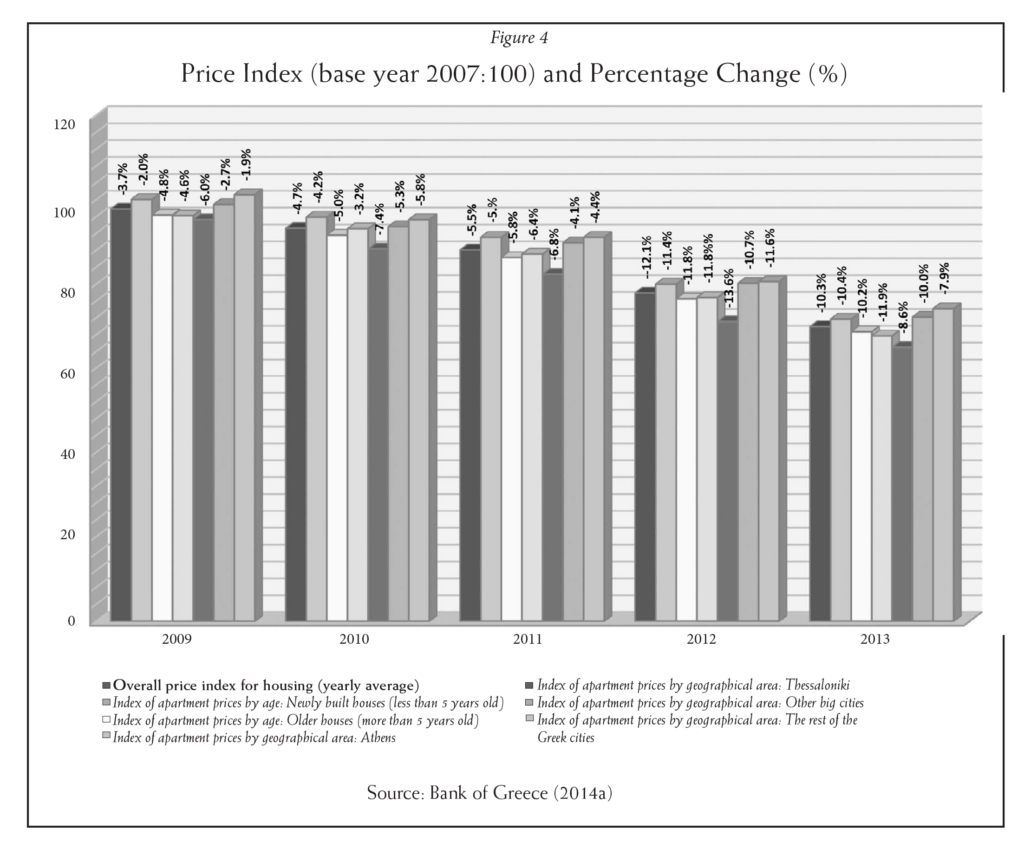

A rather frequent and common topic in Greek newspapers is real estate investment. When papers and journalists refer to real estate investment and property prices, it takes only a bit of reading to understand that they refer exclusively to the residential property market. And thus, when they refer to property values, these are in fact prices of apartments, maisonettes and houses. Surprising as it may sound, for the average Greek, a home has always been an “investment” that will supposedly grow year after year and will predetermine the financial security of the younger members of the family. As a result, many middle-class Greeks invested most of their earnings and savings in a second home, and/or in an additional apartment for rental income, and maybe a third or a fourth residential property or small retail unit. Or so was the situation until 2008 when all this ideal world of property price growth collapsed. After more than fifty years of relying upon real estate as an investment, middle-class Greek households had to face the rapidly deteriorating house prices that today stand at approximately 36 percent of what they were in 2008 (see Figure 4).

The owner occupier sector in Greece, as far as the residential market is concerned, is very strong and is considered to be the one of the highest in the European Union. As of 2009, the home ownership rate in Greece was estimated to be around 80 percent.[15] Furthermore, middle and upper middle income groups enjoy second homes situated in their home town/village, many acquired in the booming decades of the 1980s, 90s and the early years of this century.

Apart from the social, cultural and financial security considerations, another factor that has boosted the owner occupier sector is the high building development coefficient in most urban communities. The introduction of high density building regulations in conjunction with relatively cheap land may have contributed to satisfying housing needs, but had a detrimental effect on the aesthetics of cities and towns, as well as on internal migration and balance of population at the national level. Young people in the 1950s, 60s and 70s migrated to Athens, Thessaloniki and other big towns to find jobs, thus abandoning rural areas and the regions. The responsibility of the Greek political system at large is an important element here as it seems that the Greek political establishment has never aimed at a balanced development between rural and urban Greek regions. They preferred to offer rural citizens promising jobs and a prosperous urban life through appointments to a central government department or the broader civil sector.

The destruction of the Greek architectural heritage of the late 19th and 20th centuries through mass demolitions of neoclassical buildings as well as traditional buildings of the 1960s and 70s, to be replaced by ugly multi-story structures, resulted in the creation of densely populated neighbourhoods, with no local identity, no aesthetics, no green space, no parking facilities, thus resulting in a poor quality of life. In the view of the Greek political establishment, the transformation of low density urban communities—characterized in the past by beautiful traditional buildings and open spaces—into densely populated neighbourhoods was seen as progress and full accomplishment of housing needs. If we may say so, this proved to be a very short-sighted approach.

Government authorities turned blind eyes to illegal structures, extensions and additions to buildings, all of which bloated the owner occupier sector. This resulted in almost doubling the useable floor areas, mainly in detached or semi-detached houses and maisonettes. In many cases, a surveyor measuring a building quite often finds no compatibility between actual floor space and title deed content. City planning authorities have become stricter and tougher recently but find it impossible to demolish illegal structures without then facing acute social problems. Accordingly, authorities try to resolve such issues through penalty payment enforcement measures. However, since mass breach of law has taken place, it is difficult to secure settlement of fines. It may take years until these illegal construction problems are fully resolved.

Other factors contributed to the transformation of low density urban communities into problematic urban agglomerations: 1) low land values, which made it easy for developers to build apartment blocks; and, 2) the introduction of quite an innovative form of development known as the system of “counter performance.” According to this system, a site owner assigns his/her land to a developer, and once building construction is completed, the owner receives in exchange a proportion of the newly completed structure. The proportion varies and depends on the building coefficient, the quality of the area and on the state of supply and demand for readily available accommodation.

It should be noted that at least five years preceding the crisis, as a result of continuously rising demand and increasing housing prices, developers could no longer acquire land cheaply. Once the crisis started, the effect was detrimental; they were left with empty apartments and houses, which today exceed 200,000, almost half of the total vacant housing stock (this figure may be low by American standards but should be considered in the context of the population of Greece, which does not exceed 11 million people). Most developers—usually small local firms—acquired expensive land and paid high construction costs aiming for high specification buildings that reflected high selling prices. When the recession hit, nobody could afford to pay a high price for an apartment or a house. There was simply no market for residential units that would sell at 2007–2008 price levels.[16] With so much development originally concentrated in the central cities of Athens and Thessaloniki, and still so many of these homes vacant—upwards of 200,000 units—it does not make sense to try to develop new housing in outlying areas.

A significant fact in post-crisis Greece is that regardless of the 400,000 empty residential properties (200,000 newly built units plus 200,000 older homes), the country is faced with a huge number of homeless persons. Even in the post-Second World War era of the 1940s and 1950s, this phenomenon was unknown in contemporary Greece. Greeks used to bitterly criticize homeless Parisians, Londoners and New Yorkers who sleep in the streets or in the subway waiting areas. Nowadays, the increasing number of homeless can be seen virtually everywhere in the large Greek cities. It is a relatively recent development (starting only five years ago) reflecting the results of the fiscal crisis.

The low quality urban residential environment in conjunction with lack of social housing and social services has had a detrimental effect on the quality of living of the average Greek citizen. This is certainly more acute in Athens and the major urban centers. We propose a number of solutions that could, in our view, help solve some of the housing problems that currently exist in Greece:

1. Housing for the homeless. The higher proportion of homeless is among the indigenous Greek population and the unemployed immigrants, most of whom are living in the country illegally. The government owns several abandoned public buildings, former army camps, etc., that could be utilised for this purpose. Furthermore, regardless of the situation in the economy, there are some funds that could be allocated for renovation, construction and property management.

2. Government subsidies for low income tenants with high personal debt. The irony is that most of them are forced to pay enormous taxes to the state with virtually no return benefits. In Greece there is a graduated income tax system based on the amount earned. There are, however, heavy taxes on property, on “luxurious living,” on car possession (for vehicles over 2,000cc) and on car use, as well as a levy for all self-employed professionals that has to be paid regardless of earnings. It is undoubtedly an unfair system and has been subject to severe criticism.

3. Improved environment in most urban centers, mainly in Athens and Thessaloniki. Improving blighted inner city areas should help generate local and international tourism; consequently raising retail rental values along with interest in investment and the provision of services. Investment in such urban and social infrastructure will pay back benefits: increase overall consumer and commercial demand, stimulate the frozen property market and certainly attract investment from both home and abroad.

4. Rationalize taxation of property ownership and take special care of first-time home buyers. Paying enormous taxes to the state just because someone has inherited an apartment or a house has no rationale. In most developed countries, ownership taxes go to local governments and are used for the improvement of the urban environment, for services provided to local residents and for the maintenance of neighbourhoods. In Greece, most ownership taxes go directly to the central government and no one understands whether good use is made of the funds. Moreover, the unbelievable and unprecedented continuous change in terms of legislation can confuse even the most experienced tax expert who has good knowledge of government legislation.[17] A permanent and rational taxation system, friendly to homeowners, potential buyers and investors, and accepted by all economic groups of society will only bring benefits to the government and investors alike. In light of this, the Greek government has recently announced a series of measures aiming to attract foreign direct investments. These measures include an ambitious privatisation plan aiming to generate employment, simplified procedures for the establishment of firms and enterprises, provide resident permits for foreigners outside the EU who acquire expensive property, and tax relief for international investors. The response from the market so far has not been that enthusiastic since the taxation situation is rather obscure at the moment, and it may take time until the potential benefits of the announced measures are realized.

Concluding Comments

The implementation of strict austerity programmes, designed by the Greek government to reduce the budget deficit and stabilize public debt, caused a substantial decrease in demand for goods and services, pushing the Greek economy and consequently the property market into deep recession.[18] The severe crisis the Greek property market is currently facing is reflected in a deteriorating volume of residential property transactions; a low volume of overall (private and public) building activity across the country; reduced bank credit availability for the domestic private sector (residential mortgages); and eventually the considerably lower prices for housing. In this article, we also identified and critically discussed possible links between the recent developments in the Greek residential market and its peculiarities, such as the counter performance development process; the ill-based concept that every family must own two or three residential units for security purposes; the extensive land fragmentation in Greece; the high rate of owner occupation; and the concentration of residential development in two urban areas (Athens and Thessaloniki).

The possibility of the Greek residential market’s coming out of the recession is crucially linked to market participants’ expectations, improvement of the lending terms of construction companies, and the recovery of the economy at large. Th is is the case because the factors that contributed to the exemplary growth performance of the Greek property sector in Greece, particularly after the year 2000 (ample funding for public infrastructure; implementation of stabilizing macroeconomic rules and policies that led to low-cost financing; the organization of the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, which significantly boosted investment activity; and the inclusion of new land in the National City Plan, which expanded the available space for new construction) have now ceased to exist.[19]

Finally, we offered a number of useful policy proposals regarding the steps Greek policymakers should take in order to achieve the necessary property tax system reform. If such reform is implemented, a friendly environment for potential investors in the Greek real estate market will be created and fast, customized, investor friendly solutions for development projects on the residential market will become available. Eventually, hopefully, all of the above will contribute to the restarting of the Greek economy and fuel economic growth.

Acknowledgements

Part of this article was completed while Prodromos Vlamis was a visiting fellow at the Hellenic Observatory, London School of Economics and Political Science, during the academic year 2011–2012. The paper has greatly benefited from the constructive suggestions of Vassilis Monastiriotis. The authors would like to thank discussants of the paper and conference participants at the 12th Annual Conference of the Hellenic Finance and Accounting Association (University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, December 13–14, 2013, Greece), the ERSAGR 2013 Conference (University of Patras and Hellenic Open University, June 14–15, 2013, Patra, Greece), and seminar participants at the Centre for Planning and Economic Research (March 16, 2011, Athens, Greece), for useful comments and discussions. Authors also wish to thank Nikolaos Philippas and Antonis Rovolis for valuable comments. ■

Endnotes

1. Kalfamanoli, K. and P. Vlamis, “Trends, Prospects and Weaknesses of the Greek Real Estate Market,” (in Greek), Volume of Essays in Honour of the late Professor P. Livas, University of Piraeus Press, Greece, 2010, pp. 61–89.

2. Hellenic Statistical Authority (2012), ‘‘Annual National Accounts: Gross Added Value by Industry (Years 2000–2012),’’ Athens, Greece, available at: http://www.statistics.gr/portal/page/ portal/ESYE/PAGE-themes?p_param=A0702&r_param=SEL12&y_ param=2012_00&mytabs=0 (Accessed 25-02-2014).

3. Hellenic Statistical Authority (2014), ‘‘Labour Force Survey – Third Quarter 2013,’’ (press release in Greek), Athens, Greece.

4. Benos, N., S. Karagiannis and P. Vlamis, “Spatial Effects of the Property Sector Investment on Greek Economic Growth,” Journal of Property Investment and Finance, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2011, pp. 233–50.

5. Vlamis, P., “Greek Fiscal Crisis and Repercussions for the Property Market,” Journal of Property Investment and Finance, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2014, pp. 21–34.

6. The number of owners of estates of substantial size is relatively small. Most land is fragmented into small parcels and a significant proportion of the population is property owners. Lack of a modern land registry, particularly in rural areas, creates disputes between individual land owners on many occasions, while trespassing is not uncommon. In urban centers, on the other hand, condominium principles are not applied in the same manner as in the U.S. In multi-story residential apartments, management and building maintenance is sometimes a difficult task, as some co-owners may not agree between themselves and building management rules cannot, in practice, be applied.

Other associated problems are concerned with public land that, on numerous occasions, has been trespassed on. Many cases of dispute between private individuals and the government are pending in courts for years. As a result of these disputes, on many occasions, the government cannot develop or offer land for sale or lease to investors.

Finally, in cases in which a large development project may take place—on a coastal picturesque site for example—the unification of small parcels becomes an extremely difficult task, as some owners do not agree to sell, while others require exorbitant sums of money in order to sell their properties.

The good news, however, is that a long-term solution can now be seen in the not too distant future, as a new National Land Registry is already underway and has produced, even at this early stage, positive results. The completion of the land registry may take a few years, but once concluded, property management will most certainly become more efficient.

7. Hellenic Statistical Authority (2014), ‘‘Quarterly National Accounts – Fourth Quarter 2013,’’ (press release in Greek), Athens, Greece.

8. Kalfamanoli, K. and P. Vlamis, “The Greek Real Estate Market for the Interested Foreign Investors: Prospects and Problems,” (in Greek), Journal of International Economy and Politics “Agora without Frontiers,” Vol. 13, No. 3, 2008, pp. 194–211.

9. The “objective value” of the real estate assets is, in fact, the “taxable value” of transactions in the Greek real estate market. Sometimes the objective value of a property is lower than its actual market value. To adjust for the difference between the objective value and the market value of a property, the former is frequently reviewed (particularly when Greek governments are short of tax revenues). In most cases, the objective value distorts actual prevailing market conditions and is not substantiated by comparable evidence. Objective values for the different types of real estate assets are exogenously set by the Greek government and their estimations are theoretically based on prevailing market conditions (demand and supply).

10. Bank of Greece, ‘‘Indices of House Prices and Residential Property Transactions–Fourth Quarter 2013,’’ (in Greek), February 14, 2014, Athens, Greece, available at: http://www.bankofgreece.gr/Pages/ en/Bank/News/PressReleases/DispItem.aspx?Item_ID=4520&List_ ID=1af869f3-57fb -4de6-b9ae-bdfd83c66c95&Filter_by=DT (Accessed 25-02-2014).

11. Hellenic Statistical Authority (2014), ‘‘Building Activity [volume] – November 2013 Provisional Data,’’ (press release in Greek), Athens, Greece.

12. It is worth mentioning here that data published by the Hellenic Statistical Authority regarding the volume of the private and public building activity across Greece does not distinguish between residential and commercial building permits. In other words, residential and commercial building permits are both included in one single number and the Hellenic Statistical Authority does not disentangle the two figures.

13. Hellenic Statistical Authority (2014), ‘‘Production Index in Construction – Third Quarter 2013 Provisional Data,’’ (press release in Greek), Athens, Greece.

14. Bank of Greece (2014), “Bank Credit to the Domestic Private Sector: December 2013,” Athens, Greece, available at: http://www.bankofgreece.gr/Pages/en/Bank/News/PressReleases/Di spItem.aspx?Item_ID=4493&List_ID=1af869f3-57fb -4de6-b9ae- bdfd83c66c95&Filter_by=DT (Accessed 25-02-2014).

15. “List of countries by home ownership rate,” Wikipedia, available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_home_ownership_ rate (Accessed 25-02-2014).

16. Most of the Greek construction companies rushed to build new houses before the introduction of VAT on new residential buildings (effective from 01–01–2006). When they completed the construction of the houses in 2006–2007, demand for new houses had already started decelerating. Potential buyers are now looking for older properties (between 2–10 years old) due to lower and far more competitive values rather than buying the more expensive brand new ones. The Greek construction companies appear to be unwilling to start selling at lower prices the stock of newly built houses they own because if they do so, they will realize huge losses. Moreover, the majority of companies in the Greek construction industry are family-owned small- and medium-sized companies, which are not highly leveraged. They mostly use equity capital to finance the construction of new houses (by using the so-called “counter performance” process in the housing development field) and thus, they are sort of immune to interest rate volatility. Finally, most of the Greek construction companies accumulated considerable profits during the boom phase of the business cycle (1994–2007) and now they feel comfortable to follow a “wait-and-see” policy, believing the holding costs of these vacant homes will not exceed the potential loss the construction companies will take. On the one hand, if their assumptions are valid they will continue to hold onto these homes, hoping the market will rebound rapidly. It seems they are willing to wait until that happens. On the other hand, according to the new law the Greek government recently passed (Law 4223/2013), Greek construction companies will have to pay property tax on these units even if they are not occupied and not producing any income. This is something they will have to seriously take into account.

17. Vlamis, P., “Institutional Reform as a Prerequisite for the Exploitation of Public Real Estate Assets,” (in Greek), forthcoming Aeixoros Texts of Urban Planning, Planning and Urban Development Journal, 2014.

18. Kouretas, G. and P. Vlamis, “The Greek Crisis: Causes and Implications,” Panoeconomicus, Vol. 57, Νο. 4, 2010, pp. 391–404.

19. Karousos, E. and P. Vlamis, “The Greek Construction Sector: An Overview of Recent Developments,” Journal of European Real Estate Research, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2008, pp. 254–66.